“Here we have the ground zero cafe,” says Bart Ives, gesturing toward a white frame building standing in the open center courtyard of the Pentagon. “It’s a hot dog stand.” Ives, a boyish forty-seven-year-old environmental protection specialist, flashes me a smile that acknowledges the irony of selling wienies right in the heart of the biggest military complex known to humanity. Trying to be polite in spite of being harried, he tells me he doesn’t know when the snack bar picked up the snappy nom de guerre, “but you can be sure it’s still somebody’s ground zero.”

Sitting in the epicenter of so much power, the cafe looks adamantly innocent and idealistic. It is plain and temporary-looking, as if some military precept dictated that making any design statement beyond the most faceless government-issue variety would be unseemly. The cafe has been there in one form or another since the building was constructed between 1941 and 1943, and the official designation always has been just the generic “center court snack bar.” This austerity reminds me that the military is an order apart from ordinary, profit-driven American life, and the Pentagon is its chief monastery.

It’s 11 A.M on a balmy Friday in September, but no one in the courtyard is standing in line for a hot dog or even a strolling about. Civilians and soldiers in immaculate uniforms hurry along the pathways that crisscross the courtyard, heading toward doorways in the five sides of the inner A ring. The Pentagon still seems to breathe that original air of emergency, that sense of urgent industry in defense against great danger that caused it to be built in the early days of World War II. “I liken it to walking into a hurricane ever day,” says Ives. “It’s a very high-energy place that makes a lot of demands on individuals, and in this era of downsizing it’s even more intense.” For the past four years, Ives, one of the many civilian employees of the Pentagon, has been President of the Pentagon Meditation Club.

We walk the endless bare corridors of the “biggest office building in the world,” pass spools of fiber-optic cable as big as upended cars, and I learn there is enough such cable in the Pentagon to wrap around the Earth fives times. The atmosphere is all business; space is tight. There are pockets of polished-brass dignity like the “Hall of Heroes,” honoring Congressional Medal of Honor winners. Even the most casual observer knows, with the same precision that is the pride of the military, that the real power—like the famous subterranean War Room and all that fiber-optic cable, once it’s wired—is buried, not for show.

When the Pentagon was built, President Roosevelt stipulated that no marble was to be used in the construction. It was not to be a monument to war, not a Reichstag, but a headquarters of defense. Defensiveness—and a feeling of terrible scarcity—pervades the Pentagon like a gas. Connected to vast projects, people fret about downsizing and tough budgetary times. Housing approximately 25,000 workers and operating on a budget this year of close to $253.7 billion, the Pentagon buzzes with the message that they don’t have enough manpower or time or money to do everything that needs to be done to make the world safe.

“Some days,” Ives continues, “I’ll be sitting on the bus to go home and I’ll find that I’m shaking from the adrenaline that kicks in from the stress. I won’t even be aware that it’s happening to me but when I get home I feel like a balloon with all the air let out.”

Meditating at the Pentagon is a way of being sane in the midst of the madness. Approaching the chaplain’s conference room, where the meditation club meets during the noon lunch hour each Friday, Ives explains, “What I’m interested in now is using meditation as a vehicle to get in touch with my soul or my cosmic consciousness. A lot of the pieces of the puzzle would fall into place if we could make that connection with our eternal nature. So I’m trying to use meditation to make that contact or build that bridge.”

One advantage of trying to build that bridge at the Pentagon, according to Ives, is that the group’s private efforts can benefit many others. He calls the meditation club a “pilot light.” Typically drawing more than six people to any one meeting, with another thirty or forty members (military and civilian) on the mailing list, the club’s presence is nonetheless a reminder that another source of strength, even a different order of power, can emerge when we dare to step back from the business of defense and just be.

“It’s very important for people just to know it’s here,” Ives insists. “I get phone calls from across the country and mail from people all over the world who are so heartened by knowing that this organization is here. A Buddhist writer I spoke to called it ‘a lotus in the mouth of the dragon.’ They see it as a vehicle for good, to help shape some of the energies that are here.”

Founded in 1976, the Pentagon Meditation Club claims no one sectarian or religious affiliation. Yet—presumably because of the affiliation between meditation and Asian religions, and also because so many modern Christians remain ignorant of the meditation traditions in their own religious history—the club has been attacked by fundamentalist Christians, and some fundamentalist employees have performed exorcisms in the meditation room. Ed Winchester, the founder of the club, was twice suspended without pay by a suspicious superior who, according to Winchester, was encouraged by the fundamentalists. These days, however, the same pressures that beset the civilian population—the pressures of too little time and too much to do—are more of an obstacle than fundamentalist Christians.

“This is a very transitory, high-pressure place,” Ives continues. “The fact that this group has a twentieth anniversary, small as we are, is phenomenal. We can’t advertise. I put up flyers and I come back an hour later and they’re torn down, as though people have nothing better to do but stand around and wait for them to go up.” The work of fundamentalist Christians again? “Oh yes,” sighs Ives. “Meditation is the work of the devil, you know.” But the real problem, he concludes, “is that people don’t feel like they can spare an hour anymore to go meditate. People literally sneak away from their desks.”

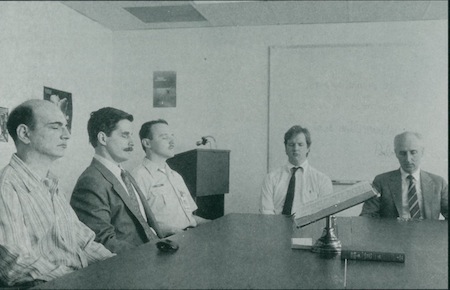

In the Pentagon chaplain’s conference room, I am joined by Ives and three other members of the meditation club at the conference table while three others, one man and two women, sit in chairs near the door so they can slip out without causing a disturbance. In this small, impersonal space full of greenish blue “low bid” carpeting and upholstery, echoing with the doorslams and footfalls of business-as-usual, we close our eyes. Ed Winchester, who still returns for visits since his retirement in 1990, leads us in the “Peace Shield Meditation.”

“I direct my thoughts to the world of my inner being,” he intones. “I forgive myself for all my perceived wrongdoing to myself and to others. I ask for grace to experience my true nature, the God within me, love…” After a period of time in which we are to repeat our “favorite name of God or Creator, Source, the Universe, etc.,” Winchester, a lean-faced man of about sixty, gently urges us to visualize “world leaders, friends and adversaries, joining together in fellowship to resolve issues, forgiving each other.” Through it all waft the sounds of the Pentagon workday, and when we open our eyes the three people closest to the door are gone. Based on the Christian Centering Prayer, the idea of the “Peace Shield Meditation” came to Winchester in a flash of inspiration one day in 1986. It quickly became the crux of an ambitious “spiritual defense initiative” that sought to link people inside the Pentagon and around the world in a unified force field of loving awareness.

Winchester, who was influenced by Transcendental Meditation and was a financial analyst in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, had long sought to prove the value of meditation in the quantifiable terms the Pentagon respected. When a paper he wrote advocating the study of meditation in terms of improved job performance and cost-effectiveness received a cool reception, he persevered through the club, determined to transform consciousness at the Pentagon by teaching one percent of its population to meditate. Eventually Winchester was cosponsored by the Department of Defense and the District of Columbia Department of Corrections to spend a year trying the “one-percent effect” project on the inmates of the Lorton Correctional Facility. Although hard data eluded him, Mayor Marion Barry’s wife, Effie Barry, the warden, and others encouraged Winchester to spend five more years teaching inmates and prison personnel to meditate. In 1986, he launched his Peace Shield Campaign, never losing faith that the effects of meditation could move the world in a noticeable—if not precisely measurable—way.

Over the next few years, Winchester and the meditation club worked hard, organizing lectures and distributing brochures containing Peace Shield instructions and “Personal Peace Treaties.” Although Winchester claims that the highest-ranking military person he saw at a club meeting during this period was colonel, “the fact is at one point I think there were about sixteen generals and admirals who were meditators—closet meditators: they did not allow that to be publicized.”

With the calm, bright-eyed intensity of a man with a mission, Winchester opens a scrapbook of photographs showing a Soviet peace delegation attending a 1988 Pentagon prayer breakfast. Technically, Winchester won authorization to invite the Soviets by doggedly petitioning the Deputy Secretary of Defense, but he believes that the hundred of military and civilian personnel who tried the Peace Shield meditation (though they represented far less than the hoped-for one percent) turned the tide. “The Peace Shield idea was working,” he concluded in a newsletter describing the event. Winchester claims that his meditation practice helped him transform feelings of being an embattled outsider, a “spiritual Rambo,” to feelings of closeness and friendliness even to the supervisor who twice suspended him without pay.

“I had an experience, an inner experience, of the Pentagon becoming my monastery,” says Ed Winchester. “I came to the realization that fighting against the system, at least in my mind, wasn’t working. Somehow I had to recognize that I was part of the system and the system was a part of me. In the end, I got great satisfaction out of knowing that my little peace might be making a contribution to world peace.”

According to Winchester, who was once a brother in a Catholic order, this insight was enhanced by his struggle to bring meditative awareness into even thorny situations at the Pentagon. This kind of understanding is the process of deeper and deeper seeing and self-knowing. It can’t be faked.

“Everyone who meditates in this country is in the Pentagon Meditation Club,” I told my friends after returning from Washington. Planning to lead up to the even bigger Buddhist idea, that the Pentagon too is the enlightened way, I couldn’t help but remember the last time I heard the argument that we’re all part of the war machine. It was the summer of 1977, and I was traveling to Boulder, Colorado, to meet Chogyan Trungpa at Naropa Institute. A friend from college, Rip Westmoreland the son of General William Westmoreland, was driving me there in his rusty, beat-up VW van.

Rip Westmoreland was tall and skinny with a tangled mane of hair. He played the guitar and wrote and drew in a thick black journal with a fountain pen, I thought he was a potential Jim Morrison (who happened to be the son of an admiral). Rip and I stopped to cook dinner one night and he asked me what I knew about Trungpa anyway.

I told him that I didn’t know anything about Trungpa except that he was supposed to be brilliant and wild, somebody to show me how to see myself with fresh eyes, how to connect with reality. I knew there was more to life, to me, than the purely verbal answers I had picked up in college. Turning my back on convention, lighting out for the West, seeking Trungpa, I was taking a brave new stand and reveling in it.

Rip Westmoreland reminded me that there was such a thing as a material world, that it was his van I was riding in, for example. “Your father helped you buy that van, so you bought it with blood money,” I said, with the cruelty of the truly ignorant. “It’s all blood money,” he exploded. “Don’t you know that? Everybody’s money has blood on it.” He made me question what spiritual search had to look like, what outer form it had to take. For a split second, he made me see that there is no “us” and “them,” no “there” to get to before spiritual life begins. It begins where you are.

I never did meet Trungpa. We made it to Boulder and to Naropa Institute. I peeked into a big bare room and a woman appeared and told me Trungpa wasn’t there just then. She asked me what I wanted and my mind went blank. I had never before felt so on the spot, so in question about who I really was and what I really wanted.

I asked Bart Ives if her ever felt like heading west, if meditating ever made him question what he’s doing working at the Pentagon. Sure, Ives concedes. He volunteers that it is conceivable that he could one day connect so profoundly with is ultimate nature that he would stop working at the Pentagon and join a monastery.

But in the meantime, “into the den of lions, as they say. Where are you going to have more impact? The group is more than just a symbol. In the midst of all the pressure I can have an impact individually, by meditating, by showing people that it can be done.”

To the Pentagon Meditation Club, sitting is taking a stand.♦