Between every two pine trees there is a door leading to a new way of life.

John Muir

I would often engage my secondary school students in the childhood art of climbing trees to do a “tree sit” for an afternoon. Inspired in part by John Muir’s penchant for climbing, sitting, and “riding” trees (he knew keenly that such “play” was the seedling of real work), it became one of the most effective lesson plans within my arsenal of activities designed to create experiences for youth. In keeping with the Socratic injunction that my role was to create the “soil” within which the seeds of thinking could take root, and not to teach, I soon marveled at the results of this academic activity. The effects upon the youth in my care as well as those of doing such tree time myself were instructive. It is most likely a difficult stretch of the imagination for many to see the “academic” benefit of such a seemingly frivolous act once beyond childhood, but prior to any judgment one needs to hold the image of fifteen to twenty teenagers ascending into the treescape on any given Friday afternoon following a week-long battery of schooling. After the normal boisterous and exhilarating commotion stirred by their exciting ascent into the canopy, to sense and to witness the silence and calm pervading the deep woods for the following ninety minutes speaks loudly.

What you would have then witnessed on such an afternoon would be a group of youth in Tree Time. A slowing down to a point where one not only can sense and hear their own heartbeat but may even (hopefully) find themselves pondering the resonance between their own and the tree’s heartbeat. It is a time where one also finds oneself doing one’s own thinking. The insight gained from experiences of this nature would be critical, for example, in understanding Julia Butterfly Hill’s two-year act of civil disobedience sitting in the tree called Luna1 to save the 1500-year-old California redwood from the ravenous actions of the lumber industry. Tree Time can bring one to a point where vital questions get asked of us. The taste of this inner state was likewise very helpful when trying to wrap my own understanding around the publishing world’s bidding war over first-time author Jack Cooke’s The Tree Climbers Guide: Adventures in The Urban Jungle in 2016. A rather rare event within book publishing but not so perhaps if the world is unconsciously starved for such adventurous experiences.

Tree Time is something the world could use more of in these times.

Tree Time allows for a heightened perspective. In such “light,” trees are rightly called Elders, and revered teachers. Those steeped in the herbalist tradition have always held such reverence for the tree people. Given a tradition where the language of gesture is understood respectfully, a tree’s ascent into the heights, defying gravity, can be seen as an archetypal impulse to lift the very earth itself up into the celestial vaults of sidereal space and time. Such mindful considering (from the Latin considerare, “to look at closely, observe,” probably literally “to observe the stars”) can be attributed to the “towering cathedrals” witnessed and celebrated by Emerson, Thoreau, and Muir while likewise providing a snippet of understanding into how Jane Goodall’s childhood professed best friend could be a tree. There is something quite important for us to learn here, and worth paying utmost attention to.

Trees communicate something vital. Something, should we have ears to hear and eyes to see, that these times call out for, and display many nuanced expressions toward. Science, via the insightful work of Suzanne Simard2, has brought us the Wood Wide Web and the Mother Tree concepts in forestry that parallel not only the new scientific insights emanating out of the mycorrhizal realm of life, but the deep wisdoms long buried (and too often ignored) within the traditions of women and Indigenous people worldwide. I am reminded of Thomas Berry’s view into the future where the building blocks of the world’s “Four Wisdoms,” much like the four archetypal elements3 themselves, are the requisite needs (wisdom) for navigating the future’s perilous path. I pair his wisdom of science to the wisdom of women, and the wisdom of Indigenous people to the wisdom of mythic tradition and have sensed deeply the gift of Tree Time when holding these pathways in relational perspective. Experience that elevates my own thinking and feeling toward a more heart-felt interdependent relationship with nature as well as a more inclusive, reciprocal exchange governing all outward action.

Stately trees do remind us of the resiliency of nature; being sessile creatures, they have learned to transcend time, to grow, and heal. They learned long ago that the key to life resides in cultivating good relations, standing deep within a kind of knowing that surpasses human knowledge. We often equate their attributes and virtues to ourselves through statements like “sturdy as an oak” and “as flexible as a willow” yet the balance between inner feeling and outward expression goes unrecognized. Richard Higgins4 reminds us that for Thoreau “trees were wordless poems…and the message he heard from them was one of life itself,” for trees were also guides and companions to Thoreau’s soul. Thoreau saw trees as upright and virtuous and the nobility of the vegetable kingdom because they point beyond themselves. They were his “mythic tablets,” reminding us, like Julia Butterfly, that humans “cannot converse with the spirit of the tree he fells,” and that we “cannot read the poetry and mythology which retire as he advances.”

Trees also exemplify renewal and persistence, and even take on moral agency. The character called Treebeard in J.R.R Tolkien’s Lord of The Rings is one such example of taking on personhood and no longer being relegated to a mere peripheral position. But recent real-time examples mirror the same, such as the Whanganui River being recognized as a legal person by the New Zealand government (long understood by Indigenous Maori people), or Mark Zuckerberg’s attempted purchase of Hawaiian Indigenous lands. The land and all its physical and metaphysical elements are viewed as an indivisible, living whole, and thus possess all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of a legal person and are granted the same moral agency. For native Hawaiians, the land is an ancestor, grandparent, and elder. To them, they remind us of what we have forgotten—that you just don’t sell your ancestors, for that is what separates us from the land.

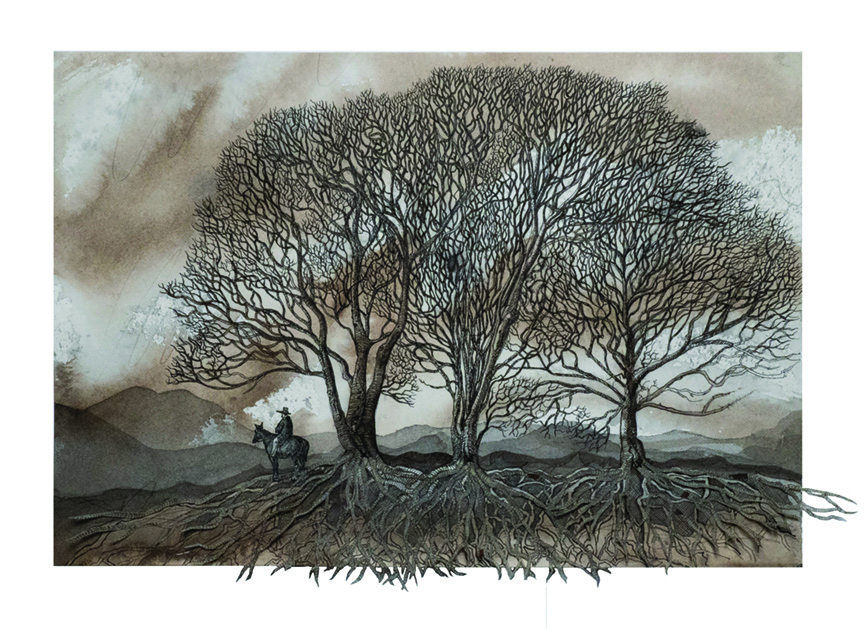

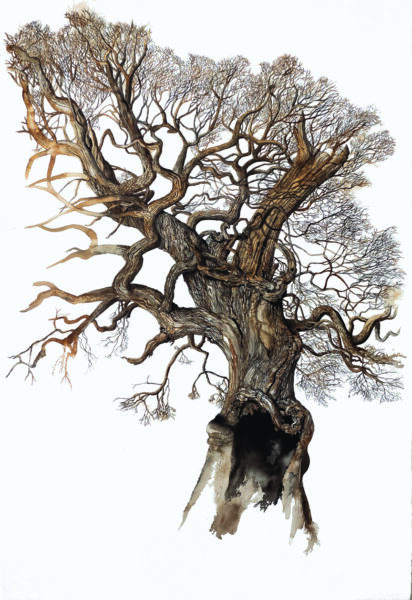

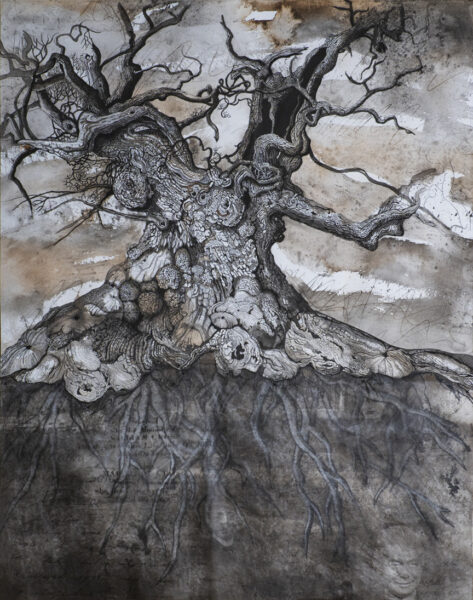

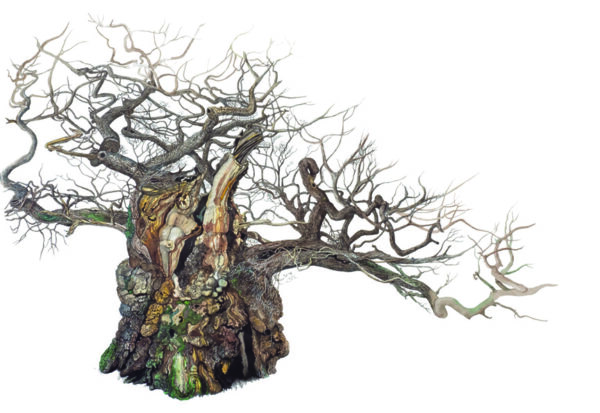

What has always bridged that separational gap within our human mindset, feeding and nourishing both heart and soul, has been the arts. Mythic stories and imagery, or what Tolkien calls our “secondary world,” help in re-introducing us to our primary world in a process he calls “recovery.”5 Such a recovery of a sustainable myth was paramount to Joseph Campbell and was seen as the task of the artists of one’s times to “wake” us from the “sleep” of familiarity. In keeping with such faith, my adherence to and practice of Tree Time enabled me to recognize the real essence art of my long-time tracker friend Mark Elbroch’s mother. In keeping to the truth that the “fruit doesn’t fall far from the tree,” Victoria Elbroch6, along with technical support from her husband, Lawrence, has gifted these times with a study of trees that is both mythic in nature, and a living vibrant example of the process of recovery Tolkien so eloquently speaks to. As our trees and forests are likewise “on the move,” as in Treebeard and the Ents of Tolkien classic myth, such iconic imagery (so beautifully gracing this article) serves well in recovering that vital link mirrored inwardly when one learns to stop, slow down, and do a bit of Tree Time.

One need not necessarily sit high in a tree to allow the wisdom of a tree to train our sight to something higher than mere “board feet,” a truth served well by such representatives. History has borne out the recognition that few stand tall, like the pines, rooted as we sit in the sterilized soil of our own making. Higgins reminds us that trees were Thoreau’s “shrines” and “burning bushes,” or a “sanctum sanctorum,” for forests were accorded a sacred place in the great mythologies. “What does it matter” Thoreau wrote, “if the outer [eye] is open, if the inner door is shut?” Beauty must be in our minds when we go forth for “we cannot see anything until we are possessed with the idea of it, take it into our heads.”

Thoreau truly had faith in a seed. The loss of biodiversity, as in the current departure of trees via longhorned beetles, ash borers, and adelgid aphid-like insects, or the numerous pathogens increasingly on the rise that inadvertently endorse systemic imbalance, requires the seed of a new idea. Imagery has long directed our attention within various fields of thought. The evolutionary tree of science, the Tree of Life from Christian or Norse mythology, or the images we carry from childhood stories found in numerous fables and folk tales—all these images carry the seed of a higher, elevated thought. Much of our ancestral knowledge is synonymous with the knowledge of trees, and they have been good companions to us along the journey.

We are not only in dire need of a deeper experience of trees today, but we are also in need of the endurable gift of hope they provide. Jane Goodall tells us that hope is that virtue by which we take responsibility for the future. Hope, like the trees themselves, asks something of us. Let me leave with what artist Mary Oliver so eloquently invites us to do: “Pay attention, be astonished, and tell about it.” ◆

All art by Victoria Elbroch.

1 The Legacy of Luna: The Story of a Tree, a Woman and the Struggle to Save the Redwoods by Julia Butterfly Hill.

2 Finding The Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest by Suzanne Simard.

3 Earth, Water, Air, and Fire.

4 Thoreau and The Language of Trees by Richard Higgins.

5 Tolkien: On Fairy Stories edited by Verlyn Flieger.

6 Ancient Trees by Victoria Elbroch.

This essay appears in Parabola’s Summer 2022 issue, “Ancestors”, which is available to purchase on our online store.