Transforming repetition into renewal

The conjunction “new” and “year” is in itself a kind of inner contradiction, for a year is something that repeats itself again and again while “new” represents change, the way out of the endless cycle. The fundamental structure of any year is therefore a continuous repetition of the year that has passed. Once more we have autumn, winter, spring, and summer, once more the short days and the long, the rains and the dryness, the cold and the heat. For sure there are small variations between one year and another but the expectation is always for something truly new. For something different.

The same constant repetition of the years is not confined to the weather or the seasons. This repetition and routine are the pattern of life as a whole. With a few rare exceptions man’s life flows along with the same cyclic regularity. Even those events that hold, supposedly, some kind of drastic change—birth, marriage, death—quickly fall into a set pattern. For most people these things are so similar that it sometimes seems as though they are experienced not by real people but rather by some archetypal figure, a stereotype, which has acquired the power of life-like movement and which in a dozen different guises goes from ceremony to ceremony, repeating again and again the same movements and postures, the same words, even the same feelings. And human beings themselves, living people with their own personalities and lives—what about them? It seems that they are as those who sleep, living their vegetative lives as if they were potatoes. Yes, they await a “new” year, something that will come from without to change things.

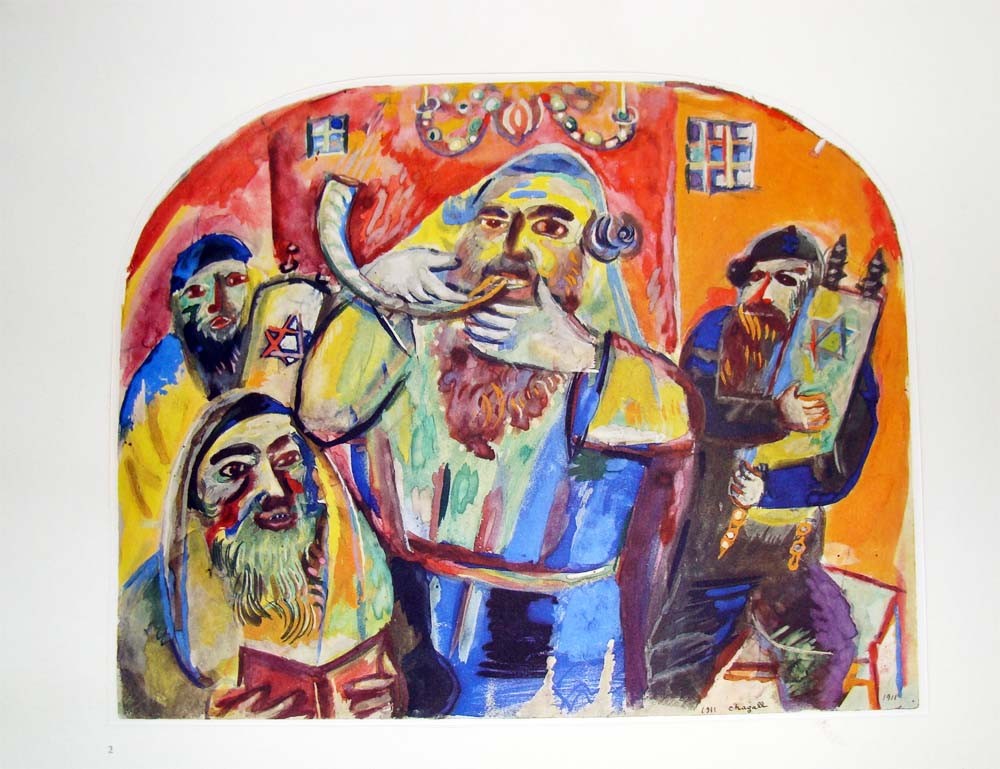

The Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, is the beginning of the first day of the new year and its central feature is the blowing of the ram’s horn. This horn is not, nor has it ever been, a musical instrument. It emits only a harsh blast, a wailing, groaning, threatening, annoying, and frightening cry. The blowing of the ram’s horn at the start of the new year is a hint to sleepers to awake from their slumber, it is a call to examine their souls and improve their ways. The ram’s horn therefore is not intended to beguile the ear, but to arouse, shock, provoke those who sleep. Its wailing is a call to awaken from the lethargy of routine, to repent. The essence of repentance is actually the ability to renew, the awakening of the capacity to be oneself instead of a copy of advertisements, or neighbors, even of oneself when younger and more authentic. This raises the question of whether repentance is really the way to restore the original, authentic experience of independence, since it often means a return to that same religious pattern that for many is not a personal step but a return to family, to nation, to the continuation of the path that has been neglected for a generation or two. And is not religion, with its thousands of fixed rules, its precepts and deeds, its commands to “do” and “not to do,” itself a part of this same unending repetition, this same routine multiplied a hundredfold?

The religious individual is in unceasing conflict with the “ordinary” and at every step of the way clashes with it, in eating, in drinking, and in working/worship. It is this clash that stimulates change, the break in the continuum of routine. Each and every act calls for a minute pause, a tiny breathing space from the rat-race; we pause for a blessing, prayer, or ritual hand-washing, and for a moment pass to another level of being that does not stem from and is not bound to the daily round of life. One is still, in principle, obligated to direct one’s heart to what one is doing. For one may be able to deceive one’s fellow regarding the sincerity of one’s intentions, bit one cannot deceive the Almighty or console oneself with the thought “No one knows.” In every other aspect of life, a man can continue for years to be almost a zombie, without ever being required to do more and without feeling any obligation to himself to give of himself anything more profound. Such a man may be an excellent worker, an outstanding educator, a spiritual leader, a faithful husband, or a loving father—and all these qualities may be nothing more than a mask, and worse, a mask with nothing at all behind it.

A story drawn from the heart of Jewish folklore relates that when King Solomon in his wisdom wrote in the Book of Proverbs: “The fool believes everything he is told” (Proverbs 14:15), all the fools in the world were stunned and they convened a huge international congress to deal with the question. What would happen now that Solomon had discovered the gullibility of the simple? Previously, the wise were indistinguishable from the foolish and thus the latter could hide from the world, but what now? After lengthy discussion, the fools arrived at a solution that would enable their continued concealment: from now on they would not believe anything. And so it is to this very day. For this reason, when people speak of their inability to believe, of the absurdity of faith and other simple or complex problems of this nature, one feels the urge to ask: Were you at that Congress?

This is not to say that the path to faith is easy. It is not. Neither for someone who has grown up in a “religious” home, nor for one who has grown up in a secular atmosphere. And this is not surprising; the way to faith is never a smooth one. It is not for anyone a broad and even highway along which people progress at the same pace, but always a tortuous, winding path—very personal and private. A certain tzaddik put it with profound simplicity: Because I know that God is great, because I know that I alone know and no one else can know as I do. Someone else may know more than I do, know more deeply, more comprehensively, more perfectly, but in the end, the experience of God is personal and unique and can never be transferred to another.

When one tastes fruit one can describe the experience of what one ate, and how one ate in great detail, but the essence of the eating, the taste itself, cannot be described or defined—that is something one has to find our for oneself. So it is written, “taste and see that God is good.”

Who is capable of reaching this stage, of “tasting from the tree of life?” Should one not first attain greatness, experience, be outstandingly wise, pure in thought and feeling in order to be “religious?” This question has no clear answer, any more than does the Torah reading for Shabbat before Rosh Hashanah: “It is not in heaven that thou should say: ‘Who shall go up for us to heaven and bring it unto us that we may hear it and do it?’ But the word is very nigh unto thee in thy mouth and in thy heart that thou may do it” (Deuteronomy 31:12-14).

Where is the same faith to be found? Not in heaven and not beyond the sea. It is incomparably close—on your lips and in your heart. Because—and this is true of the most penetrating insights of theology as it is of personal experience—every man speaks an abundance of faith and certainty. It often happens that he does not give account to his heart of what his mouth says, and he cannot discern what his heart truly believes, yet, every time we use the cliché—which is actually an expression of profound faith—“Never mind; it will be alright,” or in the words used to comfort a crying child, we have a real and true expression of belief, or faith, an acknowledgement that life’s obstacles can be overcome with honor and wholeness. In all of these, it is faith that speaks.

The man who denies all belief and yet who believes with all his heart in the eternity of Israel, the man who takes nothing for granted, whether in religion, tradition, or history and who nonetheless holds to those things that he believes to be good and honest, whether he is educated or simple, whether perplexed or clear-sighted, has an abundance of real faith, a faith that is found “on their lips and in their hearts.” It is inhibition that induces a man to think that he has no part in believing, because he is convinced that true religious faith is somewhere far away, in the heights of heaven, beyond the spheres. He does not seek in the places nearest to him, because he does not nurture or develop the seed within himself. It is interesting to note that the word “belief” in Hebrew, emunah, has the same root as the word “to foster,” to care for the suckling. The seed of faith must be tended, nurtured as a living organism is nurtured; it needs room to grow, a space in which it may find its true expression. It should not be left to its own devices, or await the authorization of the Congress of Fools—this belief is found so close to each one of us that it requires only “to do it,” to bring it to realization.

Thus year follows year in endless succession. “What was will be again.” The individual may enjoy this endless repetition throughout his life without ever reaching any kind of reckoning. Every year will be for him just one more old year, the same old dream without end, the same vicious circle from which there is no escape. That is why the schofar is sounded, its simple ear-assaulting cry. Its wordless wailing (since no words are understood by all) consists of two broken blasts, a lamenting for what was, for what has been. This is followed by two warning notes, for what may still lie ahead to entrap and degrade, and culminates in two shouts of victory: the promise that, in spite of everything, there is a possibility that the coming year will be more than a mere repetition of its predecessor, that within the cycle of the seasons there is room for hope that the coming year may be truly “new.” ♦

From Parabola Volume 33, No. 3, “Man & Machine,” Fall 2008. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.