Head down, hugging a grocery bag, I hurried past gutted buildings and empty lots, back to my ex-boyfriend’s apartment in Hell’s Kitchen. It seemed like a good idea at some point, having dinner together as friends. But the little Spanish market on the corner of Ninth Avenue and West 35th Street was the only pocket of light and warmth for blocks. Ahead there was nothing but deserted streets and a cold wind blasting in from the dark Hudson River.

I wondered what I was doing in this godforsaken place, when exactly I had become so insubstantial, agreeing to go out to the store alone at ten, agreeing to do all kinds of things I didn’t really want to do. I shivered a little with self-pity.

Manhattan in the 1980s was a gritty place. I used to think of it as having a dark glamour but no more. A few years before, I had come to Manhattan like someone drawing close to a fire. I wanted to be warmed, enlightened. But nothing turned out the way I hoped, not love, not work, not life. I pictured myself a waif huddling along in a bleak neighborhood, bringing her own pasta to dinner. The image was so pathetic that I savored it, a fragment of a modern Dickens tale.

I was passing an empty parking lot on West 35th Street near Tenth Avenue when three men rushed out at me from the shadows of a gutted tenement across the street. I heard them before I saw them, pounding toward me, whipping past me, stopping and wheeling around, taking up stations around me, as purposeful and practiced as football players,

or predators.

For a few moments, we stood and stared at each other. Incredibly, I was gripped by an impulse to smile and make eye contact, to diffuse the situation by establishing that we were all fellow human beings, even potentially friends. They were not interested in making friends.

They were pumped up, panting, panicking. Two looked like lanky teenagers, wraith-like in dark hooded sweatshirts, eyes glazed with fear. The third was older and much bigger. A faded green sweatshirt stretched taut across his chest. His wrists dangled out of the sleeves, as if he was wearing someone else’s clothes, and maybe he was because the next day there were reports in the papers of escaped convicts in the area. His broad face was grim.

Darting behind me, he jerked his arm tight across my throat. I felt his chest heave and heard the rasping of his breath. Staring up at the side of his face, I saw a long shiny scar. It was strange to be pulled so close to someone intent on harming me, but even stranger was the sudden pang of compassion I felt for him, for the wounding that had made the scar, for the suffering he must feel to be doing this.

It was the strangest thing. Brain studies show that the readiness of the body to move precedes our awareness of being willing and intending to move, that everything that happens is dependent on thousands—millions—of conditions and turnings of little wheels that take place below our ordinary limited level of consciousness. But the burst of compassion I felt didn’t feel like an unconsciously conditioned response, like the impulse to smile at my muggers—like almost everything I found myself doing. It was as if another, higher consciousness was descending into my consciousness.

I read a story about how no animals were found among the dead after a tsunami; sensing the infinitesimal vibration of what was coming, they headed for higher ground. Even before I could grasp what was happening, it was as if the animal of my body and my physical brain was heading for higher ground, opening to receive help from above. Even before I glimpsed the light, my heart was opening to a kind of feeling that cannot be created or destroyed by anyone, only received.

“Money!” His voice was a rasp. His massive arm was pressing down on nerves that made it impossible for me to move my arm to reach the money in my front pocket, and I couldn’t talk to tell him this. “Money now!” He pulled his grip tighter. My vision started going black around the edges. I remember thinking the situation was absurd. I couldn’t talk. I couldn’t tell him that I needed to be released to reach my money.

But I also glimpsed the larger absurdity of the larger situation: I was a young woman alone at night on a deserted side street in Hell’s Kitchen, drifting along thinking about what she liked and didn’t like about her life, what she judged to be good and bad, dreaming that she was in control of what happened, all the while oblivious to reality. “When a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully,” wrote Samuel Johnson. Mind suddenly terribly concentrated, I saw I was in real trouble.

My brain started working faster than it had ever worked, calculating the size and strength of my attacker, the agility of two young men guarding me, my own capacities and the probability of this or that happening if I did this or that. My brain calculated and recalculated every aspect of the situation I was in until it concluded there could be no escape, no movie-like scene of flipping my attacker with deadly martial arts skills, throwing him into his assistants and running away. The reality I confronted was inconceivable, unworkable. My brain crashed, the screen went white. I surrendered.

It was then that I saw the light, just a glow at first but growing brighter until it became dazzling, welling up in the darkness to fill my whole body and mind. As it grew, this light gained a force and direction—an authority unknown to me. I remember marveling at the building intensity and intention, wondering where it had come from, not just low down in my body but from unseen depths—and then it became a column of brilliant white light that shot out of the top of my head, arcing high into the night sky.

A Tibetan Buddhist I met who read an earlier account of what happened to me that night told me it reminded her of a Vajrayana Buddhist practice called phowa. I also learned that Vajrayana means “diamond” or “thunderbolt” vehicle, which I understood personally because everything about the experience dazzled, was charged with force. Phowa is described as a practice of conscious dying, or transference of consciousness at the time of death, or even a flash of enlightenment without meditation. Tibetan lamas imprisoned by the Chinese were said to be able to leave their bodies this way.

But this—happening to someone who could barely sit still for a twenty minute meditation—didn’t amaze me as much as what unfolded next. The column of light joined a much greater light that descended to meet it. Behind the abandoned tenements, behind my attackers, behind all the appearances in this world, there was a gorgeous luminosity. It was clear to me that this light was the force that holds up the world, into which all separation dissolves.

I realized that I could see myself and my attacker from behind and above. I watched myself gasping, watched my knees buckling, watched myself sink, watched myself looking up at the light. And then I was embraced by the light.

Science argues that while near-death experiences feel real they are simply fantasies or hallucinations caused by a brain under severe stress, and certainly my brain was under stress that night. A choke hold can kill in twenty to thirty seconds. Someone skilled in martial arts can knock someone out within eight seconds using such a hold, and brain damage can happen after about fifteen seconds because stopping blood flow to and from the brain can lead to brain hemorrhage, and the pressure on the heart can cause it to stop.

But science can’t account for the intimacy—for the extraordinary presence—of the experience. I didn’t just see the light, I was seen by it, and not in part but in whole. I knelt on the sidewalk, looking up at a light that was not separate from wisdom and love, a light that descended to meet me.

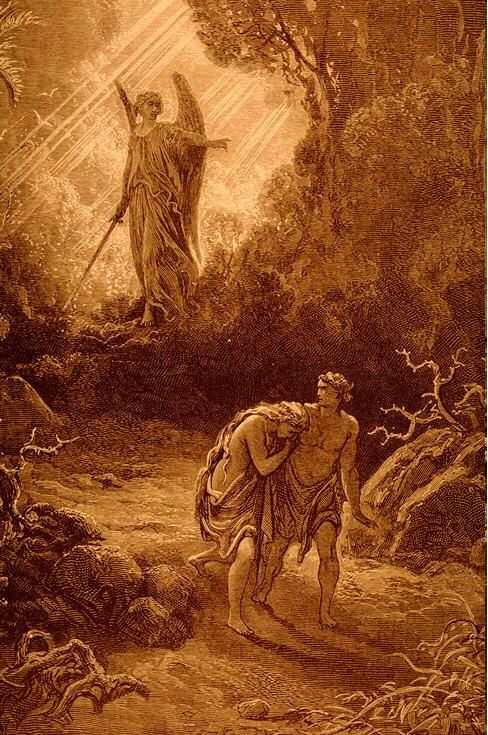

Afterwards, I heard the phrases “communion of saints” and “heavenly host” and “vault of heaven” and felt a thrill of recognition—my mind grasped at religious metaphors to describe what I had seen. The light was vast, vaulted, and all around. I sensed the presence of beings, ranks of beings, an ascending multitude, turning, moving, altogether forming a great witnessing consciousness, in every detail and part infinitely finer and higher than my own. There are no words for the majesty and radiance of what I glimpsed and how it made me feel, lifted, seen, accepted into a vast whole.

A particular being drew very close, looking down at me from above with love that had a gravity and grace unlike anything I known. It proceeded to search me, brushing aside everything I thought I knew about myself—my name, my education, all my labels—as if it was not just unimportant but unreal. I once came up with an awkward personal metaphor for the urgency of this part of my experience: fire fighters searching a burning building, shining a light through smoke, looking for signs of life while there was still time. Strangely, I sensed that the urgency and concern weren’t for my physical life.

Finally, the searching stopped. The light came to rest at a particular spot in the center of my chest. It poured through me. I was very still, in thrall, humbled, aware that what was dear and good to this light was not any quality that I knew, but something deep and mute in my being. How long was I held in the grave and loving gaze of this higher being, this angel of awareness? Moments probably, but time meant nothing. I had the sensation that my whole life, lived and as yet unlived, was spread out for examination, that my life was being read like a book, weighed like a stone in the palm of a hand.

I saw that everything counted—or, everything real, every tear, all our suffering. That I didn’t “believe” in

any of this—that I was too cool, too skeptical, too educated to be dazzled by experiences that were clearly, had to be, subjective, that I would never resort to hackneyed religious metaphors, and images like weighing and reading—that also didn’t count. My opinions about what I believed or didn’t believe, what I was capable of or not capable of, were just smoke to be brushed away.

I was lifted up into a field of light and love, flooded with a feeling of liberation, of rejoicing. It was like flying, rising above the clouds into bright sunlight, except that it was more radiant. It was exalted, sublime yet welcoming. Everything I knew fell away, yet I felt completely accepted and acceptable, completely known, completely loved, completely free. There were no words, just experience. Yet ever since, I have wondered if this is what salvation is like, to be lifted up out of the fog of separation, of sin, of forever missing the mark, and delivered into the whole, into the reality behind the appearances of the world.

It was clear that this radiant light, this loving consciousness, held everything that is. It was the alpha and omega, the particle and wave, the unifying force of the universe, suffusing us, carrying us when we leave this body, accompanying us always and everywhere, appearing in us when we are open to receive.

I knew I wouldn’t stay long in this radiance, in this sublime love and freedom. I was still sinking to my knees on a dirty sidewalk in Hell’s Kitchen, still struggling to breathe. Yet, as strange as it sounds, I wasn’t struggling inside. I was still. It felt as if I was falling to my knees in prayer—surrendering, not to this attack but to something that was infinitely higher. I understood that a life could have a different sense and meaning, that it could be spent seeking, purifying, practicing—I couldn’t find a word that conveyed the glimpse I had better than the words of the prayer, “Thy Kingdom come, Thy Will be done, on Earth as it is in Heaven.”

The being who searched me—who saw me inside and outside, past, present, and future, told me without words to relax, the struggle would soon pass, I would not be harmed. I would return.

I would go on. The light withdrew.

My attacker loosened his grip just enough to allow me to reach a ten dollar bill in the front pocket of my jeans. I threw the bill on the ground. My attacker jerked his arm off my throat, scooped up the bill, and ran off with the others. I stood up. I had my life back. I stared up at the night sky, then down at the ripped grocery bag, wondering why the muggers hadn’t taken the cigarettes and the six-pack of beer.

“Of all the pitfalls in our paths and the tremendous delays and wanderings off the track I want to say that they are not what they seem to be,” writes the artist Agnes Martin. “I want to say that all that seems like fantastic mistakes are not mistakes, all that seems like error is not error; and it all has to be done. That which seems like a false step is the next step.”

I walked back to my ex-boy friend’s apartment, shaking with sobs. I wasn’t harmed. Settled at the long dining room table in his book-lined loft, tears streaming down, I choked out the story, insisting that I wasn’t harmed. Never mind the weeping, I told him. I was fine, really, perfectly calm at center of the storm, you see. My ex-boyfriend looked miserable. The crying went on and on. He pushed a twenty dollar bill across the table towards me, repaying me for the groceries. I brushed it away and he pushed it back. Just take it.

We aren’t in control in the way we think we are, I told him. Things happen, even terrible things, but they are not what they seem to be. And we aren’t alone. There is a light, a luminosity behind the appearances of this world. There is a luminous, loving intelligence above us, watching over us, caring for us. I knew how this sounded. Religious, mystical, unbelievable. Do you believe me, not about the mugging but about the light? He shook his head no, scowling softly, sorry for me. He just could not.

In the weeks and years that followed, I learned this is how it goes with personal revelation. I was an unreliable narrator, no more so than any other ordinary human, but still very limited, subject to dreams, to the wheels and levers of conditioning. But the experience never grew dim. I told it to people I trusted, or the dying. I told it to my father in his last days, and to another dear old friend near his end. I sure hope you’re right, he said.

What we really have to share is not any spiritual treasure we imagine we have stored up, but our poverty, our common human situation, our inability to know.

Many years after that night in Hell’s Kitchen, I still drift through the world lost in thought, captivated by stories and images. But I know a greater reality and a greater awareness exists. I know there is a truth that cannot be thought, only received.♦

Tracy Cochran, “The Night I Died,” a brush with death leads to a glimpse of Light, PARABOLA Volume 38, No. 2, Summer 2013: “Heaven and Hell.” Our 150th issue is available here. Like what you’ve read, why not subscribe?