We sat, unmoving, in the darkness of the movie theater as the first notes of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s overture played—a foreboding orchestra followed by sinister electric guitar. It was the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, and we had been forbidden to see it. I was barely seven years old.

With guilt-ridden anticipation, my older sister, Betsy, and I took in the opening scene—a bus chugging hurriedly along a winding road, kicking up dust in its path. When it reaches its destination, hippies file out, looking hot, exhausted, but jubilant after a long trip to whatever brought them to the middle of the desert. It could have been the scene of a ‘70s peace rally, if not for the Roman soldiers, guns, and a giant crucifix strapped to the roof of the bus.

In scene after scene, our wide innocent eyes took in the sweaty, wild dancing and raucous music. I had never seen women behave like this before. They were leaping, flipping, shaking their hips in bell bottoms and bikini tops, belting songs in raspy altos. The guys had long wild hair, sandaled feet, and tossed out lines like “Hey, cool it, man.”

That guitar, those voices, the energy—it all set off sparks in my brain and snaked down my spine. Something had found me, plugged itself in, and took root in my being. Hello, my body and mind seemed to say in unison. We’ve been waiting for you. Where have you been?

Outside of FM radio, this was my very first exposure to rock, as I was still a year or two from discovering my middle brother’s record collection. Held in the spell of that dark theater, I experienced the heady mix of something both prohibited and enjoyable. As Barbra Streisand sang in Funny Girl, “it’s a feeling I like feeling very much.” Except this wasn’t my father’s musical. And it certainly wasn’t my mother’s.

Jesus Christ Superstar was the most exciting, electric, glamorous thing I’d ever seen. It awakened the future rock chick in me, a title I’ve occasionally found offensive but now would wear with pride. Of course, our parents never knew Betsy and I had exposed our souls to a forbidden movie. It’s safe to say that turned me on as much as the movie itself.

In our house, The New World determined which movies we could see and, more importantly, which ones we couldn’t. Not the Motion Picture Association of America, not Siskel and Ebert’s Sneak Previews, but The New World, a weekly newspaper published by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago. The paper’s Moral Classification of Movie ratings were as follows:

- • A1 (morally unobjectionable for general patronage)

- • A2 (morally unobjectionable for adults and adolescents)

- • A3 (morally unobjectionable for adults)

- • A4 (morally unobjectionable for adults, with reservations)

- • B (morally objectionable in part for all), and

- • C (Condemned).

As kids, or, more aptly, as people living underneath my mother and father’s roof, we were allowed to see A1 movies only. A2s were considered only after I entered my teenage years and extensive further analysis—unless the movie featured Tom Hanks, which earned an automatic stamp of approval.

This limited us to a maddening list of maybe a dozen or so movies a year. In 1973, the year Jesus Christ Superstar came out, Fiddler on the Roof, Lassie Come Home, and The Ten Commandments made the cut. Betsy really wanted to see Jesus Christ Superstar. Five years my senior, my sister willingly went to the local stage productions such as Music Man and Hello Dolly that Mom took us to. I loved all kinds of music but found most musical theater a bit lame.

Every week, we waited for The New World to arrive in our mailbox, our cinematic fates held in its pages. When Superstar finally made it to the Moral Classification of Movies page, Betsy was crushed to find its A3 rating—an equivalent of a C from Mom and Dad. This meant we’d have to organize a stealth outing—an uncharacteristic move for my sister, a theme that would become increasingly common for me.

That’s how we found ourselves, on a bright, hot, summer afternoon, in a movie theater the next town over, where our older sister Kris worked as an usher, to see the forbidden Superstar. Not one to be hemmed in by our household rules, Kris was a willing accomplice for our mission and snuck us in with a sly grin. I felt my nerves explode as I pushed my way through the turnstile at eye level, as though entering a portal to a place where fallen children viewed A3 movies and above (or was it below?).

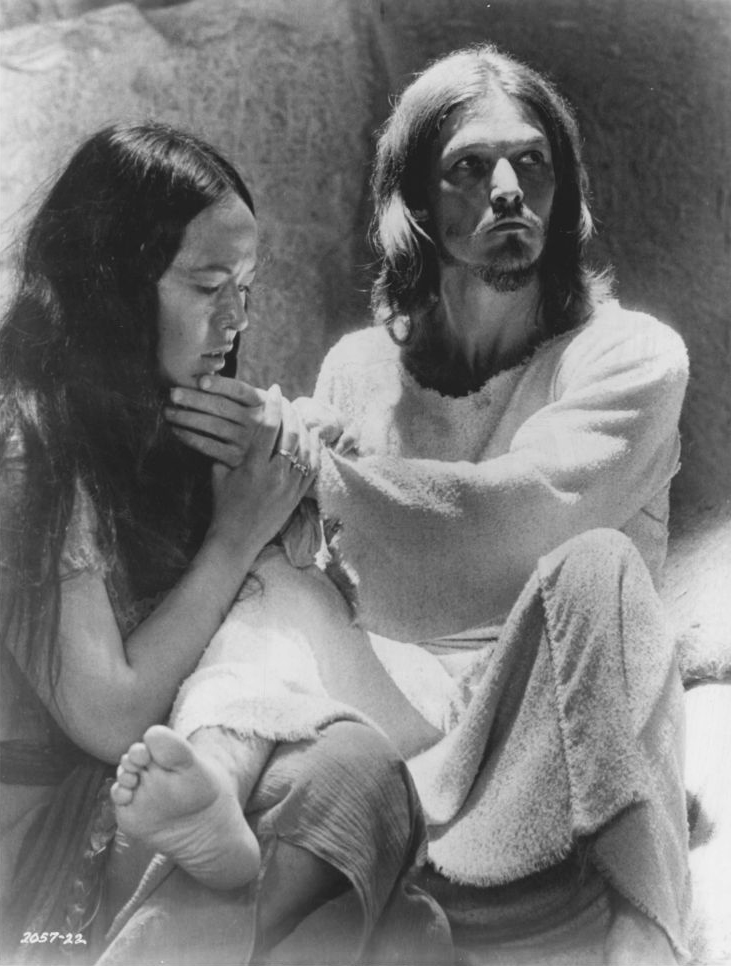

It doesn’t surprise me now, on the film’s 50th anniversary, that Superstar earned its rating of A3 from the Archdiocese—the scene of prostitutes hawking their wares in the temple, however fleeting, alone would summon scorn. Plus, it was a very experimental film for its time, humanizing Jesus Christ as a man who flipped tables in anger, expressed anguish about his chosen fate, and yielded to Mary Magdalene’s touch.

What does surprise, maybe even shock me, is the Motion Picture Association’s G rating, a detail I never noticed until I sat down to write about one of the most formative movies of my life. All these years, in my memory, Kris snuck us in due to the film’s R rating. Today, when I consider the violent forty-lashes scene, or Judas’ explicit suicide as he self-destructs with remorse—not to mention the Crucifixion, when actor Ted Neeley was painfully stretched on a wooden cross in 100-degree-plus heat in nothing but a loin cloth while director Norman Jewison got a perfect take—the G rating stuns me. My sister and I had covered our eyes during that disturbing scene, catching a few daring glimpses through our fingers. Jewison wanted viewers to be horrified. Mission accomplished.

After realizing that I had misremembered the movie as an R-rated film, I felt the need to track down an old copy of The New World, to make sure I remembered the Moral Classification of Movies rating system correctly. Or had I gotten that wrong, too?

I told an old friend, who was also raised as a Catholic in Chicagoland, about my quest to find a copy of the old ratings. She not only remembered The New World, she knew that it was still being published and was now called The Chicago Catholic. “Why don’t you visit the paper’s archives?” she suggested, knowing how I loved to disappear down research rabbit holes. I hadn’t considered that the paper might still be in business, when newspapers around the country were being decimated every day. I easily found the phone number for The Chicago Catholic’s archives and records center and scheduled a visit for the following week.

On the day of my appointment, I found myself trembling with anticipation at seeing old copies of The New World. For the hundredth time since I started to write about my childhood, I questioned the sanity of digging up old ground. What was I doing on Archdiocesan property, willingly confronting a past self I resembled less and less? The writer and historian in me trudged on, so I loaded up the microfiche machine, careful not to let the film spin off its delicate reel. Memories of library visits from childhood kicked up dust in my memory.

There’s no way to search for an exact date or term on microfiche. You just scroll, slowly turning the knob, and scroll, and scroll some more, until your tired eyes finally land on the yellowed article you came searching for. As I scanned through week after week of movie ratings, searching for the issue with Superstar, a couple of things became abundantly clear. While there were only two or three A1 movies week to week, there were as many as a few dozen B and C movies in every issue. Dirty Harry, Clockwork Orange, and Carrie—the latter with scandalous themes of witchcraft, mass murder, and menstruation—were just some that got slapped with a C.

Another detail caught my fatigued eyes as I skimmed The New World. One of the C movies listed was Deep Throat. It took me a beat, but wasn’t that…. porn? I skimmed through more of the C ratings. Schoolgirls Growing Up. Daughters of Satan. Suburban Wives. A quick Google search on my phone revealed these were X-rated affairs once labeled as sexploitation, typically shown at the drive-in theater a few towns over from where I grew up.

I was dumbfounded. Why would X-rated movies even be of consideration to the conservative New World readership, I wondered? And what was the New World’s process—did the staff merely skim the week’s local movie listings and automatically label any and all X-rated films as Condemned? Or did the The New World’s movie critics, clergy men who took oaths of celibacy, actually spend several hours a week watching porn?

I was disturbed and fascinated by these questions. The only issue that had plagued us as kids was: What movies did The New World deem unobjectionable for all? There, in the Archdiocese archives and records center, on a blurry microfiche screen, my upbringing was brought back into sharp focus: The list of things thou shalt not do was infinitely long, but the list of approved activities, not so much. This, in a nutshell, was the way we were raised.

“How is it going?” The archives librarian asked me.

The sound of a voice snapped me out of the fog I had disappeared into. “Huh? Oh! Yeah, it’s going….” I nodded, struggling for composure. “It’s going really well.”

“Good. Let us know if you need anything.”

If only you knew, I thought, about the time traveling I was doing in my head. I had ventured on what I thought was a fact-checking excursion and instead found a trap door to a part of my childhood that I hadn’t visited in decades.

I sat, pretending to read the screen in front of me, immersed in the thoughts that found themselves swirling in my mind. The Church had dictated what we could say or do. My parents never questioned the Church, and we were never to question our parents.

With no forum for discussion in our family, let alone debate, I was left to wonder and wander on my own. I snuck behind my parent’s backs to see banned movies. I discovered rock music—my first real love—on my own. I listened to rock albums when they weren’t home, or in the basements of friends’ houses. I lied about going out with a girlfriend from the pool so I could see The Cars at the Rosemont Horizon, my first real concert.

I drove around Chicagoland and auditioned to sing in bands right after high school without a chaperone—looking back, a parent really should have been with me. I left home for my first real singing gig, a touring club band earning $300 a week, with a disapproving “if that’s what you want to do with your life.”

Anything involving long hair or short skirts or loud guitars was scowled upon. Both my parents were part of the Silent Generation, born during the Great Depression. We were two generations removed from each other, both in age and culture. They had once danced to Stan Kenton; I was fed a diet of my older sibling’s ‘70s album-oriented rock before moving on to the hair metal, new wave, and grunge that informed my Gen X soundtrack.

As I sat in front of that microfiche, staring down my past, I thought about my previous selves—as a child, a preadolescent, a teenager, a young adult—and saw a highly curious soul who indulged her obsession with rock ‘n’ roll despite her parent’s firm disapproval. I scanned my past behavior for justification for their disdain and came up empty. I got almost all As and Bs in school. I placed at the top of regional piano competitions. I finished high school, trade school, college. It wasn’t like I was hanging out backstage, seeking to be a groupie. Rock channeled my rebellious energy. It probably saved me from channeling that energy in destructive ways. In fact, I know it did.

But when I looked again at the movies offered in 1973, I realized I couldn’t lay the blame for my childhood’s narrow cinematic choices solely at my parent’s feet, or even The New World’s. Family-friendly films were in scant supply. Pixar hadn’t been created yet. Even Disney films and so-called family movies like Old Yeller involved death or violence. The movie industry churned out horror flicks, sexploitation, and, as much as I hated to admit it, other films only appropriate for adults. Our parents hadn’t invented the wide chasm between the films we were allowed to see and the majority of films available—this, I blamed on the industry.

I finally turned off the microfiche machine, got up, and gathered my things, thanking the librarian on my way out. The past had revealed itself in ways I hadn’t expected. While shaking loose old memories, I was also finding new appreciation for my past self. I had to nurture my passions on my own; no one held my hand, but I did it anyway.

Although I remind myself time and again of the era in which Mom and Dad had parented, and I never question how much they had loved and cared for me, I felt a huge pang of sorrow that they never acknowledged the bravery and courage it took for me to get on stage and nurture a voice influenced by ‘70s and ‘80s hard rock. My parents supported me in all other endeavors, but not when it came to singing in bands. At least I was getting to know my past self again; still, it was bittersweet consolation for the realization that some conversations could never be had.

I may have seen Jesus Christ Superstar to defy my parents, but it wasn’t defiance that made me fall in love with the movie, or with rock. I simply heard a sound that took me somewhere, the sound of that sinister guitar, and I had to follow wherever it led me. Just a budding rock chick in a Catholic schoolgirl uniform. Too little heaven on my mind. ◆

This piece is excerpted from the Fall 2023 issue of Parabola, SAINTS & SINNERS. You can find the full issue on our online store.