Time speaks in many voices, many different images and sounds. For the Neolithic builders of Stonehenge, sacred time was marked by the Summer and Winter solstices, particularly the Winter solstice, when, at around 3:50 pm the midwinter sun would set in the southwest and its rays flood through the center of the monument, dropping down onto the altar stone. Thousands of years later, for the medieval farmer time was the changing seasons and the saint’s days, as well as the monastery bells ringing out over the fields, marking the monk’s daily times for prayer, from matins to vespers.

Today we have atomic clocks that have an expected error of only one second in about 100 million years, but have little relationship to sacred time. For most of us time is no longer cyclical, but rushes us through the days, an ever-passing flow of moments and events. We have little relationship to the seasons of the land or even the seasons of our own life—the Seven Ages of Man, from infancy to old age, which Shakespeare describes as lived upon the stage of life1, and which was founded upon medieval philosophy and astronomy. For the ancients the planets were called chronocrators, or markers of time. It was presumed that different periods of life are ruled by different planets. For example, while Venus ruled the age of the lover, from fifteen to twenty-two, the final stage from seventy years on belonged to Saturn. But today time is no longer a natural unfolding, connecting us to the land and the cosmos, or the cycles of our life, but more often our own creation, driving us like a taskmaster, a treadmill going faster and faster.

Do we need to remain caught in this relationship to time? Is there a way to return to a sense of time that nourishes the soul and reconnects us to the natural world and the vaster cosmos? And more important, can we return to a sense of sacred time?

Beneath the thin surface layer of our present consciousness—a world of rushed days and time crushed into ever shorter segments—is the older world of the collective psyche, the archetypal world that used to be known as the domain of the gods. Here time moves more slowly, according to ancient rhythms. This is the home of Kronos, the primordial god of time, whose rhythm is like the movement of the stars across the heavens, a primal rhythm of the universe which contains the birth and the death of galaxies. And in the presence of this god is all of creation, each with its own time and yet part of a living whole—from the mayfly that lives for a day, to stars birthing and collapsing. Here the sunflower follows the sun each day, and here our ancestors worshipped, noting each solstice.

But we have locked away this god, just as we have separated ourselves from the ground under our feet. Rational consciousness has banished these rhythms and their sacred meaning from our daily life. “Father Time” is no longer present with his wisdom and deep understanding of the cycles of time, how they all interconnect, how the life cycle of seeds and the seasons mirror each other, how a bud breaking open in Spring and the leaves falling in Autumn sing together. Nor how our daily activities may be connected to the heavens, all part of a vast unfolding unity that belongs to the natural order of things, as was understood by the Chinese sage Lao Tzu:

Man follows the earth. Earth follows heaven. Heaven follows the Tao. Tao follows what is natural.2

In today’s world our telescopes may see the stars more clearly, but like the gods they are further from our daily life, their alignment no longer needed to determine propitious events. Time itself has also become stranded, isolated, no longer able to communicate, to share its ancient knowing. Because time is not just the passing of moments, but also carries the memories of the world—what has been written in the book of life. Like fossils in rocks, the memories of the Earth are held in the annals of time, what Theosophists call the Akashic Records. But we have long forgotten how to listen to this god. Instead we are stranded on the shore of our rational world, with our clocks and time passing, without fully understanding the world we inhabit.

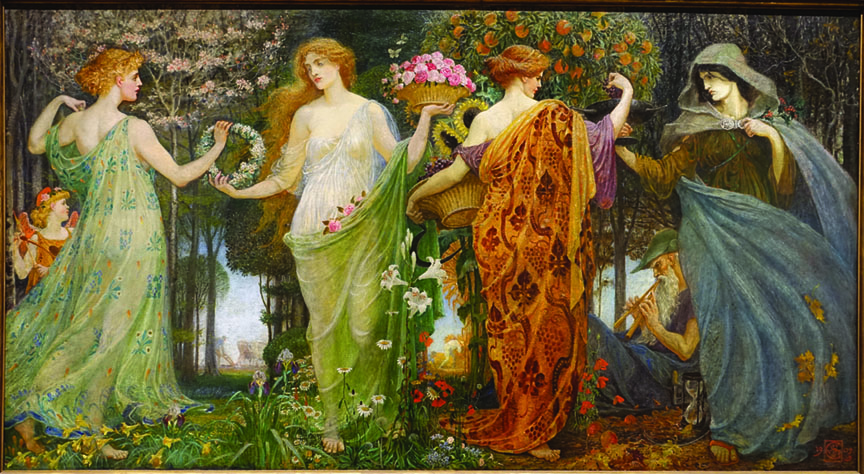

And time is not just an old man, but can also be imaged as a garden in which each flower has its place and meaning, everything tended with love. This is the secret of time: the meaningful flowering—the opening at the right time and in the right place, in the words of Ecclesiastes, “for everything there is a season and a time to every purpose under heaven.” In this garden each moment has its own purpose, its own part in an infinite pattern. In each moment of time a flower can open, an opportunity flourish, a synchronicity happen. But for this pattern to be realized, for its song to be heard, love needs to be present, this inner garden tended with care. When time loses the magic of love, or even a certain quality of attention, then a meaning is lost. Time becomes just the ticking of a clock.

Like so much today, we treat time as an object, even something mechanical, rather than a presence to love and respect. We may “watch the clock” but are rarely awake to the living presence of time. One of the unspoken tragedies of today is how time has lost its meaning, and the passing of hours, the unfolding of days, has become but a repetition, without substance or beauty, without fragrance.

These mysteries of the inner worlds used to be a part of our daily life, expressed in rituals and initiations. Initiations marked the seasons of our lives and linked together the soul and the body, made its transitions sacred. And when the corn was planted and then harvested with ritual, with prayer, we wove together the seen and unseen worlds. This is the land our ancestors walked, with a wisdom and knowing still held by Indigenous Peoples.

Now we have to find again the threads that can connect the moments of our lives to the patterns that surround us. Living in the midst of nature it is easier, as looking out of my window I can see the wetlands being filled by the flow of the tide from the bay. My day is marked by the rise and fall of the water, and the months pass with the arrival and departure of the birds on the shoreline, the seasons by the “V” of geese migrating high overhead. I have also reached an age in my life when time is less pressing, the demands of each day fewer. I can sit with the slower rhythms, how each Summer I wait for the young fawns to arrive, eating the grass, protected by their watchful mothers.

I used to have a mug I was given, on which was written “God put me on Earth to accomplish a certain number of things. Right now I am so far behind I will never die.” But now I am far from such lists of accomplishments, more often lost in a deeper silence that speaks to a different dimension of time. Here time and the timeless come closer together, often speaking the same language. I sense more and more how these two aspects of time are part of the same tapestry, just as form and emptiness mirror each other.

In today’s world the hectic, stress-inducing demands of time are often answered by the spiritual teaching that only the moment of now exists. And there is truth to this simple awareness of moment-by-moment existence. You can see it most easily in young children when each moment is lived for itself, those golden moments when the sun rises each morning for the first time, before time arrives, a world of clocks and calendars. This is also the mythical garden of Eden, a memory we carry within us of a pristine world before the Fall, before we became separate from the Source, when we walked together with God and everything was known as sacred.

But within each moment are also all the rhythms of time, the patterns that flow from this still center. Here we are part of the spiral of life, one of the first images of prehistoric art. The galaxies move in spirals like the sunflower and the flow of water. We live in the Orion Arm, a minor spiral arm of the Milky Way Galaxy. And the unfolding of time follows these archetypal patterns, each moment reaching back centuries and across space. Each moment is both outside of time and also contains time, for, as T.S. Eliot writes, “history is a pattern of timeless moments.”

Suffering from a poverty of the imagination we have placed time in a box, and then locked ourselves in this same box. We experience one dimensional time, just time passing. But time is alive in so many ways, from a moment-by-moment awareness to the rhythms of nature and the cosmos. Time dances to many different tunes, unfolds in different ways. It is alive in our stories and memories as well as the rising and setting of the sun. Even when we watch the breath, this moment-by-moment awareness, we are also present in time’s flow, oxygen entering the body with each and every breath, and then flowing out into our body and life.

And as we grow older we come closer to the mysterious intersection of timelessness and time. This is the garden we first knew as children, the “in the beginning” of our own story when play was joy. But now it beckons in a different way with the slowing of our body, with back pains and shortness of breath. There are more spaces in our days when nothing happens, when emptiness can be present, when simple things are more important than big plans.

We walk gradually to this water’s edge, allowing our consciousness to be touched by a different horizon. Often memories collect at this shoreline, sometimes like debris washed from a storm. Time then speaks differently, whispers of elsewhere. The journey continues, the journey always continues, but the signposts are unfamiliar, especially in today’s world that only values what is known and tangible. Our culture seeks to celebrate eternal youth, and even has frightening fantasies of immortality promised by AI. But if we are able to look and listen, to see the stories of time, we know that there is nothing to be lost, as in a Japanese death poem by Bairyu:

O hydrangea— you change and change back to your primal color

The rhythms of time, the seasons—the first frost on the ground or a bud breaking open in springtime—help us to remember we belong to the land, help us return to a place of belonging. But they also speak to the soul, so that it knows its place in this infinite unfolding. When the Neolithic farmers watched the mid-winter sun set through the great standing stones, something was aligned within the land, the cosmos, and their own soul. We may not know the language of this ancient connection. Even the consciousness of the medieval farmer who lived without clocks is too far away for us to fully comprehend, though the ringing of a monastery bell may stir the dust of more recent memories. But we can sense a world and a way of being that lives just below the surface, and reaches out to the stars. This vaster world of signs and sacred meaning we need to nourish us, to help us to find our way. Then time can once again be sacred and speak to us. ◆

1 “All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages…” From As You Like It.

2 Chapter 25, Tao Te Ching, trans. Gia Feng and Jane English.

This piece is excerpted from the Summer 2023 issue of Parabola,

THE COSMOS. You can find the full issue on our online store.