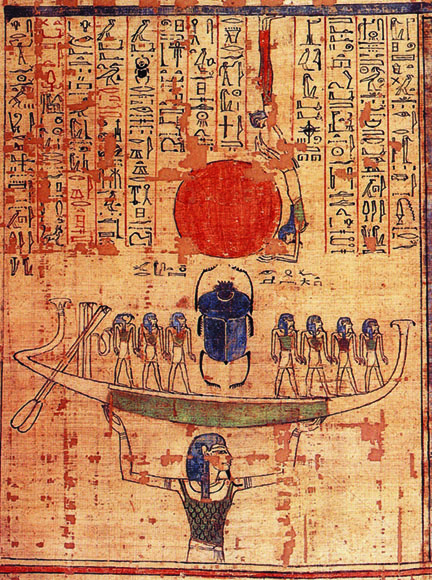

In the Kingdom of Egypt, when a mighty pantheon embodied the forces of nature, the elderly sun died each night and was born anew each morning. Lifted up from the underworld and carried across the nighttime sky by the winged scarab beetle, the glowing disk arrived at its appointed place on the eastern horizon. Far from lowly ovoid insect, the sacred dawn-bringing creature was Khepri, solar god and restorer of life, in guise.

Scarab and deity, reality and myth, nature and divinity, all were as one, all begged worship. With the breath of spirit flowing through and around them, the prerational inhabitants of the ancient world were participant-poets in a vital cosmic dance. Their prodigal offspring, Enlightenment observers, declined the spiritual inheritance and struck out alone, telescopes in hand, seeking fortunes of their own.

Silenced by the sophistication of a new millennium, Khepri vanished, leaving behind scarab amulets of precious stone on collectors’ glass shelves. Following him into the mists marched the parade of pagan gods and goddesses that once animated earth and sky. Traces of the era of enchantment lasted through the Middle Ages, when alchemists yet possessed the power to distill the elixir of immortality and transmute common lead into gold.

Philosopher and author Owen Barfield (1898-1997), a member of the Oxford Inklings—whose legendary members also included C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien—described our early ancestors’ perception of nature as “original participation.” In his book Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry, Barfield traces the shifting apprehensions of humans back to the earliest ages when virtually all phenomena were perceived figuratively and outer forms masked the true, heavenly essences concealed within. Animals and plants, wind and rain, sun and stars were comprehended not just allegorically, but as representations of the invisible world of spirit.

The ancestral connection to God—immersive, unconscious, creative, and communal rather than individual—was eclipsed by emergent consciousness and the intellectual study of the soul near 500 B.C. The teachings of Greco-Roman philosophers, great sages of the East, Jewish prophets, and Semitic minds converged to bring forth a new, systematic way of thinking and reasoning.1 A rare gift from the past—a memory of the original participating consciousness—has been preserved in the Hebrew language with the veiled meanings, symbolism, and numerical values of its letters and words.

As a philologist, Barfield viewed the history of words and language as “fossils of consciousness” providing clues to our psychic evolution. From the perspective of the original participant, whose world was simultaneously natural and supernatural, there was no distinction between the metaphoric and the literal. In The Rediscovery of Meaning, and Other Essays, Barfield notes that the word pneuma once meant both spirit and wind. By the seventeenth century, when humans came to reside within a well-defined material reality, a distinguishing line was drawn. In the newly compartmentalized cosmos, meanings became less subjective, delineating the split between inner and external reality.

The mythic, nonrational worldview all but fell away as French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’s philosophy of dualism severed mind from matter, observer from the observed. His use of reasoning to achieve understanding of the natural world laid the foundation for the empirical method of observation. Modern science would be grounded in objectivity, subjective experience consigned to irrelevance, and consciousness eventually reduced to the electrochemical processes of neuronal networks. Having separated themselves from the natural world they studied, even if the ghost of observer bias remained, Enlightenment thinkers explained phenomena in literal terms. Dealing in facts, they sought to discover the workings of the machina mundi, the machine of the world. As the quest for an evidence-based understanding of nature advanced, the fertile, imaginative world of myth that characterized the earlier age withered in drought, ushering in what Barfield called the “desert of nonparticipation.”

During the Age of Reason, transcendental visions gave way to scientific thinking and Isaac Newton’s precise equations describing motion and gravity. Mathematics was the language of God’s universe, suggesting that faith could be grounded in empiricism as well as Christ’s miracles. Three hundred years later, with the advent of quantum physics, we were obliged to reconsider the calculations that once neatly explained the observations: Newton’s gravitational constant is not a constant after all; measurements of time depend on frame of reference; a scarab is not solid matter. Down in the subtle subatomic realm, the beetle is composed, more than anything, of electron clouds.

As we extract more and more of nature’s secrets, physical reality takes on an uncanny resemblance to the illusory world of the ancients. The strangeness of quantum theory reignited the imagination of physicist and poet alike, yet contemporary culture still lives with the legacy of the mechanistic age. When natural philosophers began the process of dissecting the physical world, a priceless treasure began to ebb away. Like the Norse god Odin who sought to comprehend all that was hidden, we sacrificed an eye.2 Scientific knowledge yields riches, marvels of technology and longer lifespans, but at the same time it deprives us of essential meaning and our rightful place in the cosmos.

The lost connection to the Divine and attendant sense of alienation that came to plague materialist society registered deeply with the Romantic poets. Barfield embraced English Romanticism with its reverence for untamed nature, ancient folklore, and the perennial philosophy.3 The Romantics’ nostalgia for childhood emanates from the concept of preexistence and the soul’s closeness to God while awaiting birth. Edenic, innocent infancy progresses to pragmatic adulthood just as original participation progressed to nonparticipation. William Wordsworth laments his inevitable earthbound descent in “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.”

There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream, The earth, and every common sight, To me did seem Apparell’d in celestial light, The glory and the freshness of a dream. It is not now as it hath been of yore;— Turn wheresoe’er I may, By night or day, The things which I have seen I now can see no more.4

Wordsworth’s idealized view of childhood—untainted, connected to nature, imbued with fairytale magic— recalls the mystical perceptions of the ancients. Aside from this commonality, the Romantics emphasized the individual soul journey, not the shared. The cultures that lived among the old gods existed within a macrocosm, deriving meaning from collective, external experiences; the Romantic—and modern seeker possessed of an ego and well-defined sense of self—existed within a microcosm, finding meaning through private, internal experiences. The shift from experiencing God without to experiencing Him within was marked, in Barfield’s cosmography, by the birth of Christ.

Preparing the way for a new age, John the Baptist, self-exiled to the wilderness, urged repentance. Erudite Pharisees had set forth rules and laws for guidance, but the spiritual climate was one of aridity and the connection to God increasingly distant. Like Adam and Eve after the Fall, people felt a yearning for what was lost, but at the same time they had acquired freedom in the ability to think independently. Seeking knowledge, they began to gather at the synagogues, studying and praying rather than making rote offerings at the Temples and engaging in rituals.5

In the West, humanity’s moment of acute spiritual need coupled with an awakened sense of individuality coincided with the arrival of Christ, who addressed the crisis of separation and religious superficiality. Jesus conveyed the astounding message that God could speak directly to ordinary people, not only to the Pharisees, and that the Divine Father could be encountered within. His teachings showed the way out of nonparticipation and into full and conscious relationship with the Divine or what Barfield called “reciprocal participation.”

God had already inscribed the laws of Moses, the “do unto others,” in tablets of stone. Conveying a revolutionary message to the Israelites, Jesus advocated private prayer rather than public and stressed inner development over outer conformity to the law for the sake of propriety. Speaking in His native Aramaic, He instructed his apostles to pray to Abwoon or Abba, the “Our Father” of The Lord’s Prayer who was no longer a remote, unapproachable God. The possibility of awakening to kinship with our Creator and to the divine light within is made clear in the Last Supper discourse when Christ tells His disciples, “On that day you will realize that I am in my Father and you are in me and I in you”6 (John 14: 20).

Jesus taught that the “I am,” the indwelling Spirit of God, is accessible to each of us. We can reclaim our long-lost but inherent connection to the Divine, Barfield suggests, “If in Christ, we participate finally the Spirit we once participated originally.”7 With renewed participation, we cultivate spiritual intimacy with God, and at the same time we begin to recognize our own significance, our creative potentials and interconnectedness with one another.

This inner awareness engenders a sense of purpose and inspires creative invention, often expressed through works of art, literature and music—inner light reflected back to others. In The Rediscovery of Meaning Barfield references poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who regarded imagination, at its pinnacle, as the vehicle of “the divine creative activity of the logos,” the word of God. Barfield believed poetry, in particular, could help free us from the limitations of pure mechanical thought and open the door to higher perception.

When the words and metaphors of a poem are unfurled, symbolic meanings are released, dispersing insights that rouse intuitive wisdom. Through the imagination and the beating hearts of words, a poem becomes a bridge spanning from the world of matter to the world of spirit. Barfield’s view of an accessible, communicative spiritual realm draws contrast with C.S. Lewis’s rational Christian apologetics, but Barfield was not alone among the Inklings in recognizing the transformational power of the imagination.

Gathering in Lewis’s rooms at Magdalen College or at The Eagle and Child pub, the Inklings shared their ideas and unfinished manuscripts over pints. Some of Barfield’s views, namely those that overlapped with the spiritualist Anthroposophy movement, were regarded as idiosyncratic, even as friendships and mutual respect ran deep. Still, Barfield cast his influence on the circle of friends, as alluded in Tolkien’s consonant theory of “subcreation” where the artist mirrors, on a human scale, the creation of the universe. The artist does not conjure worlds out of nothing, but as one made in God’s image the artist brings “secondary worlds” to life.8 Like poetry, the art of fantasy evokes new realities, as The Lord of the Rings transports readers, via etheric state, to the land of Mirkwood elves.

Along with Tolkien, a host of subcreators have tapped the power of the imagination, conveying us beyond the mundane to those numinous states once inhabited by our ancestors. When we shift our perspective, the world is once again bathed in Wordsworth’s celestial light. For a moment we are in Norway, watching the flickering green flames of an aurora dancing across a dark night sky, listening to the wisdom of the indigenous Sami people, inviting Divine presence within, wondering at the sheer beauty of the cosmos.

Assuaging the soulless literalism of our age, the imagination re-enchants our planet Earth, brings the unseen into focus, reconciles mind and matter, inner and outer realms. Far from mere fabricator of fiction, this incomparable human faculty guides our exploration of the deepest meanings and mysteries of Faith and the natural world. As humans evolve through the century and ascend to a life of Spirit, Barfield’s last frontier, they will become light as mystics, one with all in an eternal dance among the stars. ◆

1 Rohr, Richard, Immortal Diamond: The Search for our True Self. Jossey-Bass, 2013.

2 Barfield, Owen, Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning. Wesleyan Univ. Pr., 1984.

3 The perennial philosophy originated with Renaissance thinkers and philosopher Marsilio Ficinco, who discerned a single truth and theology common to all the world’s religious traditions.

4 Wordsworth, William. “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.” The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1918. The Clarendon Press, 1939, p. 626.

5 Vernon, Mark. A Secret History of Christianity: Jesus, the Last Inkling, and the Evolution of Consciousness. Christian Alternative, 2019.

6 Ibid.

7 Barfield, Owen. Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry, Wesleyan University Press, 1988, p. 185.

8 Zaleski, Philip and Carol, The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings: J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016, p. 244.

The author thanks Laura Schmidt, Archivist at the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College, for her generous guidance through the Wade Center’s Barfield Collection.

This piece is excerpted from the Summer 2023 issue of Parabola,

THE COSMOS. You can find the full issue on our online store.