In my lifelong spiritual quest, I have read hundreds of sutras; plowed through pages and pages of philosophical texts; grappled with koan collections; analyzed thousands of poems; searched through biographies; meditated for hours; and interacted with many teachers, good and bad. However, I have gained the most from the contemplation, appreciation, and inspiration of the “ink tracings” of the great masters.

In East Asian culture, brushwork is considered a “mind seal”—a single stroke can reveal what is in a person’s heart. It can also express the essence of a master’s teaching. Since it is not the formation of the characters but the spirit behind the composition that matters, few of the most esteemed examples of brushwork were by professionals—and many masterpieces were by martial artists. In fact, Wang Xizhi, venerated as the greatest calligrapher in Chinese history, was a Tang dynasty general.

This book focuses on the brushwork of the budo masters of Japan. What defines a budo master? It refers to one who is well accomplished in all the technical aspects of the martial arts and, more importantly, the strategy behind warriorship. Strategy involves the ability to correctly evaluate an opponent’s strengths and weaknesses, both material and psychological. However, one can qualify as a budo master even if one never wielded a weapon or stepped on a battlefield. Although masters such as Takuan, Hakuin, and Sengai never touched a weapon as part of their Buddhist vows, they were as skilled as the best martial artists. Despite being frequently attacked by highwaymen, rogue samurai, irate daimyo insulted by criticism of their behavior, and a host of other miscreants, the masters emerged unscathed by getting out of the way, literally and figuratively.

In the fifteenth-century koan collection Shonankattoroku (no. 69), there is this example:

When her husband was killed in battle, Sawa became a nun to pray for her departed loved one. She shaved her head and entered Tokei-ji (the temple in Kamakura reserved for widows and divorcees), taking the name Shotaku. She devoted herself to Zen practice for many years, eventually being appointed abbess of Tokei-ji. One evening on the way back from a regular interview with her master at Engaku-ji, she was accosted by a would-be rapist. When the attacker threatened her with a sword, she immediately pulled out a sheet of paper from her sleeve, rolled it up like a sword, and thrust it directly at his eyes. He was unable to strike back, mesmerized by her intense energy. When he turned to run, she shouted a “Katsu!” so powerful it knocked him over. She then whacked him on the head with the paper sword. He got up and fled in terror.

Bodhidharma

[seal]

Niten

Niten, “Two heavens” (二天), is Musashi’s sobriquet.

In 2007, an exhibition titled Samurai was held at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. I had the precious opportunity to square off against this icon of martial artist brushwork by Miyamoto Musashi. In Japanese, the painting is known as Shomen Daruma (正面達磨), “True Face Daruma,” that is, “directly in front.” The gallery was not crowded, so I was able to assume a position before the painting with about a six-foot maai, the “combative distance” between two swordsmen.

I had a meeting of eyes with this Bodhidharma. The Patriarch’s gaze was penetrating, but it was not the lethal stare of a wild animal stalking its prey. Rather it was happo nirami (八方睨み), “a sharp look in all eight directions.” There was no hint of aggression; it was more, “Don’t even think of attacking me.” Bodhidharma’s countenance was severe but not grim. The brushwork was calm and settled, free of any suki, “opening,” in the composition. The lines of his robe were bold and confident. The painting seemed to be animate. In a real sense, I was encountering Musashi himself in the brushwork. It is one of the highlights of my life.

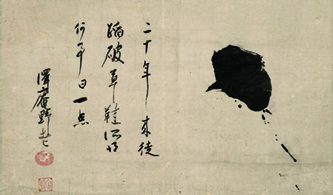

One-Word Barrier

ONE

After twenty years of wearing out countless straw sandals

What can you say to have gained? This one point!

Takuan, the rustic old monk

A “one-word barrier” is a single character, sometimes standing alone, sometimes accompanied by an inscription as we have here. In both Zen and budo, “simple is best.” One word is enough to capture the essence of a teaching. Here, the character (word) ichi is a dramatic splash of ink rather than the customary single horizontal stroke. “Twenty years of wearing out countless straw sandals” means to travel widely, internally and externally, for years and years to attain the one truth. Takuan wrote, “As you practice over the days, months, and years, you finally arrive at the point where you are not conscious of your stance nor hold of anything. . . . You are back at the beginning where you knew nothing” (Fudochi Shinmyo Roku).

The brushwork is unpretentious, composed in a natural rhythm; the sentiment expressed is encouraging, reassuring: “Sooner or later you will make it.” This is an outstanding work of art from any standpoint.

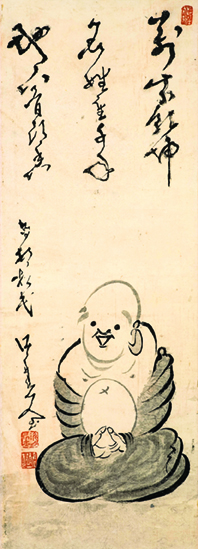

Hotei

From ancient times, throughout the universe,

His name is known for thousands of years:

[Hotei] revered on earth as a great being.

For Mr. Aramatsu, brushed by the old-fellow Deishu

Hotei is considered to be an incarnation of Miroku (Maitreya), the Buddha of the Future, who is always living among us, so we don’t need to wait until he makes his formal appearance millenia from now. Although dressed like a hobo, living free of social constraints, and doing want he wants, Hotei is actually a great bodhisattva, bringing Buddhism down to the marketplace. Deishu’s happy-go-lucky Hotei has a big smile on his face, despite his importance of being the future Buddha and the fact that he is doing zazen, usually thought of as a harsh discipline. This zenga shows us that Buddhism is not something abstract and distant; it is right here, manifest in our daily lives. It also shows that serious practice can (and should) be combined with existential good humor.

From The Art of Budo: The Calligraphy and Paintings of the Martial Arts Masters by John Stevens © 2022. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com ◆

This piece is excerpted from the Spring 2023 issue of Parabola,

TRANSFORMATION. You can find the full issue on our online store.