Parabola mourns the passing of Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, for many years a frequent contributor to our pages and the foremost modern translator and commentator of the Talmud.

To celebrate Rabbi Steinsaltz’s extraordinary life and achievements, here is an essay by Kenneth Krushel about meeting the Rabbi that appeared in our Winter 2018-2019 issue.

Preparing to meet in Jerusalem with Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz began, in retrospect, a year before in a working-class bar near Stockholm harbor, sitting with an anthropologist expert in Sami culture, drinking akavit between bites of pickled herring and crayfish. In Stockholm to present research concerning the Sami people’s use of Hebrew language teaching methods, the anthropologist was considering the question whether there is hope that the endangered Sami language would avoid extinction.

“Your question is not the right question, or at least slightly off kilter. The question is not one of linguistic revitalization. Your question is about the nature of hope and the accompanying paradox, the relationship between two disparate parts. Hope is a turning, the resolve to change one’s direction, the start of a connecting line, rarely a straight line, beginning with a question that leads to hoped-for realization. Hope is the anticipation that the bridge over the chasm will be crossed. Preserving an imperiled language is the destination on the other side of the bridge.”

Gesturing to somewhere beyond the window he said, “Just there in the harbor, four-hundred years ago, launched the most elaborate warship of the era. It was the hope of the king of Sweden that this flagship would intimidate Baltic and European maritime powers. Within minutes of launch, before royalty, aristocracy, admiralty, and shipwrights, the Vasa, as we are taught in school, top heavy with bronze canons, encountered a gust of wind and, dangerously imbalanced, capsized, sinking into the muddy bottom.

“See there, the massive building. The Vasa, rediscovered and raised after 333 years, is housed inside, a monument to sunken hope.

“Not far from this harbor, on Lidingöa Island’s cliffs, Sweden’s most famous sculptor, Carl Milles (1875-1955), searched for a landscape of subtle light and quiet. Go there. You’ll find the sculpture of hope.”

In the Millesgarden terrace is a sculpture of a human figure supported by a giant hand. This figure looks upward, fathoming some mystery, perhaps the roof of the sky. Milles knew of the Vasa and submerged despair. Here is The Hand of God supporting a man and man’s hope, hinting that what illuminates is not always in plain sight. This was one of Milles’s last works, a man looking skyward while precariously balanced, slightly turning to what is above, suggesting we contain the ability to wonder, a willingness to participate in meaning. A guide instructs a nearby group: “The hope is that standing upon the hand of God, we are not asked to bow our heads, or with self-satisfaction hold it high. The hope is that we hold our head erect and see ourselves.”

The tour departs and what remains is something rehabilitating, atmospherically humble and unpronounced. The man in The Hand of God is communicating self-disclosure, a hope reverentially held aloft, revealing the possibility of what can be in contrast to the person one has been.

How to begin a conversation about the “meaning of hope” with Rabbi Steinsaltz, among the most renowned Talmudic scholars of the era? This interviewer’s hope arises out of the uncertainty that the questions introduced will invite wisdom as a reflection and extension of the rabbi’s life’s work and purpose.

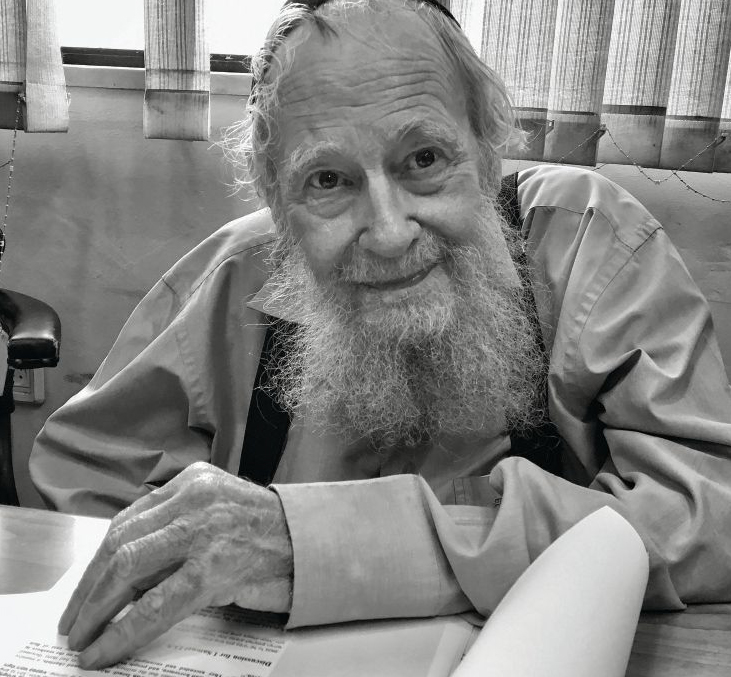

He is a teacher, philosopher, social critic, and mentor cited by Time magazine as a “once-in-a-millennium scholar”. His work had introduced the Talmud, Judaism’s central text of law, ethics, heritage, and history, beyond the confines of yeshiva.

In addition to writing some sixty books on theology, prayer, zoology, and mysticism, with a few mystery novels included, Rabbi Steinsaltz has taught throughout the world. He has been the recipient of a multitude of prizes, tributes, and accolades from world leaders and inspired an international organization that extends his work and Talmudic study globally. In 1988 he was awarded the Israel Prize, the country’s highest honor.

Rabbi Steinsaltz is strictly Orthodox, but unlike many prominent rabbis in Israel today, he avoids center stage and extreme ideological pronouncements. Cultural exclusivity is not in his vocabulary. Today, at eighty-one years of age and despite having recently suffered a stroke, he works daily in his Steinsaltz Center study. The center is the focal point of the worldwide activities and initiatives inspired by Rabbi Steinsaltz. The list of the center’s visitors and speakers showcases his radical pluralism: poets associated with the ‘Mizrahi struggle’ against cultural and political discrimination, professors who are considered off-the-charts left-wingers, a rainbow of male and female rabbis, a Knesset minister whose central dogma is allowing Jews to pray on the Temple Mount, and an Arab journalist.

Although his family was secular, his communist father insisted he study Talmud, wanting his son to be an apicorus (heretic) not an haMaretz (ignoramus). While studying chemistry and physics at Hebrew University, he delved into Jewish studies, and after graduating founded a cheder [school] and the Israel Institute of Talmudic Publications, beginning his life’s work: taking forty-five years, he translated the Babylonian Talmud from its original Aramaic into modern Hebrew with commentary accessible to a layperson: the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud, now translated into English, Russian, and French.:.

Across the narrow street from the Steinsaltz Center is a modest park, a convenient place to sit and prepare. With a trace of panic I flip through notebook pages crammed with epigrams having to do with hope. The abundance of conflicting philosophical insights seems something of a centuries-long chess match among philosophers:

Early Greek thought: Hope results from insufficient knowledge, and the influence of wishful thinking. Hope results from self-hypnosis.

Greek mythology: As all that is evil and malevolent escape Pandora’s box, but Elpis (the embodiment of hope) remains in the corner shadows of the box. Why? To keep hope from man? To preserve the potential of hope for when it is needed?”.

The Stoics considered hope as intertwined with fear. Seneca writes that hope is seen as an extension of suffering.

Augustine and Aquinas considered hope as a central virtue of the true believer, justifying action not bound to knowledge

Spinoza explains that hope is essentially irrational, a cause of superstition, the basis of political power, the result of false belief, belonging “to a mind in suspense, to a mind in a state of anxiety…”

Nietzsche sees that hope is an expression of misguided relationship to the world, unable to face the demands of human existence.

Kierkegaard comments, “The value of hope depends upon its relation to love. We hope for ourselves if and only if we hope for others, and only to the same degree…A person’s whole life should be the time of hope.”

The mind wobbles, but it is now time to meet Rabbi Steinsaltz.

I climb the Center’s stairs and push the button by the entry. An intercom voice: “Who is this?”

Soon the door opens, the rabbi’s assistant Amitai Zuriel offering greetings, but with an expression combining distraction, apology, and concern if not alarm.

“The rabbi is not here. The was a schedule mishap.”

The calendar confusion is sorted out and an invitation extended for the following week. I leave behind maple syrup that my family produces and bottles. The label’s graphic is of Carl Milles’s sculpture The Hand of God.

Rabbi Steinsaltz comes to his study every day and edits his work, a process of subtracting, deleting what is superfluous, even commas. A life of extraordinary study in scale and scope, and voluminous writing , and now in a state of subtraction. He is not adding to an edifice, but stripping bare the foundation like some archaeological dig. His hope is to uncover increasing clarity.

The following week, entering the rabbi’s study, I meet a diminutive, wizened figure, who looks directly at me with luminous blue eye that are anything but diminished. Rabbi Steinsaltz has talismanic eyes and an expression of calm. He reaches his hand, extending an index finger, which I grasp. Because of his stroke he has difficulty speaking.

Amatai encourages me to speak, to lead the discussion.

I have prepared a plan: a brief self-introduction, explain the purpose of this meeting, request permission to use an excerpt from his writing, express gratitude, exit. The plan is discarded as soon as I see the opened bottle of maple syrup on his desk aside a cup of tea. Using a cell phone I retrieve digital images of the majestic maple trees, more than a century old beauties, captured in the setting amber sun of northwestern Connecticut, now less than a world away. The ensuing unrehearsed soliloquy describes these trees that produced this very maple syrup. It is generally, and inaccurately assumed that maple sap flows up from the tree’s roots on warm days. But on warming (above 32 degrees) late winter days following cold nights, sap flows down from the maple tree’s branches, dripping out through spiles into buckets, then boiled in an evaporator. The internal pressure of the tree, when it is greater than the atmospheric pressure, causes the sap to flow out much the same way as blood flows out from a wound. It is nature’s circulatory system.

The tree photos are revealing details even more real than I ordinarily see. The rabbi is accepting my truth. His face suggests the utter and unashamed absence of masks. Although he is not verbalizing a response, Rabbi Steinsaltz talks with his hands and eyes, molding the clay of abstraction into something immediate and present. His life’s work, his words, have offered weight and volume, existing and struggling with the complicated idea of truth and its shades of meaning. He works to present the reality of a living truth rendered in the words of a living tradition. The rabbi motions for me to come closer and points to the bottle.

He is pointing to the label, Carl Milles’s sculpture on the cliffs, near the harbor where all hope was submerged for some three-hundred years. I wish to avoid clichés; I hope I am not stumbling into an uncustomary innocence. “Man, in ‘The Hand of God’,” I explain and because the rabbi is so fully present there is no handcuffing my hope that I am connecting with the rabbi. He listens, turning into the spoken words, not unlike the sculptured figure.

Before departing I read a passage from The Thirteen Petalled Rose,” the rabbi’s “discourse on the essence of Jewish existence and belief.” The excerpt is about teshuva, a “return,” a turning about, or “turning to.”

“It is the self-obliterating view of oneself that provides the true basis of all existence, that makes possible a firm grasp of the truth of reality. For then the circumscribing immensities of existence take shape in one’s understanding, and it becomes apparent that one is a part of them….

“One becomes conscious of a vast arc, curving from the divine source to oneself, which corresponds to the question: Where do I come from? While at the same time a line curving from oneself to Him corresponds to the question, Where am I going?”

He listens to the request to use his writing on Teshuva as a source for an article on hope. His expression suggests something obligatory to human searching of perception, something of the greatest stature, and also vulnerable and fragile. He says, “Yes.”

The Indo-European root of the word hope comes from the stem “k-e-u,” the same root for the word “curve,” a movement in a different direction, a bend without angles, a capacity the Vasa lacked.

Rabbi Steinsaltz writes of teshuvah as meaning “repentance,” from the root meaning “to turn.” He explains that teshuvah denotes a turning about, a response, a curve, an arc, as shown in the following passages from his book Teshuvah.

The Essence of Teshuvah

Teshuvah’s starting point is rooted in the point of transition from the past to the future, the path of the past and adopting a new path for the future. Teshuvah is simply a turning, be it a total change of direction or a series of many separate turning points.

Three times a day, a Jew petitions for teshuvah and forgiveness. The meaning of this repetition is that each petition indicates the possibility of some kind of turnabout. The more settled and tranquil a person’s life, the less sharp a turn he is likely to take. Yet, often, when a person reflects on his actions in retrospect, he realizes what the important turning points in his life were, even though he did not notice them at the time.

Feeling the Need for a Change of Direction

Two factors make this turning possible: the recognition that the past is imperfect and in need of correction; and the decision to go a different way in the future.

The recognition of the need to change does not always come in the same way. Sometimes one is overcome by a sense of sinfulness that burdens the soul, resulting in a desire to escape and to purify oneself. But the desire for a turnabout can also come in more subtle forms leading to a search for things of a different nature.

The more acute the initial feeling of past inadequacy, the sharper the turnabout is likely to be, sometimes to the point of extremism and complete reversal. The inverse is also true: When the feeling of uneasiness about the past or present is more subdued, the resulting turnabout will generally be more moderate, both in pace and sharpness.

Whatever the initial feelings about the past, the desire to do teshuvah always springs from a clear sense of unease about the status quo and the past.

Obtuseness of the Heart

The greatest obstacle in the way of teshuvah is self-satisfaction. One who is pleased with himself feels that “everything is okay” as far as he is concerned, and that if reality is flawed, the flaws are common to all human beings, to society, to the family, to God, etc.

Commitment for the Future

The second component in teshuvah is called “commitment for the future”–the resolve to change one’s direction from now on. This is the natural continuation of the first step in the turnabout, and its force, direction, and staying power largely depend on the clarity and strength of the initial feeling about the past.

One who feels uneasy and characterizes his uneasiness with the words “not good” does not necessarily come to the decision to change, let alone change in practice.

On the other hand, the very fact that a person regrets his actions and feels his inadequacy, does not necessarily guarantee the desired outcome either. Instead, it can lead to a deepening sense of despair, the loss of hope, and a fatalistic resignation to the status quo without any attempt to change the situation.

Thus, remorse in itself, for all its decisive initial importance, must be accompanied by hope and belief in the possibility of change. In this sense, teshuvah is one of the foundations of man’s hope and reawakening. The awareness that the door is always open and that there is always a way to teshuvah can serve as a stimulus that creates the possibility of teshuvah.

A Path both Long and Short

Teshuvah is a world unto itself, embracing two apparent opposites, not contradictory but complementary.

In one respect, there is nothing more difficult than doing teshuvah, because teshuvah means transforming oneself. In another respect, there is nothing easier than teshuvah; a split second of turning is already considered teshuvah.

The ba’al teshuvah (penitent) is thus like a person following a certain course who in an instant decides to change direction. From that point onward, he no longer goes the old way, but a different way. Yet the new path, like the old one, is long and unending.”

As the story of maple syrup is shared with Rabbi Steinsaltz it seems to me that, for this instant, hope is enveloped in every force and hidden chance in the universe. My words, which ordinarily I would consider anchored in matters ordinary and obvious, now convey hoped-for meaning, sharing the particular phenomenon nature offers–the maple’s tree alchemy–with something exact and yet whose mystery is beyond designation of words.♦

From Parabola Volume 43, No. 4, “Hope,” Winter 2018-2019. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.