“If I were God, I’d forgive the whole world.”

Robert Bresson, L’ARGENT

Three years ago, just before I started shooting my first fiction film, I found myself reading and re-reading a collection of essays by Flannery O’Connor, a writer I hadn’t returned to since I was in my twenties. In that collection is an essay called “Catholic Novelists and Their Readers,” assembled after her death from drafts of a lecture she delivered on the titular subject. O’Connor deals with the question of fiction written for and marketed to “typical” mid-century American Roman Catholic readers. On The Foundling, written by none other than Cardinal Spellman himself, she is merciless. “You do have the satisfaction of knowing that if you buy a copy of The Foundling,” she writes, “what you are helping are the orphans to whom the proceeds go; and afterwards you can always use the book as a doorstop.” As for the many less innocuous “Catholic novels” then on the market, she makes even shorter shrift: “…these are novels that, by the author’s efforts to be edifying, leave out half or three-fourths of the facts of human existence and are therefore not true to the mysteries we know by faith or those we perceive simply by observation.”

It was the following passage, though, that really struck me. “St. Thomas Aquinas says that art does not require rectitude of the appetite, that it is wholly concerned with the good of that which is made. He says that a work of art is a good in itself, and this is a truth that the modern world has largely forgotten. We are not content to stay within our limitations and make something that is simply a good in and by itself. Now we want to make something that will have some utilitarian value. Yet what is good in itself glorifies God because it reflects God. The artist has his hands full and does his duty if he attends to his art. He can safely leave evangelizing to the evangelists. He must first of all be aware of his limitations as an artist—for art transcends its limitations only by staying within them.”

I read these words for the first time in a quiet empty chapel at the east end of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Then I did two things that I often do: I transcribed them in my notebook, and I shared them with Martin Scorsese. Who had, as it turns out, been reading O’Connor’s letters at the same time.

Marty and I have known each other for almost three decades, and I wasn’t at all surprised that he was reading O’Connor. I didn’t wonder if he would find the quoted passage interesting. I knew he would, because he lives those words.

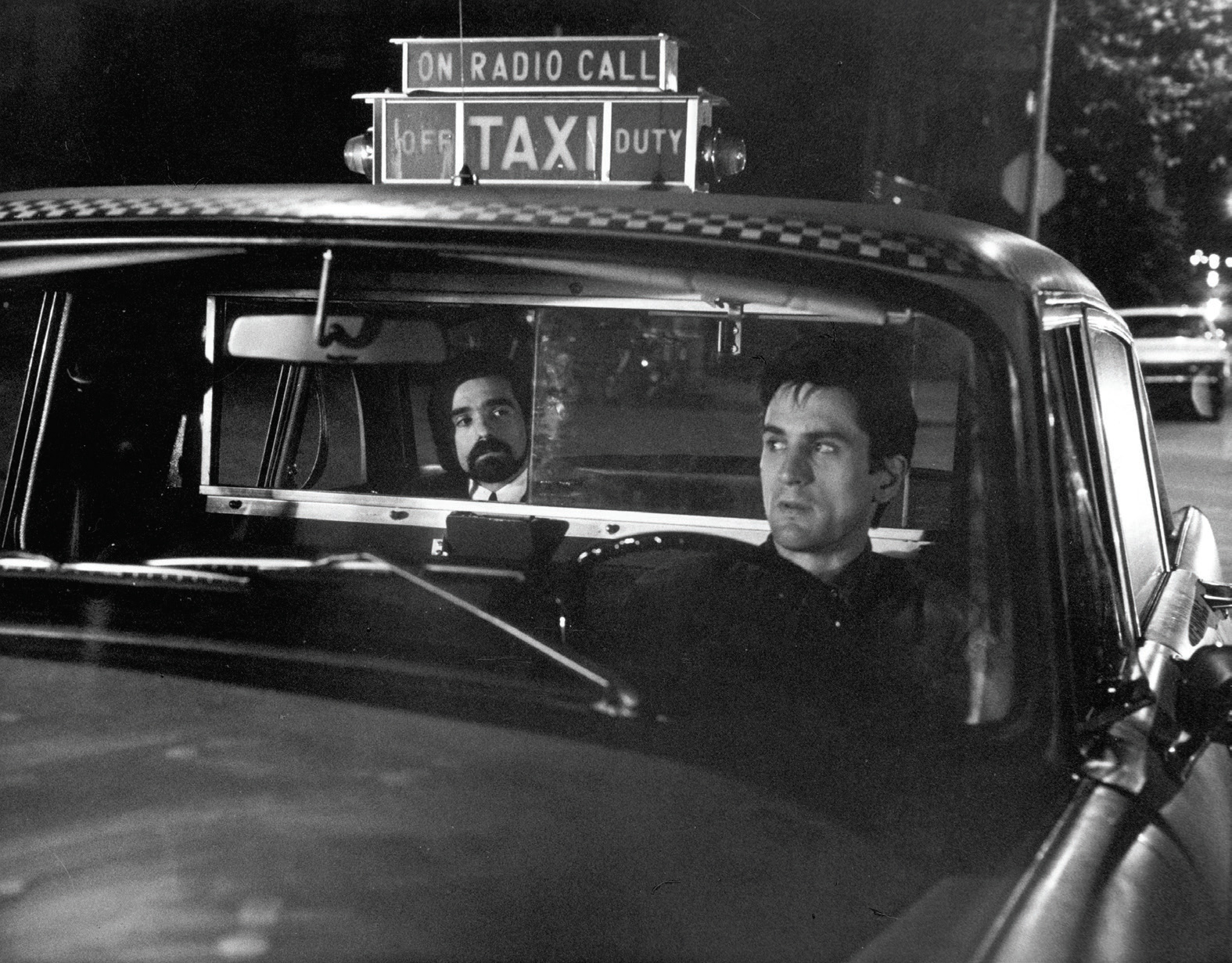

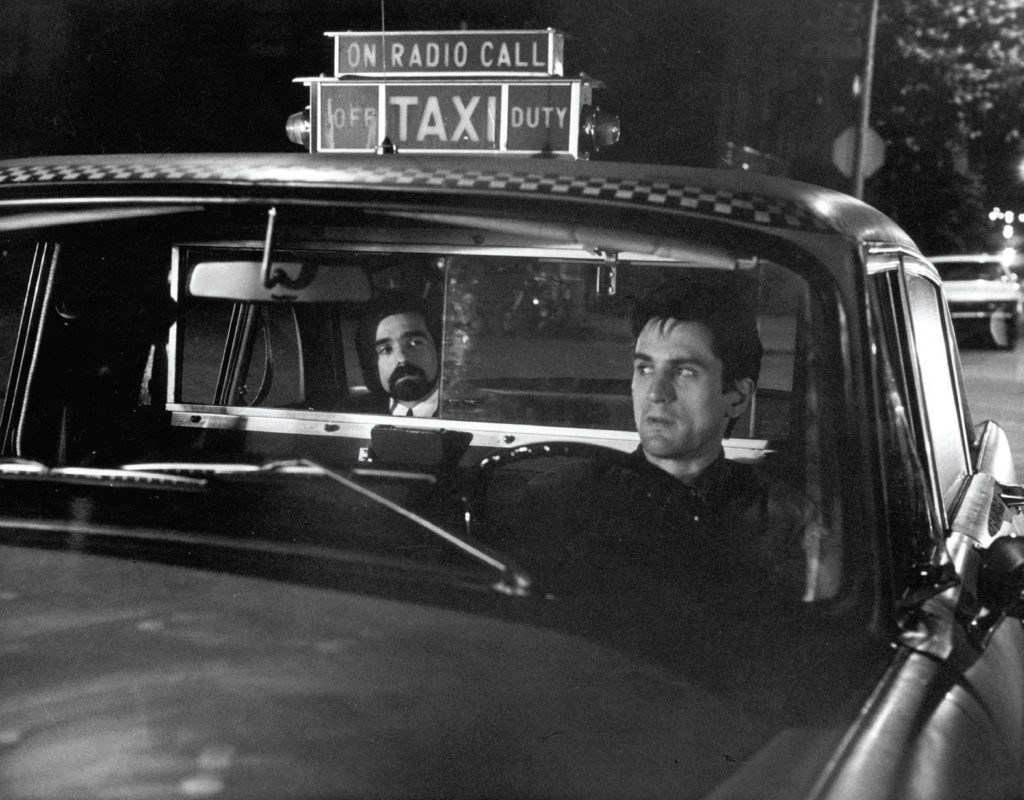

In 1977, the great French director Robert Bresson was interviewed by Paul Schrader for Film Comment magazine on the occasion of his most recent film, The Devil Probably. “The young man in my film is looking for something on top of life, but he doesn’t find it. He goes to church to seek it, and he doesn’t find it. At night he goes to Notre Dame, to find God, alone. He says lines like this, ‘When you come in a church, or in a cathedral, God is there’—it is the line of his death—‘but if a priest happens to come, God is not there anymore.’ This is why, although I am very religious—was very religious, more or less—I can’t go to church in the last four or five years when these people are making their new mass. It is not possible.” Bresson’s film ends with his spiritually bereft hero committing suicide—a mortal sin. At the time of the interview, Schrader (raised in the Calvinist Christian Reformed Church) had just shot his own first feature and before that had written Taxi Driver, which is indebted to Bresson’s Pickpocket and Diary of a Country Priest and which ends with a mass murder committed in the name of a grand delusion of divine rectitude.

I was a teenager when Taxi Driver came out, and I saw it somewhere in the neighborhood of fifteen or sixteen times in the local theater and then at the drive-in. The topic of bloodshed on the big screen was red hot in those days, and one got used to hearing and reading that movies like Taxi Driver were having a “negative influence” on the culture. To experience the actual film, as opposed to the Cultural Conversation piece, had nothing to do with frozen “concepts” or “ideas,” the trafficking of which has increased a thousandfold in the forty-plus years since. Of course, there were films that did nothing but traffic in the latest “issues” and “ideas,” and there are many more of them now—they are, in fact, not so much films as arrays of “culturally resonant” touchpoints illustrated with moving images that are then assembled in beguiling and occasionally scintillating patterns. Some of them win multiple awards.

Taxi Driver, on the other hand, like Mean Streets or Raging Bull or Casino or Silence or The Irishman, is made, in the sense that O’Connor defined. Like any real work of art, it traffics in nothing but its own immediate materials and touches on matters of cultural concern only incidentally and as a consequence of deep engagement with the shared ongoing world. One can take a stab at naming and elucidating its themes, but such descriptions will always remain provisional, simply because the film is true only to itself. It grows organically from a felt sense of life. This is what William Carlos Williams meant when he wrote that the aim of any artist should be not to copy nature but to imitate it. To copy is to remain safe in the realm of appearances. To imitate the processes of nature is to act, and to delve into the heart of our mystery.

For that reason, there can be no such thing as a great Catholic film or a great Calvinist film or a great Buddhist film. To set out on such an undertaking is inimical to the work of the artist. “We Catholics are very much given to the Instant Answer,” wrote O’Connor, and the same could be said of many organized religions and spiritual practices. “Fiction doesn’t have any. It leaves us, like Job, with a renewed sense of mystery.”

As it was for O’Connor, Marty’s need to see, to make, to transmit was intensified and purified by illness—in Marty’s case, asthma. “I was allergic to everything around me, including animals, trees, grass—everything,” he told me during a conversation that we recorded for another purpose a few years back. “I could not go to the country. They would always have to take me back that night or the next day. The humidity…and the pollen… But what it was, was that it separated you from everybody. And it made you aware of an adult world in a way that was…quite unique. You spent a lot more time with the rhythm of that life, with the concerns of the adults—you were privy to all the discussions, what’s right and what’s wrong, whose obligation this is or that is. And it just made you more aware—aware of how the people were feeling, what the body language around you was, aware of your own sensitivity. You became sharpened, I think. Yet, in making a film, you can be extremely insensitive, too. But within that determination that you need to actually make a film, you incorporate that sensitivity.” Determination, sensitivity, and solitude.

I remember sitting in the living room as a child with my parents, transfixed by a movie showing on television. My parents watched and they also went on talking, asking if this or that actress was alive or dead, what was the weather supposed to be like tomorrow, and “could you go to the kitchen and get me a Fresca?” Marty had the same experience. “For everybody else, it’s just another ‘movie,’ and meanwhile, for you…it’s life and death up there.”

That’s the great paradox. To know what you love, to know what you want to extend and transmit to the world because something has been transmitted to you through art and created a spark, is to know loneliness and real solitude, because no one else can share it. But it is also to know the deepest love for those around you and the world they’ve created. To become attuned to art is to become attuned to the pure sensation of being alive, because you are seeing it embodied in all its mystery.

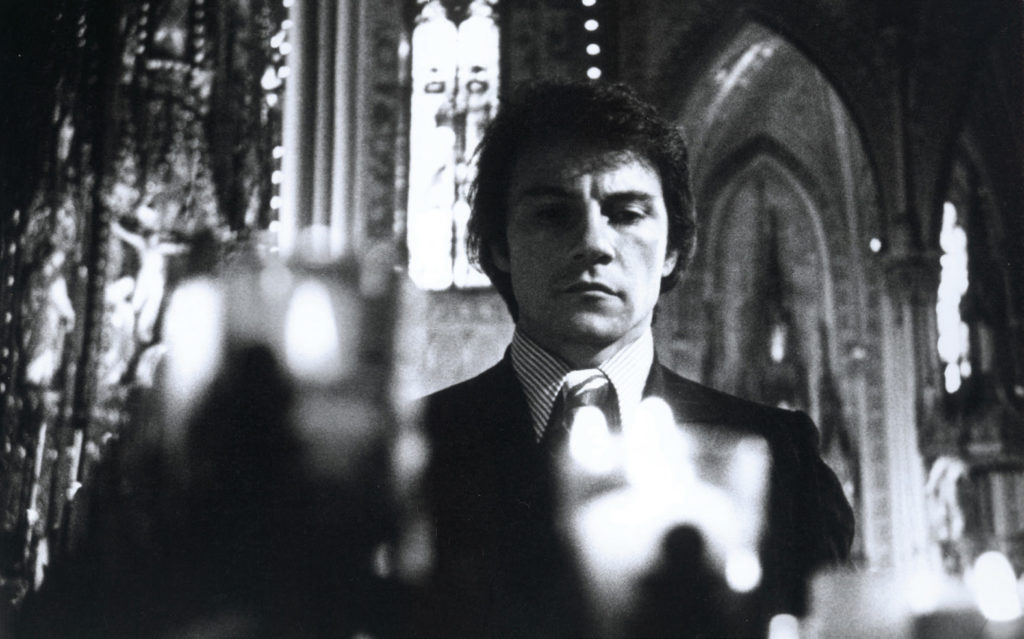

Marty was drawn to cinema and to the church, simultaneously. “The profound impression of Catholicism at a very early age is something that I’ve always related back to,” he said. “One may read or become interested in many different ways…I’m interested in how people perceive God, or perceive the world of the intangible—all people, everywhere. But my way has always been through Catholicism.” Within the world of Little Italy in the 1950s, many of the elements that are constants in Christian sermonizing were immediately and tangibly present. The “least among us” lived in the shadows of the Third Avenue El and in the bars and missions and flophouses on the old Bowery. The “criminal element,” as it was called, cast a different kind of shadow over the neighborhood, and violence and tenderness and beauty existed in very close proximity. The priests at Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral dealt with the world around them, now long gone, as it was. “I was very aware as a child of a God of storms and lightning and punishment, and then it was balanced by these priests, who showed me another side of it. Their words were one thing, but their actions were something else entirely. They were street priests—Diocesan priests. They didn’t force you to do things. They cajoled. They may have been very strong in their language with you at times, and they would lecture you about the wages of sin and impure thoughts and so on, but there was an extraordinary love. It was an amazing experience.”

The priest that had the most profound effect on Marty was Father Principe, who passed away last year in his nineties. He can be seen in the PBS documentary Martin Scorsese Directs, made around the time of GoodFellas. His presence is as straight and swift as an arrow. “I wanted to follow in Father Principe’s footsteps, so to speak, and I went to a preparatory seminary but I failed out the first year. Because I realized at age fifteen that a vocation is something very special, and it can’t be because you want to be like somebody else: you have to have a true calling.”

There could also be a calling to do something else, namely cinema, and of that Marty has spoken for many years and under a variety of circumstances with great eloquence. Those are words of inspiration, but they are also words of caution to anyone who imagines going into a “career” in filmmaking the way one would go into a career in law or business. It is possible, he is careful to remember, to become a “professional” director. To be a filmmaker is something else again.

In the mid-1960s, just as Marty was starting to make his own first feature, the country was flying apart at the seams and he began to question his own relationship to Catholicism.

“I was changing and I didn’t know if I was going to become mature in the religion. Vietnam was declared a holy war, and there was a great deal of confusion and doubt and sadness for the whole country, and for me. So seeing Bresson’s film version of Diary of a Country Priest at that time gave me hope. The characters in that film are really suffering, and they’re being punished, by others and by themselves, throughout. And at one point, the

priest says to a woman in his parish, ‘God is not a torturer—He just wants us to be merciful with ourselves.’ And I thought: that’s the key. Even if we might feel that it’s a punishing God, a torturing God, we have to remember that we’re the ones doing the torturing, so we’re the ones we have to be merciful with.”

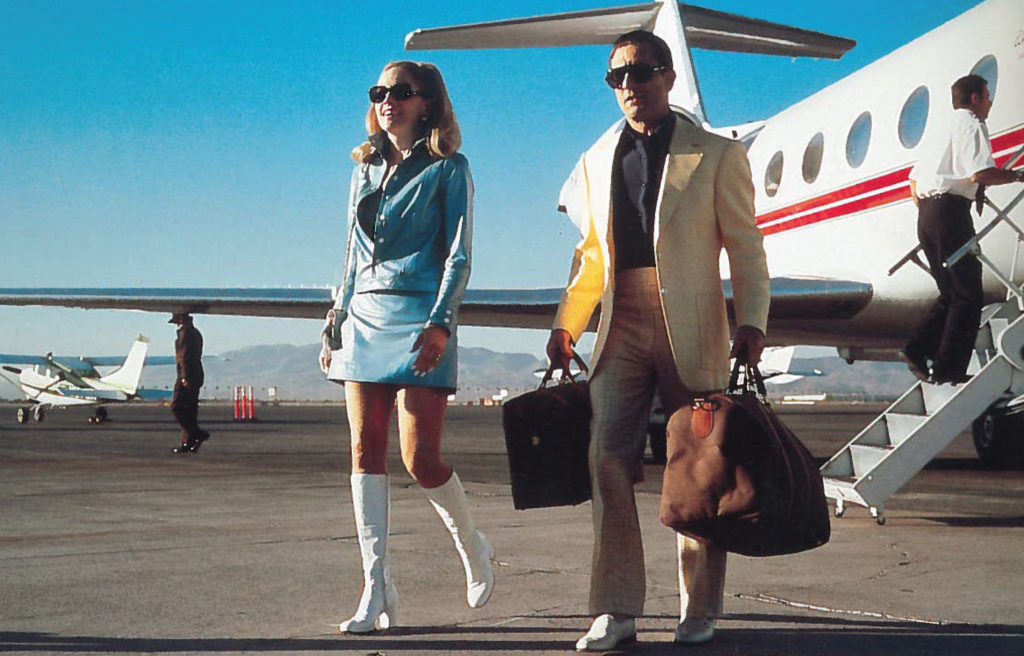

It’s impossible to singularize the work of an artist, to summarize his or her preoccupations. However, I think that it’s just to look at Marty’s work through the lens of mercy. He has made many films about people who torture themselves with delusions—delusions of cheap grandeur, as in Casino and The Wolf of Wall Street; delusions of ease and comfort and misplaced certainty, as in GoodFellas and The Age of Innocence; spiritual delusions, as in Mean Streets and The Last Temptation of Christ and Silence. These delusions are intensified versions of the same delusions from which we’ve all suffered. The manner and pace of human change in those films is properly aligned with lived life, which is precisely why these characters who commit the worst imaginable actions radiate humanity: for them, mercy is either out of reach or unthinkable, but it is always present, even as a felt absence. The characters in these films believe that they can not be kind to themselves or to each other because they are in the thrall of grand dreams and even grander misunderstandings of rectitude, fairness, and retribution carried over from some earlier moment in their lives. The majestic unspoolings of excess (in GoodFellas and Casino) and extravagance and ceremony (in The Age of Innocence) and wild flights of craziness and cruelty and group euphoria and violence (in Mean Streets and Taxi Driver and Raging Bull) resonate so deeply because they’re framed within impermanence and instability—the characters fail to recognize their circumstances but we feel them in the rhythm of the storytelling, in the sudden yet tender seizing on small homely details (like the cuts to the coffee cups in Raging Bull or the stray faces in Mean Streets, or the move into the garish Christmas tree ornament in GoodFellas) that will soon be lost forever. Somehow, they carry and transmit a possibility: forgiveness and redemption are always just around the corner. This is what gives the movies their throat-catching poignancy.

Right before Marty and Robert De Niro were set to start production on Raging Bull, they had a meeting with the new executives at United Artists. One of the execs asked them why they wanted to make a movie about Jake La Motta. “The guy’s a cockroach,” he said. De Niro’s response was simple: “No, he’s not.” Raging Bull poses a question to its audience: how can someone who cannot articulate the terms of his own humanity find his way to it? The answer is in his own being, his very presence, and in the presence of the world around him. The answer is in those coffee cups, and in his brother gently tucking his hair under his hood before he walks to the championship bout, and in the laying of hands he observes so suspiciously between his brother and his wife and the mob boss who comes to visit as he prowls his Detroit hotel suite in a black polo shirt that electrifies the screen.

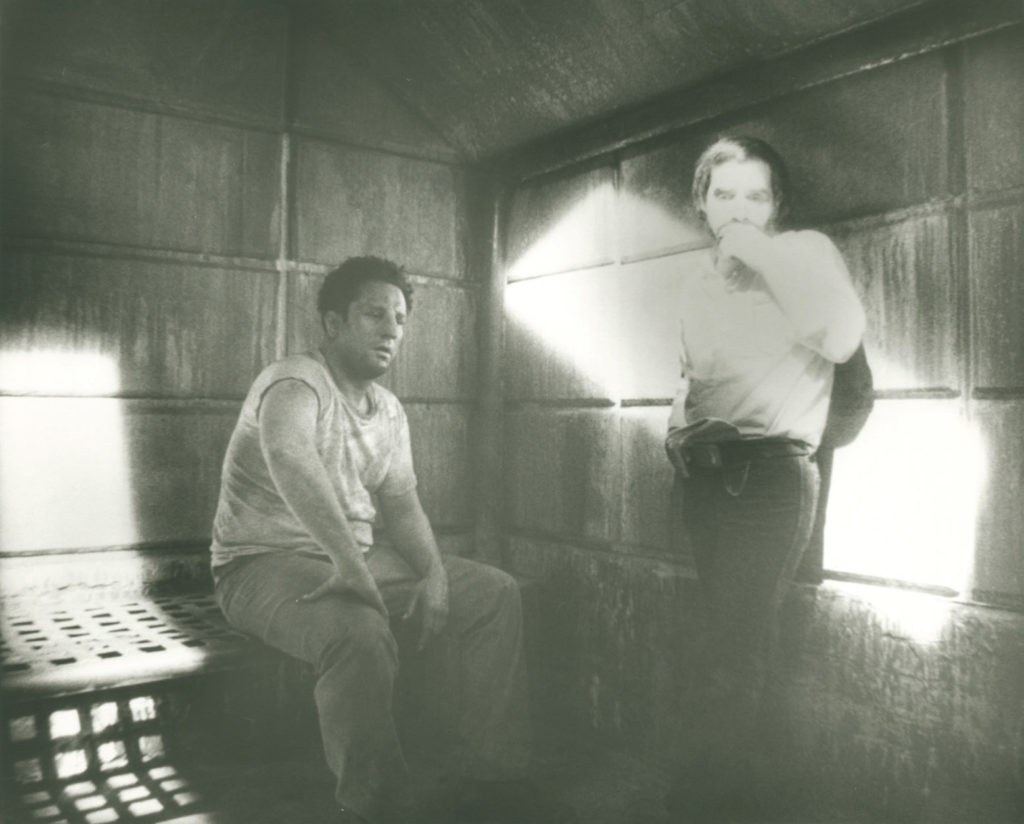

I was twenty years old when Raging Bull came out. I skipped school to see it with my best friend on the day it opened in New York. I was stunned and so was he. And perhaps a little puzzled at first, because I’d never seen anything like it. I still haven’t. And I took in the film on a physical level, which is as it should be. When Jake La Motta finds his way to forgiveness, he literally comes up against a brick wall, in a Miami jail cell. Out of anger at his jailers and anger at himself—in the end, one and the same—he tries to beat his way through the walls, with his fists, his forearms, his head, until he finally comes to a stop and is able to say the simple words: “I’m not that bad.”

“In Raging Bull, he’s the one who has to stop punishing himself,” Marty told me. “Yes, he’s punishing everyone else around him at the same time, but he has to start with himself. And at the end, when he looks in the mirror, he’s found a way to start finding some mercy for himself. You gotta face yourself. The problem is actually forgiving yourself. It’s hard. Many people can’t even imagine it. And…maybe the word ‘forgiving’ is pompous…accepting yourself is what it is. Living with yourself. Because that might make it easier to live with other people, and be good to other people.”

As Thelma Schoonmaker, who edited Raging Bull and every one of Marty’s narrative films since, once put it to me, “Raging Bull isn’t a movie, it’s a poem.” It’s a poem of mercy, the road to which is paved with horrible violence, jealousy, paranoia, loss, but also fleeting beauty and abiding love. And it could only have been composed by artists with a fierce and binding commitment to the least among us…and within us. “The practicing is not in a building where you meet at a certain time on a certain day of the week to perform certain rituals,” observed Marty, in an echo of Charlie’s first words in Mean Streets (spoken in voiceover by the director himself). “The practicing is outside, and it’s really everything you do, good or bad. And that’s been the struggle. It’s in your actions, and how you relate to the people around you. It’s not necessarily a matter of the good that you create, because you might think that you’re doing what is good for others when actually you’re not. Maybe you’re just placating your own conscience, you know? There’s also the damage one does. So the way that religion and spirituality play out is in your behavior with others. After everything that’s happened in history, after all the ways the world has changed and been overwhelmed by thought, political and economic theories, different systems of governing, different systems of belief…it always comes down to the person in the room with you. That’s really what it is. And whether you’re successful at it or not, it’s in the trying. It really comes down to that. And this has been, for me, over the years, very difficult because of my absorption in work. Because I express it in film.”

We all pray that the people around us will be able to forgive themselves. We diagnose the struggles of others so easily, and we are shocked when they see and name our struggles. To forgive, or to accept, is to see—everyone and everything, including ourselves. One must work to see. And one begins the work by learning to recognize the difference between that which momentarily intrigues, or that which promises much and delivers little, and that which actually illuminates. This is what I recognized in Mean Streets when I saw it for the first time, forty-six years ago, and in so many films and loving gestures since. ♦

From Parabola Volume 44, No. 3, “Mercy & Forgiveness,” Fall 2019. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing. Four times a year Parabola has explored the deepest questions of human existence. Without your support, we would cease to exist. Please consider helping us by making a donation.