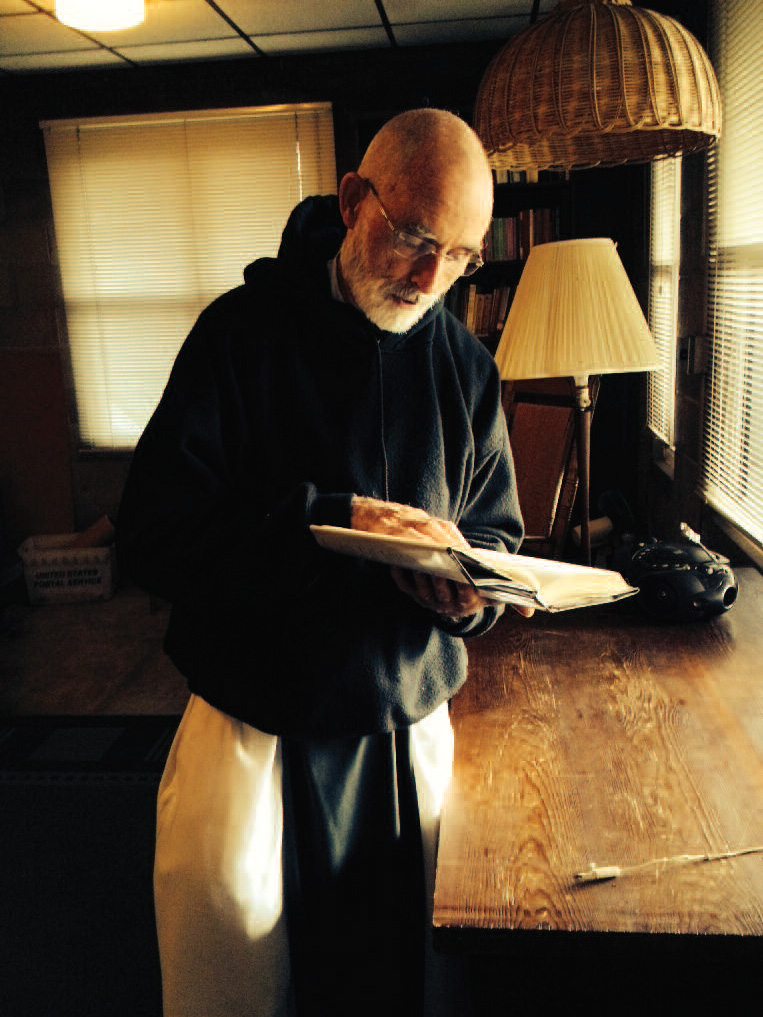

Grace and glory at Thomas Merton’s refuge

Photographs by Bill Murphy

The hermitage in the following passage is at the Abbey of Gethsemani near Bardstown, Kentucky, and was built for Father Louis, also known as Thomas Merton, in the 1960s.

–The Editors

Moonlight awakened me from sleep on the porch of the hermitage. The high moon enhanced the trees with vertical light accentuating lines of the tall trunks. This quiet assembly stood as elegant aristocrats, softly drenched in descending, silvery gauze of courtesy and graciousness.

Nearby, a lone cricket kept careful track of all this while a distant, sustained note spread widely over the fields. This late August coolness has silenced nightly katydids who can rack and vibrate the air from all sides, especially in this close grove, or what is slowly crowding into one. Years ago this yard opened to the sky, with hardy saplings planted to become the sheltering presences they are today.

Settling In

I came here for a week of retreat after a loud morning of heat and bother in the kitchen, of pressure and song at Mass with the community and Sunday crowd. After packing in and setting up, I sat on the chair marked “the Bench of Dreams” and got over my life, with eyes closed, wanting nothing but to be stayed interiorly within what stays you.

Stillness lasted about an hour, and finally my reopened eyes showed the afternoon had gathered to shades of evening. Time moves, and I am moved along. But here there is no urgency to get to the next thing. I pursue no schedule except one of my own devising. I decided to push Vespers back an hour. To be free of a schedule looks attractive, but to have no schedule at all can be as obsessive as having one too rigid. Total freedom leaves me wondering what to do next. I forget that question if I allow the sun to determine my actions.

I would do well to have more of the spirit of the late Br. Harold of fond memory—my peer in the novitiate. He had what might be called “the gift of leisure.” During this hour of my staying, something of Harold’s face moved close and merged with mine. It felt good company, and I don’t know why I thought of him after so many years since his death. I guess I needed it. There was something imperturbable about Harold, and he was a natural for the Buddhism he was long interested in. If there is an aristocracy of souls, he would be toasted in their gentle company.

Harold remained serene even as he gradually slipped into dementia, and I will always remember him sitting contentedly under the cherry tree, with blossoms falling around and upon his head, he not bothering to brush them off. From the hermitage I later heard a saw roaring and soon discovered they had cut down that very tree Harold sat under. It was dying, withered by deep winter freezes. Not far off was a Washington cherry, also slowly dying, planted sideways at a steep angle on a quirk by Br. Donald, who planted both cherries. The slant proved to be stylish.

Walking Prayer

I said the Divine Office at the hermitage while strolling through the grass with my feet bare. Sometime after Lauds I took up with dance or was taken up with it. In that rather isolated sward and wood, the time, space, and privacy allowed for such freedom. Short grass in the big yard remained covered with dew as the sun grew stronger. With feet contacting and feeling ground, I explored the world for what it presented at the moment. Each step, each movement, a bend, a turn, a leap disclosed something delightful to my eyes—colored points of light in the grass, prisms of dew changing hue as I swayed. With legs stretched, back lowered, bending, finding sights at every stride. Blue flowers crouched below grass level, their blue intensified by blue sky; yet lower still, an underlayer of miniature three-leaf green in the thousands, smaller than the clovers you know. The sky is a color too pure to be believed, and trees contrast with bold green against blue. A body must simply stretch to this, must bow to know this realm of honor. My flesh took on the freshness of air and light, and sadness washed out of muscles and bones. I gathered this moment into a poem:

Arriving sun stretched

through pillars of trees

carpets of color

before my feet.Day, in this hidden hall of fame,

is celebrating day,

with my company alone

present to honor being.In honor of being I dance

while robin concurs

with steady, steady chirps—

famous, persistent chirps.

Lectio Divina

Reading during this annual week here is usually long and deep, copious enough to set me on course for the following months. That enables me later to survive better with the shorter spans of reading at the monastery. Hermitage time also allows for serious effort at memorization, and a few years ago I got two or three long poems by Rilke under my belt. It is not enough to get poetry inside your skull. It has physicality and sound that require putting it under your belt, ingesting and getting it inside your body. It takes a lot of work, and I remembered those poems for a year or so. Eventually, left unvisited, unused, they evaporated—gone where? However, if I put my mind to tugging and coaxing one, back it comes, ready to stay awhile for having once been at home in me.

Usually I memorize a poem one line or two at a time. The best hour at the monastery is in the morning, getting ready for Lauds. I read a line, go shave, return to the page, tend to some other detail, return to the page, then repeat the words as I walk to Lauds. Perhaps after the services I revisit the memory. Within a week or so I complete the work, but this is merely the mental part. The next stage is to recite it aloud. That doesn’t come so easily, and harder yet is to recite something in the presence of another person. That almost seems like having to start over again. But once I can recite it to someone else, I have truly mastered the poem. I often used poor Fr. Matthew Kelty as my audience, and with all patience, he bore with hearing me stumble along.

Another essential component in my yearly week of solitude is reading Merton’s private journals. This makes for good company, and eases into a mutual, shared, living solitude—not only because he lived here, but more because his writings sound the depths of what it is to be alone, reflective, and left to the unseen presence of God who does not need to be seen. To sit is enough, to read and watch early autumn leaf-fall swept down from the maples, to feel the fragrant air, to hear faint bells marking time in the distance.

Merton captured such moments and put them on paper. I need to capture them too, but not to commit them to a page. Yet, thanks to reading Merton, I can better see what they are for all their worth.

The Place Is Your Meditation

Meditation, strange to say, seems less a need at the hermitage. Some days I forget it completely since the whole environment seems a meditation. Quiet activity and changing hours easily slide into meditation and ease off again to an awareness of this place itself. The place is alive. A gray lizard crawls with short stops along the sunlit edge of the porch. His serious, angular head bears notions impenetrable, ancestral memories of dinosaur days. My presence represents a novelty to his long, lonely days, and he shows no doubt I am a mere transient. This porch belongs to him. A mud-dauber wasp buzzes in the window where the channel of the frame forms a perfect canal for her mud tunnel. It proved futile to knock that out, since she rebuilt it the next day. Living with such wee creatures invites the mind to enjoy an intimate sense of belonging. You have to set your mind to this intimacy with other wild and living things. You can also get the creeps about it. Wildlife reminds me there are vital differences and distances where I do not belong, as when the red-tailed hawk “schrees,” asserting territory.

Writing either comes spontaneously or not at all. It seems enough to keep a short, daily chronicle, if nothing more, unless a poem comes along begging to be written. A good number of monks and writers who stay here get passionate and find this cottage irresistible for writing and have turned out whole books on the experience—John Howard Griffin; Fr. John Dear; and Fr. Basil Pennington, O.C.S.O.; to name three.

Urge to Dance

I am often inclined while here to express inspiration in dance. Later this week, the sky moved my feet. Looking up, I discovered the half-moon dancing in a circle, forgetting I was stepping and swaying in a circle myself. A jet tracer struck a straight line through tree curves and clouds; cirrus horsetails stretched layer below layer to the horizon. As above, so below do I—toss my white shirt, stretch it as a cloud—lifting and pulling, tossing and dropping, working hands, stretching arms. My body draws down to earth, drifts up to sky, each movement unplanned, a surprising, flowing symphony of what the heart wants to do next, then next, then next. At last the shirt is tossed high, a wannabe cloud, caught and tossed, released to a life of its own in the breeze, the flight, the falling and catching.

I came to the hermitage in need of cutting free again, as I often once did, starting in 1973 when I attended a workshop in symbolism. One of the practices was called “motion to music.” Dancing was not the point, or watching anyone dance. It was to let the motion be what it would be in you. I continued this practice through many years—great for exercise, great for morale. As things developed, I eventually took to it with a twenty-pound weight in each hand.

These days, all too rarely am I caught up in this kind of misbehavior, and usually only at the hermitage. Last year, I really pushed my limits by dancing to a long scherzo by Anton Bruckner. I always carry him in to help my retreat.

Surprise Visitor

Invariably at the hermitage there will be an unexpected surprise, and this year it was the appearance down the road of a tall man who stopped at a distance once he noticed me sitting there. I waved and beckoned him forward. My philosophy is to let the Lord teach me by interruptions. In this case it was not so strange at all—no stranger he was, but the friendly and familiar Bill Chapman, a Quaker I met a year ago. He is review editor of Friends Journal, a leader, teacher, and organizer. He is very concerned that young people are not joining the Society of Friends, and that America has only one hundred thousand Quakers today. He was a friend of Dan Berrigan’s since days he spent as his student at Berkeley decades ago. Bill stopped by, and we exchanged some stories about John Dear, our mutual friend, a strong, vocal opponent of war who is in many ways carrying on the late Fr. Berrigan’s legacy.

Thunderstorm

A retreat is not complete without a good thunderstorm. This broad porch serves as shelter to watch it all develop. Then, the seclusion allows you to go out like a fool and get drenched.

This retreat, no rain came all week long until the last day, late afternoon, and then the downpour was gratifying and robust. Eventually clouds broke and sun came through while rain continued, showering sunlight and rain together. I cartwheeled, became a child again, back in my home yard, knowing only this yard as the whole world, suddenly changed into something wondrous. Rain glistened, backlit by the sun, showing every falling drop for all its worth. Rain appeared to be falling from the sun itself. This rain was meant for this space, felt like something made for only here and now. The narrow yonder of the field where trees attend Our Lady’s statue took on a magical, silver sheen where air misted—a lost wilderness, reverting to some ancient, mythical epoch.

The shower lasted long enough to really cleanse me. The hermitage had been swept and cleaned, and I made ready to depart for Vespers and to return to the monastery totally refreshed.

That evening there happened something of a sign. While laying out bedding as usual on the lumber-shed porch, I saw something I had never seen before, something so unusual I will probably never see it again. The clouds in the east were piled high, lit pink-rose by the setting sun in the west. Suddenly lightning flashed outward in a curious circular array, spreading from a center, coming from no cloud, but from midair in empty space. Soundless, jagged lines stretched out in all directions like a baroque eucharistic monstrance, a wrought-silver sunburst, a complex web of jagged, brilliant netting, briefly seen and gone. All I could do was tell myself that had to be a once-in-a-lifetime apparition. Heaven and earth had kept company with me.♦

This chapter of In Praise of the Useless Life: A Monk’s Memoir by Br. Paul Quenon, O.C.S.O., is reprinted with permission of Ave Maria Press.

From Parabola Volume 43, No. 3, “The Journey Home,” Fall 2018. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.