The Native Peoples of northwestern California (I will be writing mostly about the Yurok Indians) had “money” long before non-native invaders, lusting for gold, brought them nickels, dimes and dollars—and many new ways to die. Before minted United States currency was introduced in the 1850s, the primary monetary medium in the area was dentalia shells -the hard, phallic, tusk-like shells of Dentalium indianorum and D. hexagonum that were traded slowly down from Vancouver Island and Puget Sound. The shells gained in value the farther they traveled, distance and scarcity providing reliable hedges against inflation and devaluation until the introduction of coastwise shipping, after the gold rush.

Five sizes of shells were recognized as money (chi:k) by the Yuroks. The largest and most valuable were two and a half inches long, or eleven to a twenty-seven-and-a-half-inch string. The next, twelve to a string, were worth about one fifth as much, and so on down to the smallest, fifteen to a string. Shells smaller than that were strung as beads in necklaces but were not used by men in exchange (money, we will see, was largely men’s business). The longest and best shells were often decorated with incised lines or with bits of snakeskin and red woodpecker scalp.

Woodpecker scalps themselves were another form of money, called chi:sh. The large scalps of pileated woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus) were the most valuable, but the scalps of the much smaller acorn woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) also had an established exchange value.

All of this money did not comprise a truly “generalized medium of exchange,” as anthropologists define “money,” but was part of a far more complex system of wealth. As far as money itself goes, there was men’s money and, of lesser general import, women’s money, as well as other things, like food, that were themselves forms of wealth. Money from one system was not used to pay for things from another system. Women’s money might buy baskets, for instance, which were made by women, and only the most desperate and déclassé sold food for shells or feathers. Men’s money was quintessentially used to pay for human life: for births, through bridewealth, and for deaths, through blood money. Monetary systems coexisted with less formal systems of barter and gifting. Thus men could at once be extraordinarily single-minded and astute in the pursuit of certain forms of wealth, yet hold greed and stinginess to be the moral failings of no-accounts.

Despite profound differences between their monetary economies, Indian people in northwestern California understood quite readily what “white man money” was when they were introduced to it after contact with whites, at “the end of Indian time.” Minted coins entered the indigenous economy almost immediately, after 1850, and inter-monetary equivalents were soon established. In the 1860s a dentalium shell of the largest size was worth five American dollars and a full string of them about fifty dollars. The next-to-largest shells went for one dollar apiece, the same as a pileated woodpecker scalp (the Karuks called these woodpeckers “dollar birds” well into this century). A wife of good repute (or, really, the children that she would bear) cost about three hundred dollars; more was required to pay for the killing of a man of substance.

Men once kept their accumulated dentalia in elkhorn purses that were secretly compared to a woman’s uterus. They sought to accumulate as much as possible through asceticism and, more directly, through shrewd manipulation of the local legal system, through the marriages of close female kin, and through gambling. When white man money came, the same practices continued, Indians now using it as a medium. So, the people who followed the old ways may seem much like the “primitive capitalists” that earlier anthropologists and psychologists portrayed them to be. But wait. The Yurok mythic creator Great Money, pelin chi:k, both helped to make the world and had the capacity to destroy it. To understand these supposed “primitive capitalists” we must leave off the study of economics per se and take up mythology.

Great Money, a gigantic winged dentalium, is one of the creators of the world. He comes from the North and is the oldest and biggest of five brothers (the five sizes of dentalium money). Together with the next oldest and largest, tego’o, Great Money once traveled and traveled, directing the work of the other creators. His wife is Great Abalone, women’s money from the South.

Great Money is perhaps the most powerful of all the creators. He alone can fly around the entire world, seeing all of it and everything that happens here, and he has the frightening ability to swallow the entire cosmos should he choose to. (Even the smallest Money Brother can do this if offended badly enough.) Great Money has beautiful wings which he is loath to soil, and when he travels by boat he sits in the middle doing nothing, like a very rich man who deigns neither to paddle nor to steer. The other creators did all the actual work in the beginning, under Great Money’s direction. One of them, the trickster Wohpekumew, gave money itself to humankind. He said, “A woman will be worth money. If a man wants to marry her, he will pay with money. And if a man is killed, they will receive money from [the killer] because he who killed … must settle” (A.L. Kroeber, Yurok Myths, 1976). Again, money was brought into the world that Great Money helped to create to pay for births and deaths, for human life, for Life itself.

In the old days, I think, money in northwestern California was a many-layered symbol for what we might call “life-force” or “spirit.” This “spirit” (wewolochek’) was understood as a male contribution to human existence. When one sought legitimate children one paid for their lives with bridewealth, balancing an account with the mother’s natal family which had, in a sense, “lost” her life-force. (Paid-for children “belonged” to the father’s family, and unpaid-for children, “bastards,” had few rights, were viewed as barely alive.) By the same token, one could kill an enemy for one’s own satisfaction if one could pay his family for his life, through blood money, replacing the life one had taken with what was, I am saying, symbolically more of the same. One who could not pay his debts became a slave, had no life of his own. “Everything has a price,” said an old man I knew.

To better understand money-as-life, or as spirit we need to consider the broader category of “wealth,” for there is far more to being “rich,” among these people, than merely having a lot of money.

What the Yuroks and their neighbors have always valued is a balanced variety of wealth, not simply an abundance of money. For example, while in theory a wife might be worth three hundred American dollars, such a simple payment would be without honor. Rather, several strings of dentalia, some good dance regalia, a well-made boat, as well as some gold coins (after whites brought them), with a total value of about three hundred dollars, made a prestigious payment and assured the high standing of the children that followed. The death of a high status man might cost the killer fifteen strings of dentalia, but also valuable regalia and, perhaps, a daughter.

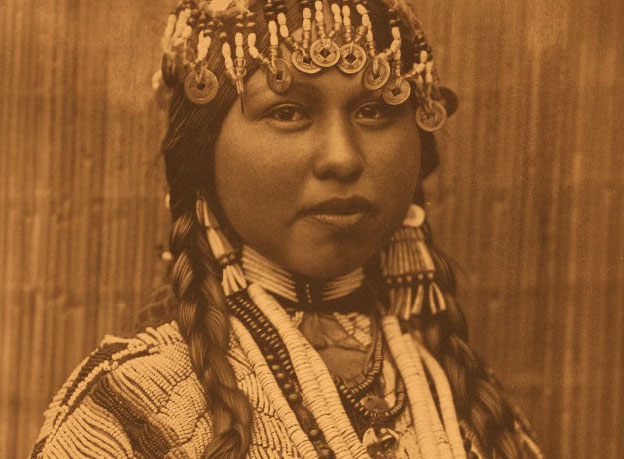

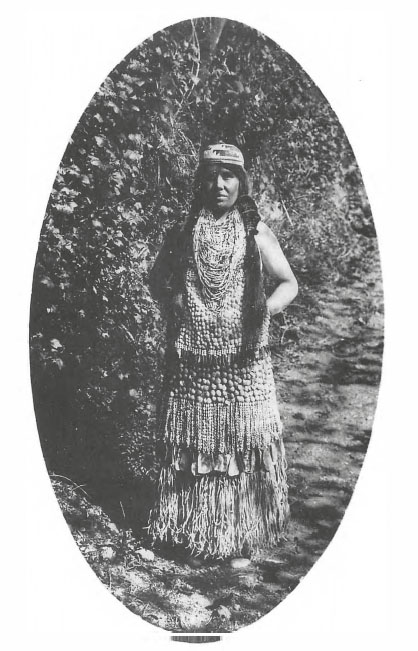

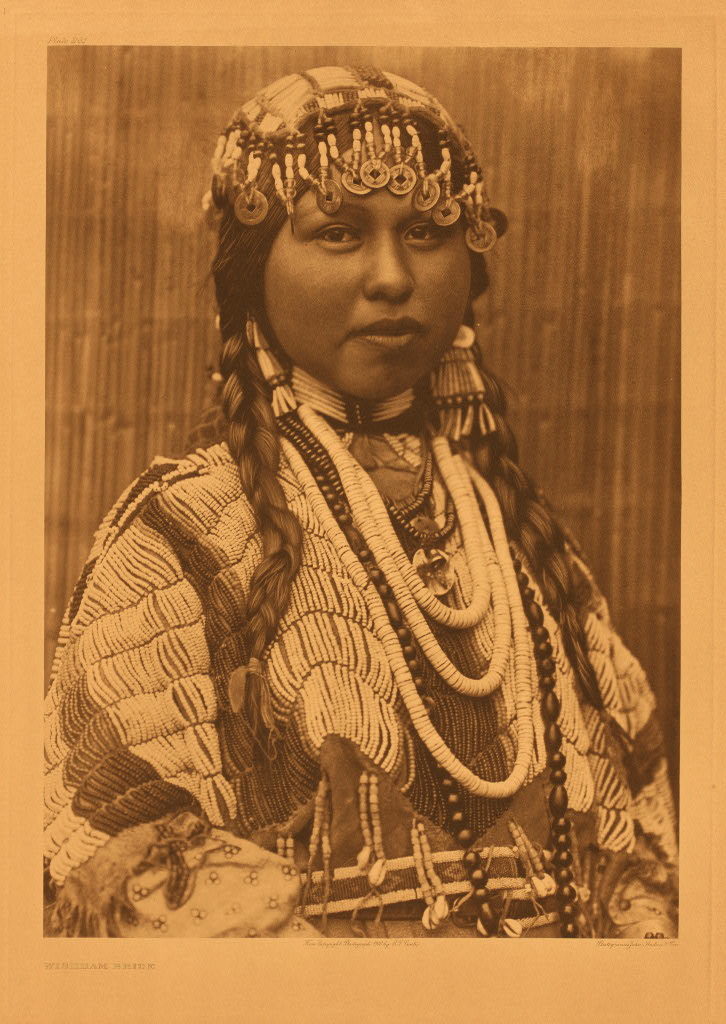

Money, then, dentalia and woodpecker scalps, was once only the beginning of a continuum that included and perhaps culminated in ceremonial dance regalia. These regalia used, today as in the past, in the child-curing Brush Dance and the world-fixing Jump and Deerskin Dances, include dentalia necklaces and headrolls (“headdress” is not a term used by local people, who say “we don’t wear dresses on our heads”) richly decorated with woodpecker scalps. There are fifty-three large woodpecker scalps on a Jump Dance headroll. But these regalia also include beautiful feathers of many other kinds, rare hides and pelts (especially the priceless hides of white deer), large, finely wrought obsidian points, special Jump Dance baskets shaped like purses, with labia, and much else. Women own beautifully made buckskin dance dresses worked with haliotis, olivella, and clam shell, pine nuts and juniper berries, with braided beargrass tassles, worn together with loop after loop of shell necklaces. As the girls and women walk and dance, the dresses sing expressive and unique percussive songs. All of this is wealth, continuous with money: beginning in the nineteenth century people used whole and halved American coins in decorating both men’s and women’s regalia, using the pierced metal pieces in the places where dentalia alone had formerly been used.

Non-locals tend to talk about ostentatious ceremonial “display” of wealth by the Yuroks and their neighbors. But Indians speak of the things themselves dancing: “This headroll danced last year at Hoopa; “These feathers want to dance, so I’m going to let them go to Klamath.” The regalia is alive and feeling. Traditionally, people get money, feathers, and other dance things by “crying” for them-practicing austerities and seeking the compassion of the Immortals, who send wealth to the righteous. And the wealth itself, once in hand, “cries to dance. People say, “Those feathers were crying to dance, so I let them go out to Katimin,” to the Brush Dance there.

Finally, while people cry for wealth, and the wealth cries to dance, the Immortals themselves “cry to see” the beautiful things dance. “Give them what they cry for!” said a Hupa acquaintance at a dance, not long ago. The intricate symmetry of interdependencies bespoken in all of this is delightful and deep.

The Immortals join the human beings, invisibly, to watch the dances, standing in special places reserved for them alone, happy to see the “stuff” dance. The big dances, solemn and powerful, “fix the world,” restore its harmony, ease suffering, fend off disease and hunger, assure more life. Anthropologists have called these dances “world renewal dances.” To read their symbolism in the most direct way, we might say that the dancing of accumulated “life” or “spirit,” emblematized by wealth, affirms existence; it restores the balance of life in the cosmos, reversing the nearly inexorable tendency of the world toward entropy and death by paying off the deficit accumulated through innumerable breaches of sacred law—settling the energy account again, somewhat as deaths are paid for. This is true, too, in the Brush Dances, where the dancing of regalia helps restore a sick child to life. “Give them what they cry for!” Pay back to “The Spiritual” (some people call it) that upon which we depend, so that we may continue to exist. It makes sense, then, that some people assert that the Jump Dance, one of the “world renewal” dances, is also a “fertility dance,” praying for and celebrating, especially, male procreativity. It is through men that the “life” of the cosmos enters the wombs of women, in the local view.

Before the White Invasion, before people converted money into wealth, stringing surplus small dentalia into necklaces, sewing woodpecker (and hummingbird!) scalps onto headrolls, or using such money to pay others to make fine regalia—wealth—for them. After the invasion and well into this century, however, the world seemed beyond fixing to many Indian people. Impoverished by the new economics of scarcity inaugurated by the whites, discouraged by massive losses of population and territory and power, many people converted their ritual wealth back into money, selling off their regalia, cheap, for white man dollars, or pawning it to those with better luck. Regalia left the world, stopped dancing.

Today these transformations continue. With slowly improving fortunes in the region, people are once again converting their money—now federal currency—into dance regalia, commissioning a new generation of skilled creative regalia makers and artists to make new wealth and gaining fame, as in the old days, by letting it dance. Brush, Jump and Deerskin Dances are once more the lively focus of Indian ways, and the esteem in which “dance makers”—those who own a large amount of regalia and have the connections to borrow even more—are held is high indeed. Now, as probably always, money and wealth alike mean many things to different people, and those many meanings continue changing through time, in history, where these and all people are located. But I have risked a generalization.

Dentalium shells, men’s money (compared sometimes to the male member), woodpecker scalps of the brightest scarlet, unmistakably like the blood of life itself, include among their many meanings mortal life-force, the energy of reproduction and continuation. From an Indian point of view, l believe, this “money,” not love, makes the world go ‘round.

There is a great, cosmic account that must be kept in balance if the people are to continue to survive. (The Karuk artist Brian Tripp entitled a recent work “The Best Things in Life Aren’t Free.”) In bridewealth, death settlements, and dancing, money and other forms of wealth are paid back into that great account. “Everything has a price” does not mean that everything is for sale, but that there is a necessary energic balance that must be maintained, because it is what makes mortal life possible and allows it to run through the generations.

The Indian peoples of northwestern California—Yuroks, Hupas, Karuks, Tolowas, and others—have tended to use money and wealth alike as master symbols of that which creates and enlivens the great diversity of meaningful forms in the world. Theirs has been, if you will, a spiritual economy. Non-Indian Americans, I think, have generally and ever-increasingly tended to reduce the many meanings and values of life-forms to the arbitrary monetary exchange values of those forms, putting virtually everything up for sale: a radically material economy. There is an enormous difference. ♦

From Parabola Volume 16, No. 1, “Money,” Spring 1991. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.