I met Jonathan F.P. Rose in Manhattan, the week a snow storm knocked out power in much of the Northeast. Heating by woodstove and carrying water home from the local fire station for five long, cold days left me feeling a bit rough and smoky, not to mention unprepared, to be sitting in the comfortable offices of his company in a historic old building near Grand Central Station. Yet the moment I met Rose, a tall, friendly man who met me talking and moving at a confident stride, I realized that my days as a kind of suburban pioneer woman, muddling along in a harsh new world that everyone blamed on global warming and our decaying infrastructure, was the best possible situation to meet a new kind of green pioneer.

The Roses are one of the oldest and most successful real-estate families in New York, well known for their dedication to civic life and for giving back to the place where they gained so much. There is the Rose Center for Earth and Space at the Natural History Museum, the Rose Main Reading Room at the New York Public Library, among other places, and many Roses have served on boards from the Philharmonic to the Botanical Garden. Jonathan Rose is building on that legacy in a new way. In 1989, he founded the Jonathan Rose Companies, a real-estate development, planning, consulting, and investment firm focused on creating places to live and work that are better adapted to our changing world.

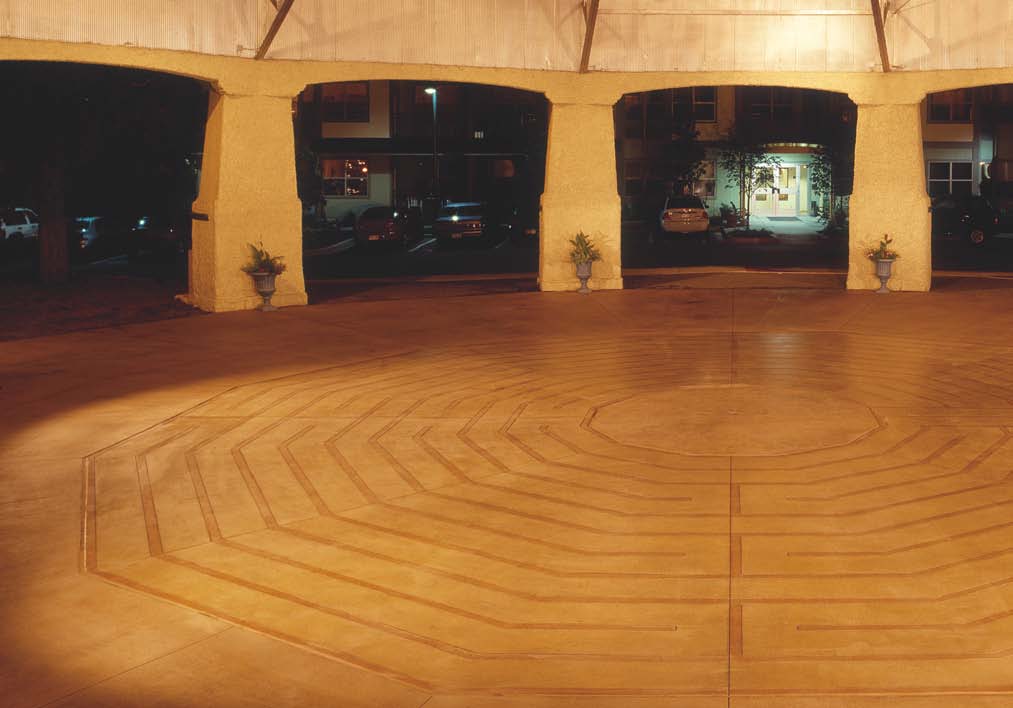

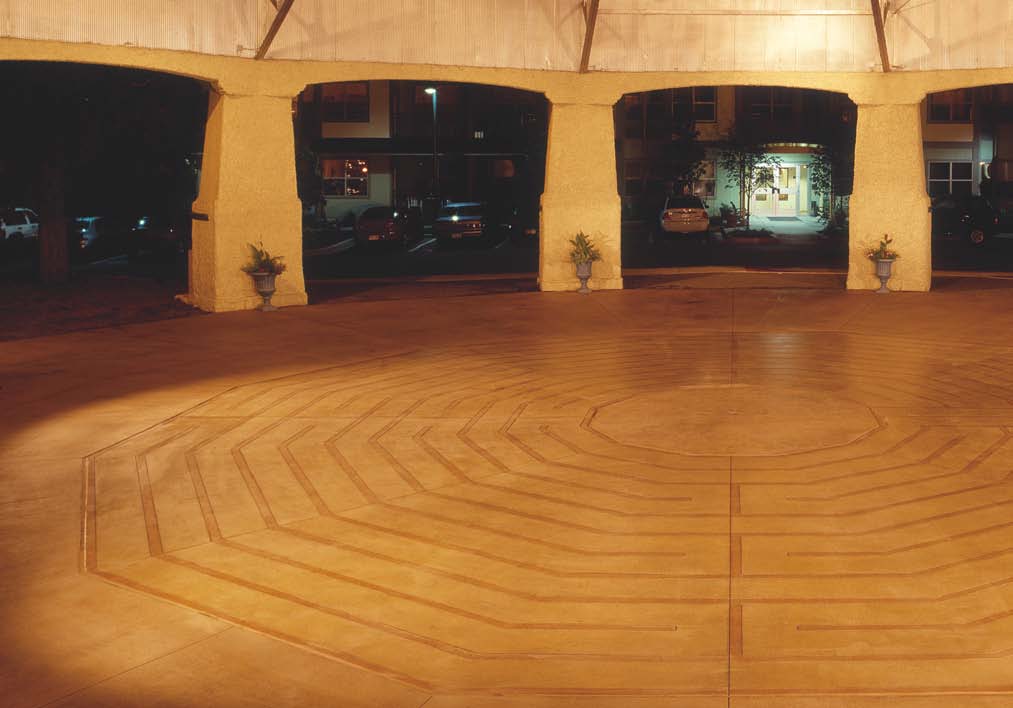

As we settled in to talk, Rose spoke about growing up in an atmosphere where making the world a better place was the conversation at the dinner table. “I do remember as a teenager going through a kind of existential crisis once,” he told me. “I literally went to my parents and asked them what the meaning of life was. My mother said ‘the meaning of life is to be generous and to give to others.’” Rose deepened this understanding with the help of his Buddhist teacher Gelek Rinpoche, his Jewish teacher Rabbi Zalman M. Schachter-Shalomi, and the many other spiritual teachers who visit the Garrison Institute, the contemplative retreat center he co-founded with his wife, Diana. Through his work Rose is building not just green housing but new kinds of civic, cultural, educational, and open spaces. At the center in Garrison, New York, he and his wife, Diana, are helping people from all traditions to find new ways of being conscious together in an inner and outer sense—better able to take practical action to repair the torn fabric of the world.

—Tracy Cochran

Jonathan Rose: The military has a phrase called “VUCA” and it stands for volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. It describes the nature of the world that we are facing. The old systems, thinking, and political debate often do not recognize this. We see enormous volatility in extreme weather events and climate change and in extreme economic events. And we’re going to see much, much more volatility.

We have grown as a culture and as a system to understand how to deal with complicated systems. An example of complicated system is the New York City sewer system. It’s very complicated, but it’s very predictable. It has results that can be calculated. In a complex system the pieces are all interdependent rather than linear. Causes and conditions intertwine, and what goes in and what comes out are often unpredictable or unknowable. They can be intuited, but things are not entirely clear. There is much more ambiguity. In a linear system, even a complicated linear system, you can have definable results while in a complex system you have ambiguous results. We are in that realm of complexity now, which makes it harder to have certainty about what to do.

Volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity: that defines the world we are in. It requires different kinds of solutions, different kinds of governance, and it requires a different kind of state of mind. The very rational linear state of mind that created the industrial revolution and brought enormous prosperity and material good to the world also brought many of the problems that we have now. By failing to look at whole systems, that world view didn’t take into account what economists call externalities. You could have a factory that was profitable while it was polluting the water and the air—dumping its wastes into “the other.” Those externalities had no cost so they weren’t taken into the costs of the accounting, but they actually had a huge societal cost, a cost to the commons. But if nature is to be the sink and the absorber of our waste, that can only be done when the population is small—my guess is up to a billion people or so. Soon, perhaps even the day of this interview, the population of the earth will have crossed to seven billion people. By 2050, we will be closer to ten billion people. Nature has no margin at this scale. Add to this population the increased prosperity of humans on earth and we completely exceed the carrying capacity of nature.

Everything that was external and away from us surrounds us now. The economy is globalized. But climate change knows no boundary except the earth itself. The effects will reach every one of us.

Parabola: How are we to change?

JR: The first thing we have to change is the way we see things, moving from a linear view to a holistic view. It is hard to understand one’s effect on the whole system. To reduce environmental impacts, many more people are paying more attention to turning off lights when they leave a room, for example. This is a very good thing but many Americans are far more polluting in their auto use and other transportation habits. One of the healthiest things we can do for ourselves and for the world is to walk. Yet we don’t live in a world that is organized for walking. Many Americans live in suburban areas that are designed to require auto use and make walking very impractical for most activities, so there is an inherent pattern in the land use system that deeply shapes our environmental behaviors.

If we want to shift our environmental behaviors, we will not get there by proposing changes that lead to increased suffering. Environmental solutions will be mostly accepted if they lead to increased pleasure and increased quality of life. What we are seeing is that when cities and communities create bike lanes and great safe sidewalks planted with trees, when the train stations have winterized parking for bikes, when the system is designed to encourage people to have healthy behaviors, they eagerly do it. Somebody told me today that the biggest problem with the bike lanes in New York is that they are crowded, and that’s because they were made safe and convenient.

vated former Capuchin monastery that is situated

on a 12 acre site overlooking the Hudson River,

connecting contemplative wisdom with social

and environmental action.

P: Consciousness seems to change when it has to. In northern Westchester where I live, during this power outage the Salvation Army has set up a warming center in the local middle school. It was like the village green. People of all ages and income levels were mingling there to get warm, to charge our phones and computers, and to talk about how the weather is changing and what we can do about it. This willingness to change and to pull together just seemed to appear. Of course it may be very temporary.

JR: From an evolutionary point, human beings have the patterns of a “we map” and a “me map.” These are cultural but also cognitive and neurological patterns. The “me map” is the self-preservation model, single issue, single response, very linear. If a bear jumps out of the woods, you fight or flee. The “me” issues, the ego issues, are all either based on fear or desire based issues. We have a world that has increasingly been designed around stimulating that. Advertising tries to get you to want something and since 9/11, the language of politics has been based on fear and encouraging consumption. It’s very difficult to deal with complex issues from this “me” way of thinking. But we are also highly evolved for altruism. We survived much more in groups than as individuals, and you need a different set of skills to live in a group. You need to collaborate, to concede, to compromise, and to lead, and you need to balance those all the time. Altruism is a positive evolutionary trait. It comes with a neurological system—mirror neurons. It comes with a cultural system—every culture has a system of collective decision-making and a way of appreciating the common good. This system is very good at dealing with complexity.

We learn that the way we frame messages can stimulate an altruistic mind or an egocentric mind. Just by reading the word “money” right now shifts you more into the “me” part of the mind. We know that we can also trigger pro social behavior through the messages and commitments of our society. As individuals, we can put our fingers on the scale of the collective good—which is really not the opposite of the individual good because everything we use or rely upon comes from so many sources that the collective good is our individual good.

P: Does the emphasis of spiritual practice have to change now to keep the global picture and our impact in mind?

JR: Every spiritual tradition has a lineage of generosity. But what we really have to do is to shift our behavior. At Garrison Institute, we have a program called Climate, Mind, and Behavior, in which we look at how we behave and how we shift. One of the things we’ve learned is that attitude follows behavior rather than behavior follows attitude. We educated, intellectual Westerners tend to think that we need to convince people, but the mind is much more embodied than we think. There is a deep mind/body communication. If people walk more, there is a view that shifts with it.

P: I found I’ve been conserving water since we lost power.

JR: The key is persistence. We know that people can be very flexible and adapt very quickly. The issue is how to make those adaptations persist. It’s very clear that one of the keys to that is in collective behavior and the collective message that we can live comfortably and consume just a little less.

P: We have to shift our notion of what it means to live a good life.

JR: Yes, and more. There was an American aspiration highly manipulated to desire a single family home in the suburbs. By highly manipulated I mean there was actually a very strong debate at the end of World W II as to whether the new housing programs should fund multi- family urban housing or single-family suburban housing. Urban housing became defined in Congress and the political realm as socialistic, and the single-family house was defined as the ideal capitalistic investment. Joseph McCarthy was funded by the national homebuilders association in the 40’s, to go around the country and denounce multifamily housing in the cities and promote single family housing. There were many forces that set this aspiration; it wasn’t entirely political. People also wanted more space and they wanted to be close to nature.

Yet now there is a very big paradigm shift, a movement back to the cities. It’s called “the bright flight,” in which the most educated young and old people in America are less frequently aspiring to a suburban house but to an urban apartment, and there are significant challenges and opportunities that come along with this. Simply by living in New York City you use one quarter of the energy you use living in the suburbs.

P: Do you regard yourself as having a Buddhist practice? Or a Jewish practice?

JR: I have a Buddhist practice and a Jewish practice. I draw from both traditions and both have deeply influenced my thinking. In 1989, I started a real-estate development company whose mission is to repair the fabric of communities. That came directly from the Jewish phrase tikkun olam, which means to repair the fabric of the world. This is the Jewish view of the mission of humans on earth, since the world was doing fine until we got here. We have to repair the world that we destroyed. But I also take very seriously the Buddhist intention to relieve suffering. I’ve said several times that we have to change our state of mind, from a self-centered state of mind to a more communal state of mind, from “I” to “we.” I really believe that Buddhism offers a clear path towards helping people see how to do that. It’s a very good social and mental technology for that transformation.

The mission of this company really is to show that one can use a for-profit system to achieve environmental and social goods, and we’re doing it. I’m sitting here smiling as I say this because a couple of hours ago I visited the completion of a project in Harlem, very green healthy housing for low-income seniors. It has beautiful gardens and a back yard and social support services. I really believe the world is a better place for the creation of that building, and that the lives of everyone involved in the project have been enriched by being involved in something that makes the world a better place. And our firm undertook it as a for-profit business, in partnership with a local community based not-for-profit group, HCCI, Harlem Congregations for Community Inc.

P: How do you see the sacred and the secular?

JR: I don’t think there is a line between sacred and profane. I think we are interdependent. This is a fact, just like gravity, this is the nature of the world. But we can either see more of our interdependence or not. HCCI, the not-for-profit we just completed the senior housing with, is a consortium of about one-hundred congregations in Harlem which have come together to rebuild their community—primarily Christian but a few synagogues and a few mosques. It wasn’t a question of sacred and profane for them but of the need to come together for the common good.

I have an image that is coming to mind for what we are trying to do: combing the hair of complexity—taking the knots and smoothing them out and finding a solution that’s a win for everybody, that makes the community a little more coherent and a little more in alignment.

P: In alignment with the deeper truth of interdependence and the call to repair the world?

JR: Yes, and by the way, all the while you do that there is more and more chaos being created elsewhere in the world. There is an ongoing process of coherence and chaos. I just feel that the more of us who have our thumb on the side of the scale of coherence and community and compassion, the better.

P: There is much talk about “enoughness” these days. How can we help people learn that enough is enough?

JR: Part of it may have to do with social signaling. For example, studies show that in Scandinavia people seem to be much more content with what they draw from the public realm—from the beauty of the environment and the common social good—as opposed to their private prosperity. But in fact, many studies show that increased prosperity—once you get people above a certain level of poverty—does not increase happiness. What does seem to increase happiness are collective activities, family and community, being together rather than alone. Also generosity. There is a lot of science that shows that the more people are altruistic or contribute to society, the happier they are. Enoughness is about not looking to material goods and success for satisfaction, but not limiting the pleasures of community and of generosity. This is not an impoverished life. The movement leads to a richer, happier life.

P: I noticed during the power outage that I’ve even lost track of what darkness is and what solitude can be like in the darkness.

JR: I also believe in what St. John of the Cross called the dark night of the soul and sometimes we have to immerse ourselves in despair to be even more motivated to do good. Sometimes when we design a program at the Garrison Institute we’ll end an evening with something very unsettling, so that people sleep on it and wake up the next morning more motivated to resolve that uncertainty.

P: That’s really interesting. Sometimes I despair that spiritual retreats in this country are almost indistinguishable from spa treatments. It’s a way to be more comfortable, not to face uncertainty.

JR: Spiritual practices that reduce stress are useful but incomplete. We believe that the goal of spiritual practice is to understand the nature of reality—interdependence—and use it to help make the world a better place. When one is jammed in one way or another, one is pushed much more in a “me” space. When you feel more space, more integration, you are much more likely to act on behalf of the whole. The nature of the way one acts in the world is influenced by the way we see and experience the world.

P: What’s arising?

JR: My goal for our company is to increase the scale in which we’re working. We’ve been hired by the city of Sao Paulo in Brazil to develop a plan for how to generate a million units of affordable housing over the next twenty years, and we had to come up with a whole structure and system for how to do it. I’m interested in working much more globally. The rate of urbanization is extraordinary, bringing problems but also amazing opportunities. So I want to work on a greater policy scale and also have a bigger impact.

P: What would you say to the readers of Parabola?

JR: In the 1980’s I joined a group called the Social Venture Network, an amazing group of people, including the creators of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream, and the founders of the Body Shop and Whole Foods. I remember thinking that if only I was in the retail business like they were, then I could really make change. But I realized that you start from where you are, and that I could create a transformational real estate company.

Have high aspirations, yet carry it out in a language and other practical ways that can help the world. We need to connect the knowledge with the action. There are a lot of places where people get together and talk and this is a good thing—it builds community. But I believe that because of the state of the world today, we also need to commit ourselves to transformational action. ♦

From Parabola Volume 37, No. 1, “Burning World,” Spring 2012. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.