THE ILLUSION OF SEPARATION

At night on my bed I longed for my only love.

I sought him, but did not find him.

I must rise and go about the city,

the narrow streets and squares, till I find my only love.

I sought him everywhere but I could not find him.

—SONG OF SONGS 3:1–2

O Lord, you Supreme Trickster! What subtle artfulness you

use to do your work in this slave of yours. You hide yourself

from me and afflict me with your love. You deliver such a

delicious death that my soul would never dream of trying to

avoid it.

—Teresa of Avila, THE BOOK OF MY LIFE

I’ve had enough of sleepless nights,

Of my unspoken grief, of my tired wisdom.

Come my treasure, my breath of life,

Come and dress my wounds and be my cure.

—Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi, “I’ve Had Enough”

THE FIRE OF SEPARATION

There is a longing that burns at the root of spiritual practice. This is the fire that fuels your journey. The romantic suffering you pretend to have grown out of, that remains coiled like a serpent beneath the veneer of maturity. You have studied the sacred texts. You know that separation from your divine source is an illusion. You subscribe to the philosophy that there is nowhere to go and nothing to attain, because you are already there and you already possess it.

But what about this yearning? What about the way a poem by Rilke or Rumi breaks open your heart and triggers a sorrow that could consume you if you gave in to it? You’re pretty sure this is not a matter of mere psychology. It has little to do with unresolved issues of childhood abandonment, or codependent tendencies to falsely place the source of your wholeness outside yourself. The longing is your recognition of the deepest truth that God is love and that this is all you want. Every lesser desire melts when it comes near that flame.

You realize that not everyone experiences this. For some people, the spiritual journey is not so dramatic. It’s less about the overwhelming desire for union with some invisible Beloved than it is about quietly waking up. It’s about developing compassion, rather than suffering passion. There are people who never doubt that God is with them, and so there is nothing to long for.

But there are those, like you, who have felt the Divine move like an ocean inside them, and, incapable of sustaining an unbroken relationship with that vastness, feel they have been banished to the desert when the wave recedes. There is a tribe of holy lovers, who have tasted the glorious sweetness that lies on the other side of yearning, when the boundaries of the separate self momentarily melt into the One, before the cold wind of ordinary consciousness blows through again, and restores your individuality. You would risk everything to rekindle that annihilating fire. You would leave your shoes at the door and run after the cosmic flute player, if only you could hear that music one more time.

You give up everything for one glimpse of the Beloved’s face. You sneak into his chamber in the middle of the night and say, “Here I am. Ravish me.” But when you awake the next morning, swooning and alone, you realize you missed the entire encounter. You throw your clay cup on the cobblestones and it shatters. You thought you would marry, bear babies, make a career in broadcasting. You wander city streets during siesta hour and wonder where he is sleeping. Your longing and your satisfaction are reciprocal. The moan of separation is the cry of union. . . .

This Beautiful Wound

Sometimes an arrow of love pierces the heart and penetrates the deepest core of the soul so that she doesn’t know what has happened or what she wants, except that all she wants is God. She feels like the arrow has been dipped in a poisonous herb that makes her reject herself for love of him. She would gladly give up her life for him. It’s impossible to explain the way God wounds the soul or to exaggerate the agony it causes. It makes the soul forget herself entirely. Yet this pain carries such exquisite pleasure that no other pleasure in life can compare to that happiness. The soul longs to die of this beautiful wound!

—Teresa of Avila, THE BOOK OF MY LIFE

Death has been my own gateway to the numinous. I did not pick this path. I have simply experienced an unusual number of tragic losses, which propelled me to plunge into spiritual practice as if my life depended on it, which in many ways it did. As the years went by, death after death continued to reveal traces of grace. As long as I can remember, my sorrow has been the catalyst for my longing for God.

Yet the inner harvest these multiple losses yielded did not prepare me for the avalanche that would sweep through my life, annihilating everything in its path. The year I turned forty, the day my first book came out, a translation of DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL by the sixteenth-century Spanish saint John of the Cross, my fourteen-year-old daughter, Jenny, was killed in a car crash.

Suddenly, the sacred fire I had been chasing all my life engulfed me. I was plunged into the abyss, instantaneously dropped into the vast stillness and pulsing silence at which all my favorite mystics hint. So shattered I could not see my own hand in front of my face, I was suspended in the invisible arms of a Love I had only dreamed of. Immolated, I found myself resting in fire. Drowning, I surrendered, and discovered I could breathe under water.

So this was the state of profound suchness I had been searching for during all those years of contemplative practice. This was the holy longing the saints had been talking about in poems that had broken my heart again and again. This was the sacred emptiness that put that small smile on the faces of the great sages. And I hated it. I didn’t want vastness of being. I wanted my baby back.

But I discovered that there was nowhere to hide when radical sorrow unraveled the fabric of my life. I could rage against the terrible unknown—and I did, for I am human and have this vulnerable body, passionate heart, and complicated mind—or I could turn toward the cup, bow to the Cupbearer, and say, “Yes.”

I didn’t do it right away, nor was I able to sustain it when I did manage a breath of surrender. But gradually I learned to soften into the pain and yield to my suffering. In the process, compassion for all suffering beings began unexpectedly to swell in my heart. I became acutely aware of my connectedness to mothers everywhere who had lost children, who were, at this very moment, hearing the impossible news that their child had died. I felt especially connected to mothers in war zones, although I lived in safety and abundance in America.

Interdependence with all beings has never again been an abstract concept to me. I am viscerally aware of my debt to every blade of grass. Innumerable, unexpected blessings emerged from the ashes of my loss: a childlike wonderment and gratitude in the face of the simplest things: a bowl of buttered noodles, reading poetry to my husband in bed, two horses prancing across the field behind our house. These are the blossoms that unfold from my growing relationship with the Mystery of Love. This is the holy potion that has been given as the antidote to my brokenness.

Grief strips us. According to the mystics, this is good news. Because it is only when we are naked that we can have union with the Beloved. We can cultivate spiritual disciplines designed to dismantle our identity so that we have hope of merging with the Divine. Or someone we love very much may die, and we find ourselves catapulted into the emptiness we had been striving for. Even as we cry out in the anguish of loss, the boundless love of the Holy One comes pouring into the shattered container of our hearts. This replenishing of our emptiness is a mystery, it is grace, and it is built into the human condition.

Few among us would ever opt for the narrow gate of grief, even if it were guaranteed to lead us to God. But if our most profound losses—the death of a loved one, the ending of a marriage or a career, catastrophic disease or alienation from community—bring us to our knees before that threshold, we might as well enter. The Beloved might be waiting in the next room.

THE IMMOVABLE SPOT

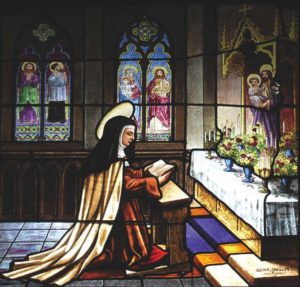

The Great Sixteenth-Century Spanish mystic Teresa of Avila was not always in love with God. In fact, during her first twenty years in the convent, she alternately envied and disdained the girls who openly wept with the pain of separation from their Beloved. Teresa prided herself on being a practical person. “God dwells among the pots and pans,” she declared. If one of the young nuns in her care displayed a tendency toward altered states of consciousness, Mother Teresa would yank her from the chapel, stick a broom in her hand, and order her to sweep the portico until the delusion passed.

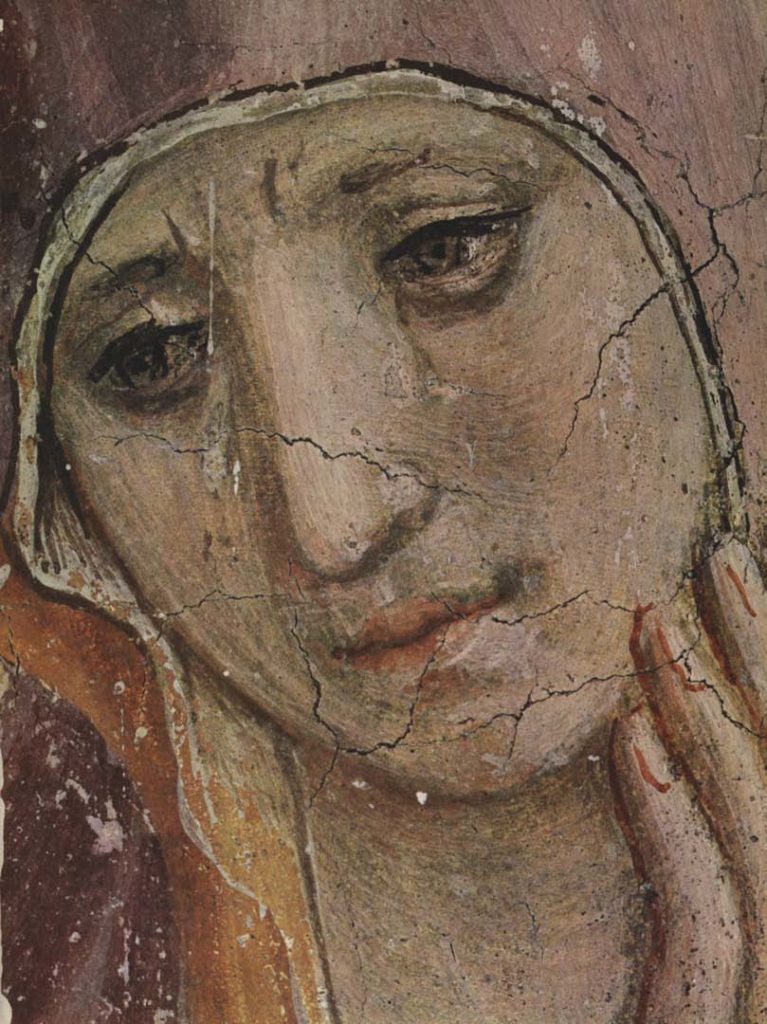

One day, however, during her thirty-ninth year, the Holy One rushed the boundary Teresa had built around her heart. The efficient nun was bustling through the halls of the convent, readying the place for an upcoming festival, when she noticed a statue of Christ at the pillar unceremoniously propped against a wall. Irritated, Teresa bent to pick it up. Suddenly, her eye caught his, and she was transfixed.

Christ’s face radiated unbearable suffering and unconditional love. Even as his back was bent and scored with lacerations, the blood dripping into his eyes from the thorns that pierced his scalp, he gazed at Teresa with a tenderness that felt absolutely personal and offered her his undivided attention. Never had she felt so fully seen. Never had she imagined herself worthy of such a love as he was pouring upon her.

Teresa’s knees buckled and she slid to the floor at his carved feet. Then she kept going. She unfolded her body in full prostration, pressing her face to the ground, arms stretched above her. Her heart overflowed and she began to cry. She cried tears of longing and tears of fulfillment. She wept with remorse for never having loved Christ as he deserved to be loved, and she wept with supplication that he never, ever leave her.

Like the Buddha as he sat in meditation under the Bodhi Tree, vowing not to move from that spot until he had broken through to enlightenment, Teresa drove a bargain with her Lord. She told him that she would not get up until he gave her what she wanted: the strength to adore him and never to forsake him again. Once the dam had broken, all the tears of a lifetime cascaded through her heart, and Teresa lay weeping for a long time. When she was spent, she rose transfigured. From that moment on, Teresa of Avila began to undergo the stream of visions, voices, and raptures for which she is so famous.

Near the end of her life, Teresa finally experienced the union of love she had so fervently longed for—in what she referred to as “the seventh chamber of the interior castle,” where the Beloved dwells at the center of the soul. Once this love had been consummated, all the supernatural phenomena fell away, the ecstatic states and levitations ceased, and Teresa became a fully integrated being. Like the bodhisattva in the Buddhist tradition, Teresa found the highest expression of spiritual love in dedicating herself to the service of others. ♦

Reprinted by permission from Mirabai Starr, GOD OF LOVE (St. Paul: Monkfish Book Publishing Company, April 2012). From Parabola Volume 38, No. 3, “Power,” Fall 2013. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.