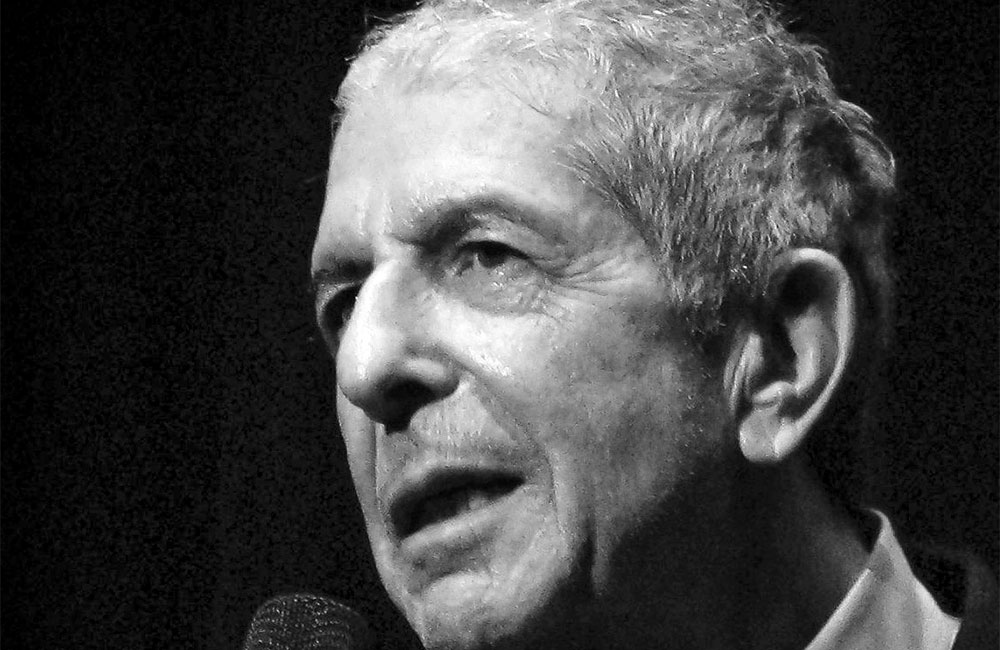

King David, Leonard Cohen and the Search for Meaning

Since Leonard Cohen died, I’ve been thinking a lot about King David, perhaps the ur-ancestor in Cohen’s lineage as a Jewish poet who also sought the “secret chord” that would bring God joy.

King David did everything large-screen format. He was a warrior without peer, a prodigious lover, the unifying king of ancient Israel, the seed of messianic consciousness (it is said the Messiah will come from David’s line). And he was also a man who experienced immense grief and suffering in his short time on earth. He was a betrayer, an adulterer, and a murderer; he was a grieving father and a confused monarch. Robert Pinsky writes that “even though [David] is both horrible and beautiful, he is so in a way that reminds you of human beings.”1 Indeed, there is something about David that brings us closer to our own imperfect selves – how vast our longing to love, how devastating our failures to do so. In this spirit, it is worth remembering that before he was king, before the fame and the infamy, David was a shepherd and a poet. And in a way, it is those two grappling archetypes inside him that makes his story so uneven and so compelling.

The Shepherd

In fact, the first thing we learn about David is that he is a shepherd. When the prophet Samuel, with the intention of identifying the future king, asks Jesse the Bethlehemite to bring forward his sons, the prophet sees a row of hearty young men, but he knows the king is not among them. “So he asked Jesse, ‘Are these all the sons you have?’ ‘There is still the youngest,’ Jesse answered. ‘He is tending the sheep.’2 David is sent for, recognized, and secretly anointed.

It is easy to either romanticize the shepherd’s calling (the humble/simple servant of God), or ignore it altogether, overly-metaphorized as it has been (the shepherd as religious leader and the people as the flock). But we can’t ignore it – almost all of the patriarchs and matriarchs in the Hebrew Bible were shepherds, a job that most fundamentally requires practice in the art of caretaking. As a precocious wunderkind, David tells Saul that he is ready to fight the giant Goliath precisely because he has killed bears and lions as part of protecting his sheep. The shepherd bears this heavy responsibility to assume responsibility for others, but it is borne of an awesome knowing that each of us are caretakers for the other.

It is not that David always succeeds as a shepherd in the conventional sense; that is, in literally protecting his family and his people. In truth, his failures to do so are profound and chilling. But David is aware of this responsibility, chosen for this responsibility, and his struggle with how to live into this responsibility is a struggle that is familiar and intimate to each of us. How can we realize our obligation to serve and love others? Emmanuel Levinas says that in our choosing to come into awareness of this responsibility, we become chosen.

The Poet

The rabbinic tradition imagines David going to sleep each evening with his harp by the open window. When the night wind blew through, he would awake and compose psalms. Before he knows for sure that David is a threat to his throne, King Saul brings David into his house to calm his vexations by playing soothing music.3 The Books of Samuel tell us that David was a man who was loved by many, but David himself only seems to express love for God, for the Beloved without horizon. We see this in David’s ecstatic dancing before the Ark of the Lord, as it is brought to Jerusalem, with whirling and joy unbridled enough that his wife upbraids him later for not acting like a king. And we see this love of God in his greatest gift to those who come after him – in the Book of Psalms.

Traditional Jewish teaching imagines David to be the author of the Psalms, and in this imagining, David becomes the master of the entire spectrum of the emotional register. We have his outer story in the two books of Samuel (and to a more limited extent, in Chronicles), and we have his inner story in the Psalms – something we don’t have access to with any other biblical figure. Through the 150 psalms, we can read David expressing grief and remorse, anxiety and fear, longing for union and revenge, pleas for rescue, and ecstatic love. And in the presence of these psalms, we can feel our own versions of these emotions vibrating with his.

Praise

In a composite sense, through the psalms, we slowly get at what we imperfectly call, praise. David knows that praise does not consist of saccharine one-dimensional platitudes designed to flatter the Divine, as we often understand it to be. Praise is a cry of life. It is not always to be offered in relation to getting what we want. It is confessional, not limited to the contemporary usage of getting something specific off our chests, but in the ancient sense of speaking what is true. Praise has something to do with allowing ourselves to be scarily alive in our innate messiness; allowing ourselves to sing to the hollow and hallowed darkness.

Leon Wieseltier, a dear friend of Cohen’s, wrote something4 that stood out for me in the host of wonderful obituaries that appeared after Cohen’s recent death. He describes Cohen’s response when Wieseltier’s fifth-grade son (for a project he was doing at school) asked him: “Dear Uncle Leonard, did anything inspire you to create ‘Hallelujah’?”

Cohen wrote back – “I wanted to stand with those who clearly see G-d’s holy broken world for what it is, and still find the courage or the heart to praise it.”

Emily Dickinson wrote that “pain is missed in praise.” David does not miss it. He gets that praise is a full-body endeavor, a commitment to showing up day after day in our beauty and in our ruin. The Benedictine nun and writer, Kathleen Norris, writes gorgeously about the psalms – which she describes as “wild and often contradictory poetry” – in her book, The Cloister Walk. “The psalms demand engagement, they ask you to read them with your whole self…[they] reveal our most difficult conflicts and our deep desire to run from the shadow. In them, the shadow speaks to us directly.”5

As we often say in synagogue, trust that if a psalm does not speak to you at any given moment, that it is speaking to another in our midst. The psalms more than anything else in the liturgy ask us to pray with this awareness that we are opening our mouths collectively. And I think it is precisely the psalms’ insistence on our shared experience that connects our poet-selves to our shepherd-selves. The poet prays, and when the poet is able to break out of the self-absorption (that too often characterizes the search for meaning), and move through her own pain towards a sensitivity to others’ pain, she touches the shepherd’s cloak.

Embedded in the Grammar

A teacher of mine in Jerusalem taught that there is a moral dimension in the bracha (blessing) formula in Judaism, where we say, “Blessed are You, the Lord our God…” Our God. We say this and if we are really listening, we realize that something so personal and intimate – prayer – is actually bringing us further in towards community, seen and unseen, Jewish and non-Jewish. We are not only praying on our own behalf. Somehow embedded in the grammar is a glimpse of the collective source and the collective voice singing to this source. The awareness in the bracha becomes imperative.

And it strikes me now, years after receiving this teaching, that there is a reason “Our God” comes in the second clause of the sentence, following after, “Blessed are You.” Before we learn to say our when we pray, first we need to learn to say You. Just the very act of saying You (capitalized or not!) draws us out of the muteness of our inchoate suffering and joy by bringing us into the possibility of relationship. David as poet teaches us how to say You; he holds nothing back and pours out his heart no matter how broken, sacrilegious, or shuttered. David the shepherd teaches us that it is only after we’ve done this that we can say our. And so it is within the blessing itself that the poet and shepherd connect. Imbedded in the grammar.

Just Keep Going

In The Book of Hours, Rilke describes God forming us and then softly giving us words we are doomed to forget as we walk out of the tunnel into life:

You, sent out beyond your recall,

go to the limits of your longing.

Embody me.Flare up like a flame

and make big shadows I can move in.Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.Don’t let yourself lose me.

To me, this line – “Just keep going” – is the point of the Psalms, and really the entire search for meaning. During an early initiatory experience, the spiritual teacher Adyashanti says he heard an inner voice propelling him forward – “Keep going, keep going.”6 We could interpret this any number of ways, but I like tying it back to Rilke and the Psalms – no feeling is final. It is not just for our own psychology and our placing our trust in the dynamic nature of things, knowing that this phase/emotion/constricted moment, too, will pass. It is not just a reminder to have courage and to continue along no matter what comes. “Keep going” is also a theological mandate on the path of searching for meaning. We are still in the process of becoming, as God is still in the process of becoming. There is no arrival. In their own distinct ways, our poet-self and our shepherd-self remind us of this.

Recovering the Capacity to Praise

The shared practice of both the poet and the shepherd is devotion. Night after night, David placed his harp by the window. Day after day, David set out with his flock. Norris writes that while children can praise (again, in the fullest sense of that term) spontaneously, it can take a lifetime for adults to recover this ability. We tend to think that we recover through grace, and maybe sometimes that is true, but the great artists of our time, like Cohen, teach us that it is a practice of daily supplication that help us relearn praise, a praise that as adults will now require more of us.

When I saw him in concert three years ago in Portland, Cohen began the show by telling us that time was short, that he was about to turn 80, that he had promised himself if he made it this far he would let himself start smoking again, and that in any case he suspected this was his last time to roll through town. He promised, “So tonight we are going to give you everything we’ve got.” And he did. His music and presence that night could only be described as devotional. At times, he got down on his knees before his singers and musicians, in supplication. Like an old king who still loved God, maybe more than ever, who recognized the futility of searching for meaning, but was ever more committed to continuing to do it.

Integrating the Poet and Shepherd

We could say the search for meaning – which is a holy search – becomes imperiled whenever the poet-self and the shepherd-self are out of balance. If one is only a shepherd, she will risk being pedantic and overly serious; her ego will get in the way of her true service, and she will forget that each being shares the burden of caretaking – it is not up to her alone. The image of one shepherd over many no longer holds. Similar to how it has been said that the next Buddha is the sangha, the Jewish view of redemption imagines a shepherd-collective, a community of shepherds taking turns taking care.

If one is only a poet, without a good measure of shepherd mixed in, there is a risk the poems will not reach outward and be in dialogue; that they will not intend towards the transformative – which is where all poems must intend, even if they fail. The poet brings to the shepherd an appreciation for the multiplicity of truths, for the impossibility of fixing anything. Without the poet-self, we become ideologues. The shepherd brings to the poet a reminder that too often our search becomes self-serving, discovery of self for its own sake; that others become stepping stones for us on the road to some imagined “actualization.” Often the search for meaning unwittingly becomes a defense against whatever or whoever is quietly sitting across from us in the café, across the table, by the side of the road, the other in our life as it is.

The Secret Chord

As we go through life, it is tempting to think that our search for meaning is a story that never delivered on its promise, or was somehow falsely designed, with many fatal flaws. But maybe the search is simply a force that propels. In truth, there is nowhere else to be than on this search. Everything brings God closer to us, even those things that seem to bring us further away. And the secret chord is ever illusive. It is like the Jorge Luis Borges story of a seeker in search of the one true word, finally discovering it only to hear another word spoken in its place a moment later. Maybe the secret chord that King David and Leonard Cohen sing of is the dawning knowledge that the word is different each time.

Whatever each of us does, whatever our work is, the task is an integration of the poet and the shepherd. One could posit that it was this very soul-weave that led to David’s being chosen as king.

Psalm 88 says “my one companion is darkness.”7I take this to mean our work on the search for meaning is to commit to not only waiting in the darkness, but singing to it. And to not use the not-knowing to abdicate responsibility; to not use the fundamental insecurity of being a human being as an excuse to cease serving or praising. ♦

Endnotes

1Pinsky, Robert The Life of David New York: Schocken /Nextbook, 2005

2I Samuel 16:11

3I Samuel 16:23

4Wieseltier, Leon “My Friend Leonard Cohen: Darkness and Praise” The New York Times Nov. 14, 2016

5Norris, Kathleen The Cloister Walk New York: Riverhead Books, 1996

6Tami Simon interview “The End of your World: An Interview with Adyashanti” Sounds True, June 14, 2011

7Psalm 88:18