“The cinema is truth twenty-four times per second.” —Jean Luc Godard

All movies are an illusion. We think we are seeing motion but in fact we are seeing twenty-four still pictures every second. Half the time the screen is actually black. Yet movies seem so real, and some have the potential to reveal great truth.

In the Hindu tradition, what we perceive of the outside world is called maya, or illusion. It is described as a veil that obscures the truth. But maya also has another aspect, which is the power to reveal the truth. Film and other art forms can embody both aspects of maya.

“What kinds of films do you make?” people often ask me, after I’ve told them that I am a filmmaker. “Documentaries,” I tell them. “Oh, movies about reality,” they say. “True stories.”

The issue of “truth” versus “reality” is a constant tension in creation of any film, especially documentaries. Filmmakers know that every time we make a choice of where to put the camera or when to turn it on or off, we are making choices about subjective perceptions of reality. When we edit, as I did in my latest film, ninety hours of footage down to ninety minutes, we are clearly manipulating reality, or truth.

Like the best storytellers, I don’t let facts get in the way of the truth. This might sound like heresy to some, but it is the nature of art. My motivation is to move audiences: first and foremost, to tell them a great story that holds their interest and attention, and then to put them in touch with some deep truth, to the best of my ability to perceive it and communicate about it. In that way, if the viewer is ready, the film has the potential to transform the way one sees the world and oneself. Paradoxically, to accomplish this I must manipulate reality.

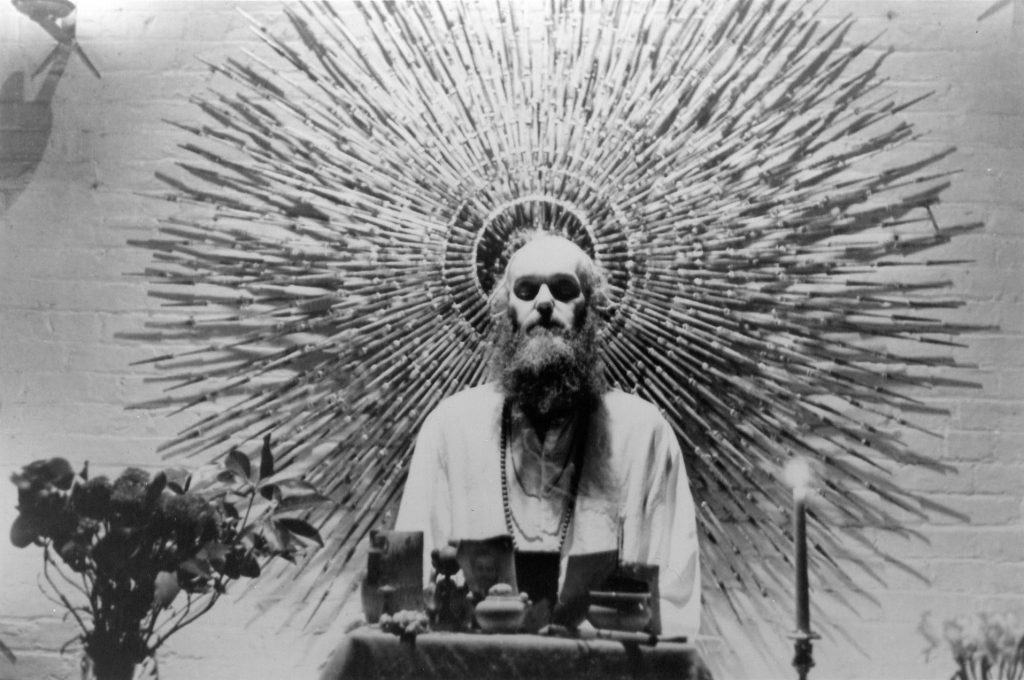

For instance, in my most recent film, Ram Dass Fierce Grace, we filmed a remarkable sequence in which a twenty-five-year-old woman came to see Ram Dass after her boyfriend, her first love, was kidnapped and murdered in Columbia while trying to help indigenous tribes protect their land rights from encroachment by U.S. oil companies. For two and a half hours, we filmed an amazing encounter. In an alchemical transformation, the young woman, Abby, went from grief to faith. At one point in that extraordinary exchange, Abby was crying, Ram Dass was crying, and I was crying. I looked over to my cameraman, and he was crying. Now, as a filmmaker one often has to live on various levels of consciousness simultaneously. So while emotionally I was totally present, at the same time I was also thinking, “I hope this is in focus.” The crew and I felt blessed, not just to be able to witness this amazing scene, but to know that we were capturing it on film, and that we would be able to share a perspective about death, loss, grief, and faith with millions of people, one that might help some of them experience their own suffering in a new way.

In the film, the sequence runs twelve minutes. It is twice as long as any other scene in the film. It is so poignant and delicate that the audience must feel that we captured the interaction just as it happened, that it was unedited. To cut two and a half hours down to twelve minutes and have it seem unedited takes work, lots of hard work—in this case, five weeks of working eight to ten hours a day—so that the sequence feels as though it unfolded that way. In the film, Abby says this, Ram Dass answers that, and so forth. In reality, she says this, and perhaps forty minutes later, he says that. However, juxtaposing these two moments expresses the essence of what happened between them during their interaction, and in that way expresses the truth of the interaction, not the facts.

There is no greater film about the issue of truth than the classic Rashomon by the great Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. Rashomon tells the story of a man, a samurai, leading his wife on horseback through the forest. They pass a highwayman resting by the side of the road. As they ride by, the wind raises the woman’s veil, and the highway man becomes aroused. He must have her. He does. The samurai husband dies.

What makes the film unique is that each of the three participants in the event tells the story of what happened to a judge or inquisitor, and each version is very different, depending on the subjective point of view of the person telling the story. A fourth version of the story is told by a woodcutter, who observes the whole event. The viewer hopes that the woodcutter’s version is that of the impartial observer, that he is telling the truth. However, it becomes clear that his version is also subjective. He exaggerates and edits his on participation. The film never reveals the objective truth of what happened. Each viewer must decide for himself or herself which character is “telling the truth,” or else accept the ambiguity as the truth.

When I wrote “impartial observer” above, I was about to write, “a God’s-eye version.” But perhaps it is the four different versions taken together that constitute the God’s-eye version. Perhaps one would have to include the forest’s point of view as well as that of the birds and insects to really have a “God’s-eye view.”

Rashomon begins in a torrential monsoon rain. The scene where the possible rape and murder occurs is deep in the forest, which itself is like a character. This was a highly conscious decision by Kurosawa. The rain, the wind, the fire. And the forest are all characters in the film. It is as if nature is more than the background in which the human drama takes place. Naure is the Truth, ever-changing and constant. Human truth is all subjective.

All the ancient Japanese religions are rooted in nature. Joseph Campbell used to observe that one of the differences between the Judeo-Christian-Islamic traditions and Eastern traditions is that in the former the world is half good and half evil. One is to identify with the good and try to change the evil. One does not align oneself with nature in that universe—one is baptized or circumcised to separate oneself from it.

In Eastern traditions, one’s goal is to put oneself in accord with nature, to allow things to be just as they are. A Tibetan Buddhist meditation teacher begins every meditation with “Rest your weary minds. Allow everything to be just as it is.” If God is Truth. And the whole of this universe and all the other universes are in God, does that not include greed, sloth, gangsta rap music, slow bank tellers, and mass murderers? Does that not include evil, ignorance, and illusion?

This doesn’t mean that one should become passive and detached. Social action is still important. Acting from compassion to alleviate suffering is worthwhile. So is using art to reveal the Truth. Nature is the Truth is Rashomon. To enhance this truth, Kurosawa manipulated nature to make it seem more real. For instance, the light of the forest scenes is very dappled, black and white and gray simultaneously. The film crew pasted leaves onto a scrim and moved it as a light was shined through it. The dappled light on the actor’s faces makes the scene seem more real. Kurosawa also heightened the rain effect by tinting the water they used.

I once made a film called The Other Side of the Moon, about the men who went to the moon, their journeys, and what happened to them in the twenty years after. For the film, I went down to Houston and spent a week viewing all of the film and video that was shot on the moon. I particularly liked the images of the astronauts falling down, dropping hammers, and playing in the almost weightless environment. I loved the human moments that I had not seen before in the official NASA films.

When I cut those moments into the film, I had a dilemma: when a hammer dropped out of an astronaut’s hand and fell on the ground, should I put in a corresponding sound effect? Actually, there is no sound in the airless environment of the moon. So what was real was to have no sound. However, with the sound effect it felt more real.

I called Alan Bean, who had walked on the moon with Apollo XII. After leaving NASA, he became a full-time professional artist, painting pictures of the lunar landscape. I explained the predicament to Alan. He told me that there was no color on the moon, but that he used a touch of color because it made his pictures feel more real. I left the sound effects in. In art it’s about what feels real and true.

The perception of reality is one of the themes of Ram Dass Fierce Grace. As Ram Dass says, “Our perception of reality is a projection of our mind.” Ram Dass observed this in his early research into psychedelics and the nature of consciousness with Timothy Leary while they were both professors of psychology at Harvard. Then this awareness was enhanced by his experiences in India with his Hindu guru and his Buddhist teachers. In the film, Ram Dass, now confined to a wheelchair, describes how those earlier realizations help him deal with the effects of a massive stroke he suffered in 1998:

I can no longer drive my car. Now, my attendant drives the car, and I sit in the passenger seat. So each time I get in the car to go somewhere, I can either be an ex-driver, who can no longer drive, which will bring up suffering for me on that trip, or I can say, “Far out, I’m being chauffeured!” One brings up suffering, and the other brings up joy. It’s just a projection of my mind on the phenomenon of a trip to the post office.

As an artist, one is always playing with perception. Most of us believe that what we perceive is the truth. “Seeing is believing,” as the expression goes. For instance, have you seen a beautiful sunset recently? Here we are hundreds of years after Copernicus and Galileo, and we are still seeing the sunset. The sun doesn’t set. The earth rotates and eclipses the sun.

Back in the days of Newton, there were absolute laws of nature. Einstein explained that everything is relative.

How we perceive the truth is often influenced by our belief systems. In closed systems of belief, in any orthodoxy, there can be absolute truth. True believers believe that they—and their specific belief system—have a lock on the Truth.

Mahatma Gandhi was once leading a large protest march across India. A few days into the march, he found out that there was to be a great deal of violence, and he abruptly announced that he was ending the march. Some of his followers and supporters said, “But Gandhiji, you can’t call off this march. Many people, from all over India, left their jobs and came great distances to be on this march.” Gandhi replied, “Only God knows absolute truth. I just know relative truth. My allegiance must be to truth, not to consistency.”

Perhaps one of the reasons we feel in the presence of Truth is front of great art is that it takes us out of our belief system and opens us up to deeper possibilities. I believe that each one of us has an honest witness deep inside that tingles when we are in the presence of the Truth. It resonates, just as when one experiences the presence of the divine in nature, in witnessing a birth, a flower, an ocean storm, a volcano, or a tornado. One experiences awe and aesthetic arrest. As James Joyce says, we are put in touch with the Primal Cause of all things, with the Mystery. I’m with Joyce. That is what we strive for. On really good days, we can get close. ♦

Award-winning filmmaker, Mickey Lemle discusses Truth vs. facts in filmmaking from our “Truth and Illusion” Issue (Vol. 28, No. 4). This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.