The American Indian Giveaway

In the old days, no one ever stole. Those who were well off always shared what they had. If there was any thing someone wanted, that person had only to ask the owner and that thing would be given. And no one minded if someone borrowed something and then brought it back to its owner later.

But when the sacred elk dogs, the horses, came, they brought with them new problems. It was not so easy to give away a horse, unless it was a special occasion. As a result, some people began to borrow horses that belonged to others without permission.

They would bring them back, but sometimes many moons passed before that horse was returned. So the matter was brought to the Elk Society and they put forth a new rule for the people:

“From this day on, there will be no more borrowing of horses without permission. If anyone does so, we will follow that person, take back that horse, and give him a whipping.”

Pawnee was young. He did not listen to what was said. He borrowed a horse without permission. The Bowstring Soldiers took after him. Three days out on the trail they tracked him down. They took back that horse. Then they beat Pawnee, destroyed his clothes, broke his saddle and gun, took all that he had and left him there, alone and naked on the prairie.

High Back Wolf came upon poor Pawnee, sitting there and waiting to die. High Back Wolf said, “I am going to help you. That is what I am here for, for I am a chief. But from this day on you must behave right.”

High Back Wolf took Pawnee back to his lodge.

High Back Wolf gave him new clothing.

High Back Wolf said to him, “Outside are three horses. Take your pick and that horse will be yours. Here is the skin of a mountain lion. I give it to you. Wear this skin as proof that your heart is good.”

From that day on, Pawnee’s heart was good.

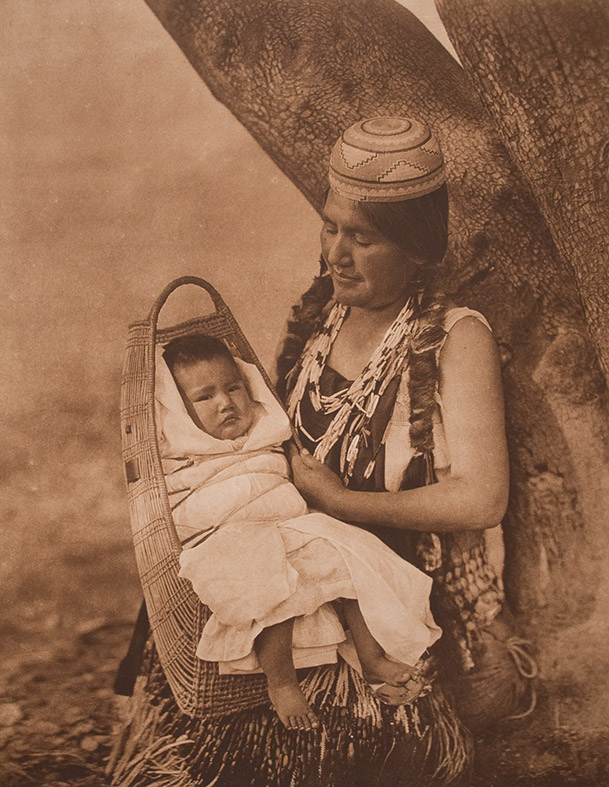

Giving in a sacred way has always been a central part of American Indian cultures. It may be a means of giving thanks, of bringing the people together, of gaining honor, of distributing material goods so that all may survive, of teaching. It maintains the balance that is needed to hold a nation together and to keep an individual in the right relationship within him or herself and with the community—a community that is not just composed of humans, but also of animals, plants, even the stones. For all things are alive.

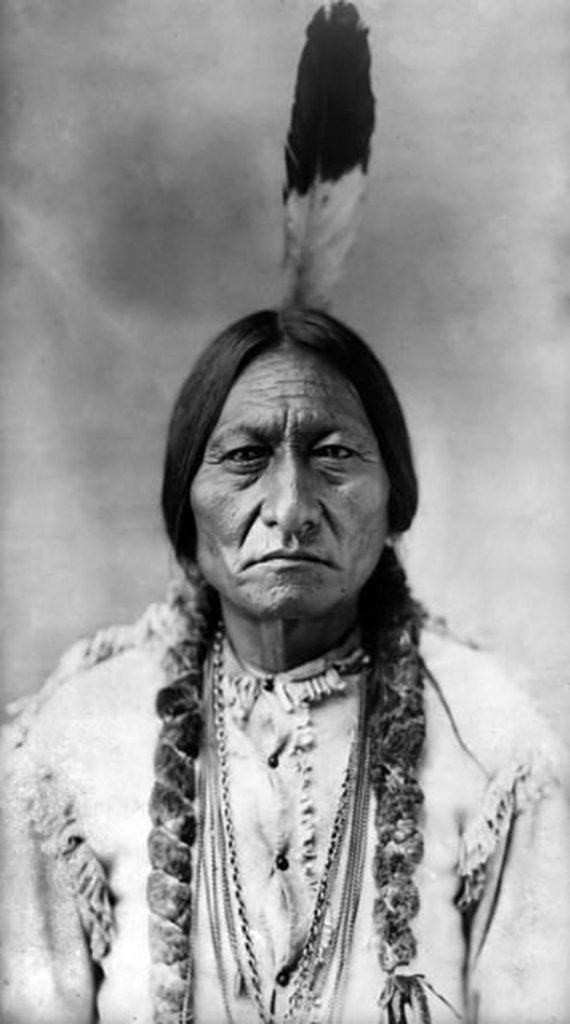

The Tstsistas (Cheyenne) story of Pawnee and High Back Wolf took place in the early part of the nineteenth century. It exemplifies several aspects of the act of giving, as well as pointing out the role of a chief as one whose first thought must be of others, one whose job is to make peace, to be generous. (When the Lakota leader Sitting Bull was asked by a white reporter why his people loved and respected him, Sitting Bull replied by asking if it was not true that among white people a man is respected because he has many horses, many houses? When the reporter replied that was indeed true, Sitting Bull then said that his people respected him because he kept nothing for himself.)

Pawnee is a young man who forgets or has not yet learned that right relationship of sharing. He takes without permission. But when Pawnee is punished by one of the soldier societies whose job includes maintaining order among the people, rather than turning his back on the young man, High Back Wolf—still remembered as one of the great chiefs of that period—engages in a restorative act of giving.

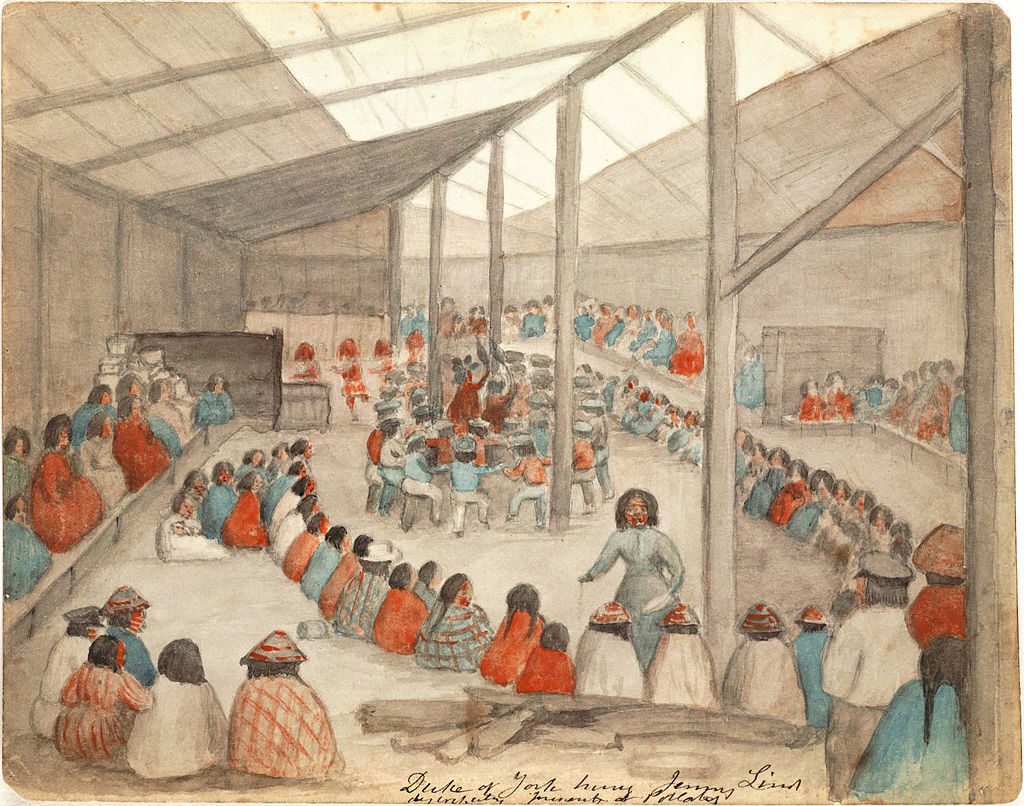

One of the very common practices of virtually every American Indian nation is some form of what is called otuhan in Lakota and in English “a Giveaway.” Even today, if you go to a gathering such as a powwow, a traditional wedding, a naming ceremony, a burial, a Giveaway may be part of the event. It consists of first spreading out a large blanket on the ground. Whoever is holding the event, usually the host family or organizer of the event, places various items, often ones that are handmade, such as woven or skin pouches, beaded key chains, articles of jewelry, on that blanket. Then everyone is invited to come and take one thing from the blanket. Elders come up first, then veterans, women, little children, older children, and finally men. As James David Auden (Distant Eagle) points out in his book Circle of Life, it is not the central participants in the event who are given these gifts, but everyone attending. And the proper way to choose what you accept as a gift is to quietly let the spirit guide you. “Make your choice quickly and step back so that others can come forward.” Further, you do not call attention to what you’ve been given, or show displeasure if someone seems to have gotten something better than you. It is not the gift, but the gestures of giving and receiving that count.

It is a very different sort of giving and receiving from that practiced in majority culture, where the giver is often calling attention to his or her generosity, and the gift is often followed by effusive thanks from the receiver. The strengthening of community is much more important in the American Indian practice, a gifting more akin to prayer than self-aggrandizement and acquisition.

Wopila is another of the Lakota words that means a Giveaway. Dovie Thomason, the well-known Lakota storyteller, once made the mistake of titling a recorded collection of her stories “Wopila.” She took the first hundred or so copies to an event attended by many Lakotas. She arranged her recordings on the table and waited for people to buy them. However, one after another, Lakota people came up, read the title and said “Wopila, oh it is a giveaway. Wopila, good, my sister. Look, our sister is giving away her recording!“ By the end of the event, all of the copies had been given away. Although Dovie did not make any money from selling her tapes that day, she came away from the experience with a smile and a good story.

Giving things away informally is also common in American Indian communities when one has enjoyed good fortune—such as winning the lottery. In most of our American Indian communities such behavior is expected. My favorite story by one of the best-loved American Indian authors, Simon Ortiz of Acoma Pueblo, is called “Howbah Indians.” Howbah means “welcome” in Acoma. The story is about a Pueblo man who manages to purchase a store and then writes on the wall of that store, “Howbah Indians,” to welcome other Indians and let them know the new owner is himself an Indian. It attracts many native customers right away, but none of them pay for the things they get. Soon, the man is forced out of business and the store stands empty. But for many years after, whenever Indians pass by that store they point out those fading words on the wall with pride. It was proof that the man who ran that store, even though he had become “rich,” remained honorable and true to his culture.

I could tell a hundred stories about Giveaways. One of my favorites, and I will not mention the name of the Arapaho family involved because I know they would not want attention called to them, took place not that many years ago. The oldest son of that family had, as many young native people do, joined the United States military and was sent overseas into a dangerous combat zone. As soon as he left, his family began making and collecting star quilts and Pendleton blankets. Star quilts and Pendletons are often used in honoring ceremonies. When someone is being acknowledged for a good deed, one of those blankets is ceremoniously placed around his or her shoulders.

The family of that young man also collected other items of all sorts, spending an immense amount of time and money in the process. Their intention was to have a Giveaway when their son returned home safely. Their acquisition of all those goods was a sort of promise to the Creator that they would honor the gift of their son’s return through the ceremony. Sure enough, when their son did return, the Giveaway was held. Everyone in the community, hundreds of people, came. The family gave away all those blankets, all those goods. Then they gave away their radio, their television, their personal computer, and their truck. Finally, they gave away their house. Everyone was moved by this proof of how much they loved their son, how much they honored the Creator and the community through this giving. And though they had nothing material at the end, they had the satisfaction of having done something truly sacred. And they were cared for by others in the community, as the gift “moved in their direction” in the months that followed, and things were given to them that replaced what they had given.

Wealth, among American Indian people, is not seen as the accumulation and keeping of money or goods or land. The Sacred, by Peggy Beck, Anna Lee Walters (Pawnee), and Nia Francisco (Navajo), contains a wonderfully direct and clear description of what wealth meant (and still means) to native nations.

For most Native American cultures, to be wealthy meant that one had lived well—carefully, with knowledge which had enabled the individual to hunt well, sew well, bring up children well, and if necessary, to fight well, depending on one’s responsibilities. To be wealthy meant that one had much good, enough to give away, to gain respect as a generous person in the eyes of one’s family, kin, and tribe. . . . Most important, to have wealth and power meant that one knew the source of these. One was aware of the equal balance of power and wealth in the things of the universe, and that wealth and power were gifts acquired in one’s lifetime—a lifetime that is very short compared with a lifetime of the world, of a tree, of a river.

American Indian giveaway practices have often been viewed as a threat by government officials, both in the United States and Canada. Government policies in the nineteenth and much of the twentieth century were designed to suppress such activities. In a letter sent to all of the superintendents of the U.S. Indian reservations in 1922, Charles H. Burke, the Federal Indian Commissioner, stated that in order to “foster a competitive, individualistic economic mentality and a Christian faith, using missionaries as aides in this effort” certain practices needed to be eliminated. He ordered that “the Indian form of gambling and lottery known as the ‘iturnapi’ be prohibited.” In an accompanying letter Burke addressed “To All Indians,” he wrote that “you should not do evil or foolish things or take so much time for these occasions. No good comes from your ‘give away’ custom at dances and it should be stopped.”

In Canada, similar rules and regulations were designed to stomp out the potlatch, a complex ceremony that was the main institution for assuming and maintaining social status by the distribution of wealth. Among the Kwakiutl, no person could obtain social status without doing a potlatch. Guests Never Leave Hungry, the autobiography of James Sewid, a Kwakiutl Indian chief who was born in 1910 and lived in British Columbia, talks with great passion and clarity about the difficulty of living in both the white and Indian worlds at a time when such sacred giving was forbidden by the authorities. One of the triumphs of his story is his success in bringing back the custom that had been “outlawed and lost.” “Always Giving Away Wealth” is, in fact, the title of one of his book’s chapters.

In 1992, I was involved in putting together a gathering of American Indian authors that attracted more than three hundred native writers from all over the American continent. When those of us on the planning committee were seeking a name for the event, the choice we ended up making was “Returning the Gift.” It was a title inspired in part by Tom Porter, a Mohawk elder who came to one of our meetings and opened it with the traditional Thanksgiving Address, in which every aspect of Creation, from the Mother Earth, through the Waters, the Plants and Animals, the Winds, the Sun, the Moon, the Stars, the People, and the Creator, are greeted and thanked. It reminded us of all the gifts we have been given, including the ability to express ourselves with words. Our gathering, which took place over a four-day period at the University of Oklahoma, in the heart of Indian Country, would truly be a way to return the gift—to remind ourselves, as native writers, of our responsibility to our communities and to each other. To use our gifts in something other than a selfish way. We needed to not just talk about our work, but to give thanks. When the late Chief Jake Swamp, another well-loved Mohawk elder, wrote a picture book a few years ago that was based on the Thanksgiving address, he chose the title Giving Thanks.

I’ve also heard it said that we need to think of all the gifts we receive as having come from the Creator of all things. Thus it is to the Creator, the Great Mystery, that thanks should be given—not to any human being. We say “Please” to each other and “Thank You” to Ktsi Nwaskw, Gitchee Manitou, Wakan Tanka, or whatever name we have in our many languages for the Great Mystery, the Creator. This may help ensure that those who give do so with humility, with an awareness of the sacred nature of all gifts.

Thus the giver is not calling attention to himself or herself, but to the spiritual power behind it all. Thus both giving and receiving remain sacred. ♦

From Parabola Volume 36, No. 2 “Giving and Receiving,” Summer 2011. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.