Perhaps the most important reason for “lamenting” is that it helps us to realize our oneness with all things, to know that all things are our relatives

―Black Elk1

A saint (is one) who does not know how it is possible not to love, not to help, not to be sensitive to the anxiety of others.

―Abraham Heschel2

This story is so old we don’t know who told it or who it’s about, except that it speaks to all of us. We no longer know if it was a “he” or “she” at the center of the story. No doubt the story has grown for every telling. But for this telling, let’s call our central character Kwun and let her be a heroine.

One day Kwun crossed a valley and stumbled on a bloody scene. An entire village was laid to waste, the people torn apart. Walking among the bodies, her heart was breaking open, enlarging for coming upon the suffering. She was drawn, almost compelled to look inside their bodies and at the same time repulsed by the violence that had opened them. There was an eerie silence steaming along the ground. It looked like the fierce work of a warring clan. Suddenly, Kwun heard a terrible cry from the middle of the scene. She had to pull a dead man aside to find a woman barely breathing, clinging to her little boy who was bleeding from the head. Kwun fell to her knees and without thinking embraced them both, their blood coating her.

As the wind can lift the snow off a branch, the cries altogether can somehow lift the sadness off a broken heart.

The cry of the dying mother was as much from her own pain as from her powerlessness to help her son. When she saw Kwun, her cries grew worse. It was clear she was asking Kwun to take her boy. At first, Kwun shook her head, unprepared for any of this. The dying mother clutched Kwun’s hand and fell away. The boy was unconscious, still bleeding from the head. Wherever Kwun was going before stumbling into the valley, that life, that plan, that dream was gone. It was too late to close her heart and walk away.

She lifted the little, bloody boy and, though he was unconscious, Kwun covered his eyes as she walked over the rest of the bodies, leaving the village. Carrying the boy, she began to cry, feeling for the mother who had watched her man die and her son be bloodied, and feeling for the boy who, if he woke at all, would be all alone. She began to moan as she walked, keeping the cry of the mother alive.

By the end of the day, Kwun managed to climb out of the valley and, exhausted from the tasks of surviving, fell asleep at the mouth of a cave. When Kwun woke, the bloodied little boy had died in her arms. She didn’t know what to do, though there was nothing to do. She held him for a long time, then opened his little eyes, wanting to see what was left within him. And looking there, she began to feel the cries of the world, long-gone and long-coming. It overwhelmed her as she felt a pain that almost stopped her breathing. But she kept rocking the little one, certain the world would end if she put him down. Without her knowing, she began to hold the broken that would fill eternity, long before they would suffer: the stillborn, the betrayed, the sickly, the murdered, the thousands left to mourn. Letting them move through her began to open her heart like a lotus flower. And the cries of the world, though she couldn’t name a one, made her stronger. At last, she fell asleep again. While she slept, Kwun became a source of healing. When she woke, she spent her days touching the wounded, holding the dying, and keeping the cries of the world alive. The cries became a song she didn’t understand, other than to know that, as the wind can lift the snow off a branch, the cries altogether can somehow lift the sadness off a broken heart.

Wherever We Go

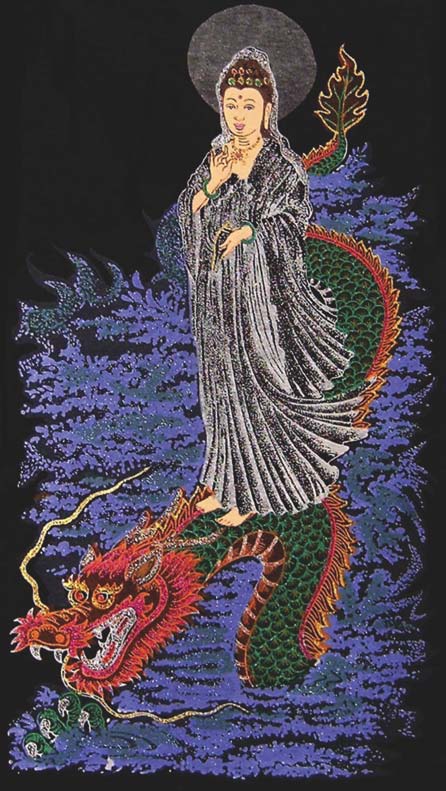

Kwun may be an ancestor of the Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara, also known as Kuan-yin, whose name means hearing the cries of the world. We’ll never know, but like rivers joining in the sea, stories coalesce and merge over time into the one story that remains, the one we each wake to, surprised it is ours.

Wherever we go, wherever we wake, we are challenged like Kwun to hear the cries of the world very personally. The cries are unending and overwhelming, and our noble charge to hear them—to hold them and keep them alive—is how we keep the life-force we need lit between us. As Black Elk says at the beginning of this chapter, the reason to lament is that it helps us to realize our oneness with all things, and to know that all things are our relatives.

This has never been easy; for grief is so challenging that it often blinds us to its importance. As the Sufi poet Ghalib says, “Held back, unvoiced, grief bruises the heart.”3 Try as we will, we can’t eliminate or solve these cries, for they are the song of existence. When we try to mute or minimize the voices of suffering, we are removed from the life-force that keeps us connected. If we get lost in the cries, we can drown in them. So what are we do with them? What is a healthy way to relate to them?

I’ve found that whatever I go through opens me to what others have gone through. This is the gut and sinew of compassion. Our own ounce of suffering is the thread we pull to feel the entire fabric. Having pinched a nerve in my back, I can feel the steps of the elderly woman who takes twenty minutes to shuffle from the bread aisle to get her milk. Having lost dear ones to death, I can feel the weight of grief that won’t let the widower’s head lift his gaze from the center of the Earth where his sadness tells him his wife has gone. Having tumbled roughly through cancer, I can feel fear arcing between the agitated souls who can’t stand the wait. The fully engaged heart is the antibody for the infection of violence in the waiting room. I’ve begun to meet the cries of the world by unfurling before them like a flag.

I was in college, sitting with my grandmother in her Brooklyn apartment, when she fell into another time and left the room. She’d left an old photo on the table. It was of a young family posing in a studio in 1933. The parents seemed to have the whole world ahead of them. When she returned, I asked. It was her sister and brother-in-law and their small son. They lived in Bucharest. There was a long pause and an even longer sigh, “We saved and sent them steamship tickets to come.” She dropped her huge hands on her lap, “They sent them back, and said Romania was their home.” They died in Buchenwald.

It was pulling that thread that opened my heart to the cries of the Holocaust and from there, to the genocides of our time. Those cries plagued me, wouldn’t let me sleep. In time, I realized I was opening myself to the enormous suffering of history for no other reason than to feel the complete truth of who we are as humans. This is impossible to comprehend, but essential to let it move through us, the way the cries of the world moved through Kwun so many centuries ago.

Each of us must make our peace with suffering and especially unnecessary suffering, which doesn’t mean our resignation to a violent world. For the fully engaged heart is the antibody for the infection of violence. As our heart breaks with compassion, it strengthens itself and all of humanity. Can I prove this? No. Am I certain of it? Yes. We are still here. Immediately, someone says, “Barely.” But we are still here: more alive than dead, more vulnerable than callous, more kind than cruel— though we each carry the lot of it.

That we go numb along the way is to be expected. Even the bravest among us, who give their lives to care for others, go numb with fatigue, when the heart can take in no more, when we need time to digest all we meet. Overloaded and overwhelmed, we start to pull back from the world, so we can internalize what the world keeps giving us. Perhaps the noblest private act is the unheralded effort to return: to open our hearts once they’ve closed, to open our souls once they’ve shied away, to soften our minds once they’ve been hardened by the storms of our day.

Always, on the inside of our hardness and shyness and numbness is the face of compassion through which we can reclaim our humanity. Our compassion waits there to revive us. When opened, our heart can touch the Oneness of things we are all a part of. Then, we can stand firmly in our being like a windmill of spirit: letting the cries of the world turn us over and over, until our turning generates a power and energy that can be of use in the world.

Running from the Cries

Sometimes, being alive is so hard that we think it would be better to avoid all the suffering. But we can’t, anymore than mountains can avoid erosion. And there is a danger in running from the cries of the world. In extreme cases, our refusal to stay vulnerable can twist into its opposite in which we strangely get pleasure from the suffering of others. The German word Schadenfreude means just this. Such perverse pleasure derives from the utmost denial of being human; the way running from what we fear only makes us more violently afraid. Severely renounced, the need to feel doesn’t go away, but distorts itself. In the same vein, the term “Roman Holiday” refers to the grisly spectacle of gladiators battling to the death for the pleasure of the Roman crowd.4

This danger is insidious in today’s rush of incessant news coverage twenty-four hours a day. We can be brought into heartbreaking kinship in a second, as with the September 11th attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City or the horrific massacre of twenty schoolchildren in Newtown, Connecticut. And like Kwun in the ancient tale, we can be compelled to look at the raw insides of tragedy to glimpse how tenuous our time is on Earth, while being repulsed by the violence that opens such a stark revelation. But if not careful, the endless replaying of tragedy from countless angles can push us over the line till we fall prey to that perverse pleasure of the Roman crowd.

To view tragedy beyond our feeling of it adds to the tragedy and turns us into dark voyeurs. Yet just as Kwun’s rocking of the lifeless, little boy enabled her to hear and feel the suffering of those yet to come, keeping our heart open to one torn life can enable us to hear and feel the cries of all who suffer.

Which side of reality we dwell in determines whether we are offspring of Kwun and Kuan-yin, descendants of those who keep the cries of the world alive, or offspring of the warring clan, descendants of those who gut whatever is in the way, who cheer the bloody spectacle. These twin-aspects of life are closer to each other than we think. The seeds of both live in each of us. It is our devotion to staying vulnerable that keeps us caring and human.

True connection requires that a part of us dissolves in order to join with what we meet. This is always both painful and a revelation, as who we are is rearranged slightly, so that aliveness beyond us can enter and complete us. Each time we suffer, each of us is broken just a little, and each time we love and are loved, each of us is beautifully dissolved, a piece at a time. We break so we can take in aliveness and we dissolve so we can be taken in. This breaking and dissolving in order to be joined is the biology of compassion. The way that muscles tear and mend each time we exercise to build our strength, the heart suffers and loves. Inevitably, the tears of heartbreak water the heart they come from, and we grow.

Our fear of such breaking and dissolving keeps us from reaching out, from stopping to help those we see in pain along the way, telling ourselves it’s none of our business. But no one can sidestep being touched by life and, sooner or later, the fingers of the Universe poke us and handle us and rearrange us. Running from the cries of the world makes the Universal touch harsh. Leaning into the sea of human lament makes the Universal touch a teacher. Hearing the cries of the world causes us to grow, the way every power opens for receiving the rain.

What Are We to Do?

The Life of Kwun and Kuan-yin calls, their simple caring in our DNA, though it’s never easy to cross into a life of compassion. Since the beginning, we have all complained, when weary or afraid of the power of feeling, that we have a right to happiness. Can’t we ever look away? Must we always feel guilty for those who’ve suffered beyond our control? But guilt is the near-enemy of true kindness. It won’t let us look away or let us give our heart to those who suffer because our lives will change if we do.

No matter how we fight it, life always has other plans and we are faced, when we least expect it, with the quandary of living softly in a beautiful and harsh world. Under all our goals and schemes is the sudden need to help each other swim in the mixed sea of joy and sorrow that is our human fate.

The truth is: my suffering doesn’t have to be out of view for you to be happy, and you don’t have to quiet your grief for me to be peaceful. Allowing our suffering and happiness to touch each other opens a depth of compassion that helps us complete each other.

There are always things to be done in the face of suffering. We can share bread and water and shelter in the storm. But when we arrive at what suffering does to us, there is only compassion—the genuine, tender ways we can be with those who suffer.

Some days, I can barely stand the storms of feeling and fear civilization will end, if we can’t honor each other’s pain. But in spite of my own complaints and resistance, I know in my bones that openness of heart makes the mystery visible. Openness to the suffering we come across makes our common heart visible. If we are to access the resources of life, we must listen with our common heart to the cries of the world. We must forego our obsession with avoiding pain and start sensing the one cry of life that allows us to flow to each other. ♦

ENDNOTES

1. Joseph Epes Brown, recorder and editor, THE SACRED PIPE, BLACK ELK’S ACCOUNT OF THE SEVEN RITES OF THE OGLALA SIOUX, (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953), 46. Black Elk was a Native American sage of the Oglala Sioux.

2. Abraham Joshua Heschel, THE EARTH IS THE LORD’S: THE INNER WORLD OF THE JEW IN EASTERN EUROPE (Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2001), 20.

3. Mirza Ghalib, translated by Jane Hirshfield in THE ENLIGHTENED HEART Stephen Mitchell, ed. (New York: Harper, 1989), 105.

4. The barbaric gladiator combats were extensively showcased in the Roman Coliseum, peaking in popularity between the first century BC and the second century AD. The Coliseum was built just east of the Roman Forum. Construction started in 72 AD under emperor Vespasian and completed in 80 AD under emperor Titus. Seating fifty thousand spectators, the amphitheater was also used for public spectacles such as mock sea battles, animal hunts, and executions.

From Parabola‘s 150th issue “Heaven and Hell,” Summer 2013. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.