“As I commute to work every day, I leave behind a quiet country road for a highway that takes me to the city. Nature still persists for a while, then gradually thins out, as I draw closer to a mechanical environment that encroaches on my whole being with its steel façade, its noise and quickness.

I have left my solitude. For the next seven or eight hours of my day, I move about among hundreds of people and become just another face in the crowd. I may have a private moment with a few persons, but try as I may, I find it difficult to overcome the feeling of loneliness which lingers behind most human transactions. Frustrated by a furtive glance from a colleague, I discover that to attempt a meaningful communion with him becomes an impossible task, beset by astonishing difficulties. I cannot help feeling like Coleridge’s ancient mariner who is surrounded by water and is dying of thirst.

I have worked hard for this arrangement, dividing my time between the country and the city. I still need my job in the city, but I find it increasingly difficult to leave behind a natural way of life and enter an unnatural and at times cruel environment which demands such unnatural responses in the name of survival and industry. In an age that prides itself on its achievements in the fields of communication technologies, men and women are suffering from loneliness and solitude as never before, due to a simple lack of communication.

Solitude is not unique to our technological age, though technology does encourage a self-sufficient and emotionally sterile way of life. What is unique is the clinical aspect of this contemporary solitude, which often degenerates into a profound depression. People are prone to this depression because they realize in their innermost beings the futility of leading a life filled with solitude that does not lead anywhere, a solitude which is meaningless and unproductive. This solitude is reflected in “the jumbled heap of murky buildings” that Keats spoke of, and in the inhumanity of the machinery dominating the landscape.

This solitude can be compared to something very different that Henry David Thoreau wrote about when he temporarily left his community and for a period of two years withdrew to Walden Pond, in order to bear witness to a more authentic way of life, true to the pioneering spirit of the pilgrims to this continent. Thoreau wanted to prove that although we are born in a community which shapes and nurtures our whole being with its traditions, we have a duty to respond to an inner call for solitude and authenticity and to undergo a series of trials in order to be able to re-enter and serve the community on a more real and selfless way. We can only be of use to our community if we withdraw from it and start a pilgrimage of self-discovery. It is only be retreating from the community and distancing ourselves from it that we come to an understanding of ourselves and our potential, since “we are for the most part more lonely when we go abroad among men than when we stay in our chambers.” This understanding brings about a transformation of our old selves, previously defined–ill-defined perhaps–by the community which gave us our identity, and this transformation allows us to realign ourselves to the world beyond the confines of our community and to rediscover our place in it.

Only in this sense can our solitude bear fruit and can our solitary state become public domain. In any other respect our solitude is unproductive and leads merely to depression. Many original thinkers agree on this beneficent attribute of solitude. One of the most successful essays of Montaigne explores the positive aspects of solitude from this perspective. He is critical of Cicero, whom he accuses of using solitude for its own sake and retiring from public affairs to achieve immortality through his writing.

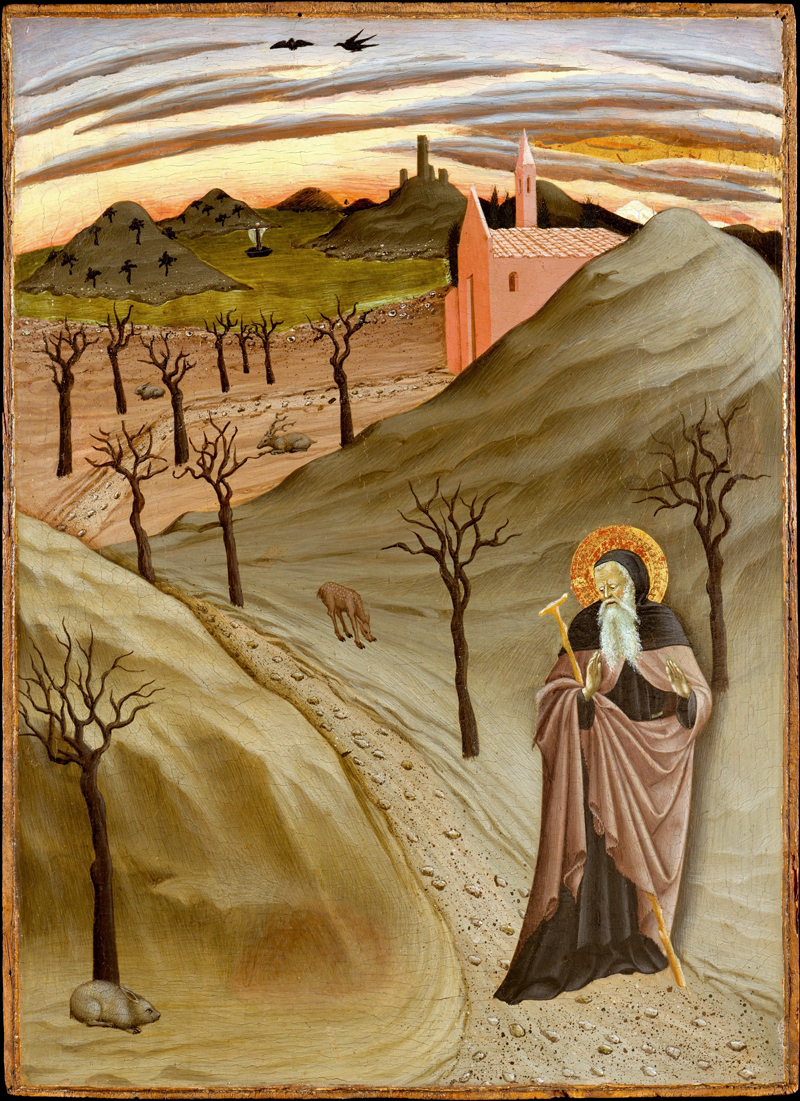

Indeed, the solitary who does not return to his community, to enlighten and serve it in a selfless way, may be regarded as having failed in his mission and purpose in life. The greatest ascetics did not hesitate to return to the world, having forsaken it and lived in solitude for several years. St. Antony of Egypt, an inspiration to anchorites of all time, returned to Alexandria after twenty years of seclusion spent in a ruined fortress in the desert. Then, realizing that to continue living in the city would be comparable to the life of a fish on dry land, he decided to go back to the desert, but to make a commitment to see all those who flocked to his cell.

The journey of withdrawal from the world to the desert should not be viewed as an end in itself. The hermit who retires from what he perceives to be the arid desert of this world enters the fertile desert of his soul, the first stage in his quest of self-discovery in relation to an ultimate reality. The hermit–from the word for erimo, desert–is deserting the worldly pursuits of wealth and pleasure in order to attend to attend to the affairs of the soul, which can only be realized through the trials encountered in extreme poverty and solitude. He abandons, like a deserter from the army, the battleground of worldly pursuits, to struggle with the army and legion of demons–the passions–who are obscuring his quest for the ultimate things necessary for his salvation. In this quest he is alone, monachos, a monk.

In scope, his labors do not differ from the traditional here’s exploits; the only difference is that the ascetic’s works are actual, contrasted to the symbolic labors of the hero.

Heroes from classical mythology and religious legend likewise must chart a common route, beginning with initiation, a journey, and various trials, in order to deliver themselves and their communities from the evil that is plaguing them. Hercules’ slaying of the Hydra is comparable to St. George’s slaying of the dragon. Both have a common purpose and require a common symbolic interpretation: the heroes rid the world of evil, exorcising ills that prevent it from being a blessed and hospitable domain. Both stories share a common vocabulary, describing in identical terms a common search for truth.”♦

—An excerpt from Lambros Kamperidis, “Surrounded by Water and Dying of Thirst,” withdrawing from the world as preparation for re-entering the world, PARABOLA, Volume XVII, No. 1, “Solitude and Community,” 1992.

Art Credit: Saint Anthony Abbot Tempted by a Heap of Gold, Tempera on panel painting by the Master of the Osservanza Triptych, ca. 1435, Metropolitan Museum of Art.