Memory of Loss

I grew up in a rural environment, close to nature, observing the changes of seasons and weather, the changes of light on the fields, and in the woods. I remember walking through my father’s apple orchards in spring — the trees full of blossoms, the hum of bees, the warmth of the sun.

Our cobblestone farmhouse, built in the early 1800s, was constructed with small palm-sized stones naturally rounded by water from the shores of Lake Ontario. One hundred acres of apple trees surrounded it. The farm was in a rich agricultural area of Dutch farmers, a strip of land on the south shore of Lake Ontario which was a fruit belt of apples, peaches, and cherries. In addition there were areas with rich black soil for growing celery, lettuce, cabbage and carrots. Dairy farms were numerous. Over the years our orchards were turned into pastures for dairy cattle. My sensibility as an artist is woven from a deep connection to this childhood of the farm and the animals. I slept in a tree house in summer, and spent a great deal of time alone in the fields and woods. I built little nature worship shrines of sticks, mud and stones.

Small farms cannot survive today. This is the era of agribusiness. In my childhood farms were controlled and operated by one family. Enormous barns, empty and decaying relics of time gone by, are scattered throughout the countryside in upstate New York.

I move to New York City to study art.

We lose our family farm.

My father dies.

As an art student I loved the biomorphic paintings of Gorky, Pollock, de Kooning, and the early works of Rothko and Newman, and the paint charged vista of surface, light and color of Abstract Expressionism.

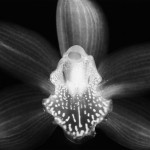

The move to the largely man-made urban environment of New York City intensified my sense of loss of nature. My photographs of vegetation – plant forms and flowers – are a metaphor of this sense of bereavement.

I do not photograph these forms with a camera. They are made by the plant form being placed in the head of an enlarger, on a piece of glass. Light passes through both the vegetation and the lens to the surface below. This is a different kind of light than the reflected light used by cameras containing film. The light of my photographs seems to emanate from the image itself, in much the same way as the light which comes from within the accumulations of paint in a painting.

____________________

Amanda Means received a BA from Cornell University and an MFA in Photographic Studies from SUNY Buffalo. Her work is widely collected, exhibited and published.

Collections include the Whitney Museum of American Art; The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; The Albright-Know Art Gallery; The Los Angeles County Museum of Art; MIT List Visual Arts Center; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Exhibitions include The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The International Center for Photography, NYC; The Harvard Museum of Natural History; The Center for the Arts, Wesleyan University; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; and Dorsky Gallery, NYC.

Selected publications include: Parabola Magazine; The New York Times; BOMB Magazine; Oprah Magazine; The New Yorker Magazine; Exploring Color Photography, McGraw-Hill; pdn; 2wice Magazine; Photography’s Antiquarian Avant-Garde – The New Wave in Old Processes, Harry Abrams.

Amanda is a master printer, a Contributing Editor for BOMB Magazine and a Trustee for the John Coplans Trust. She lives and works in Beacon, NY.

Visit: Amanda Means Photography.