One August day recently in Northern California, Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee sat down with Parabola in to speak about free will and destiny. The English-born Vaughan-Lee is a Sufi mystic and lineage holder in the Naqshbandiyya-Mujaddidiyya Sufi Order and the founder of The Golden Sufi Center. Sitting in a big, sun filled room, surrounded by people from around the world, all gathered for a morning meditation, he spoke of his unusual destiny, the journey of his lineage of Sufism to the West, and of our common destiny on an Earth in crisis. Vaughan-Lee is the author of Spiritual Ecology, Fragments of a Love Story, Darkening of the Light, and other books. His most recent book is For Love of the Real: A Story of Life’s Mystical Secret. For more information, please visit www.goldensufi.org.

—Tracy Cochran

Parabola: We came to learn about your extraordinary journey and what it has shown you about free will and destiny. But there will be another question reverberating under all my other questions.

Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee: Ask away.

P: You have written that you reached a point where the journey itself turned out to be illusory. I was left with the question, why do we need to have this “I”? Why do you—I, any of us—need it? You have a taste of the infinite and wake up in the morning and the “I” is still there.

LVL: It’s back there again, yes.

P: Can you tell us about your journey and about how you experience free will and destiny? How did you get from being where you were to where you’re sitting right now? And along the way, would you carry this deeper question, about the purpose of the “I”?

LVL: I will try to answer that. As I’ve grown older I’ve seen my life more and more in terms of stories, and one thing I really like about Parabola is that Parabola tells stories.

I was a middle-class English schoolboy in the 1950’s, sent off to boarding school at seven years old—lots of sports, cold baths, Latin and Greek. Reflecting back, nobody ever asked me what I wanted. That question never came up. It was a very programmed existence, and so in that sense there was not much free will. It was somebody else’s story, not really my story. Then one day when I was sixteen years old, suddenly there was another story. It happened in the English subway. A boyfriend of my elder sister, who was an American, lent me a book on Zen, which was becoming popular at the time, and I read a Zen koan: “The wild geese do not intend to cast their reflection, the water has no mind to receive their image.” Suddenly and inexplicably, rather than this very grey story of boarding school, there were colors, suddenly there was joy, suddenly there was magic present. It was as if somebody had said, “turn the page.”

I started to meditate and found myself in completely other realities, in the vast emptiness beyond the mind—a feeling of total freedom. Maybe that was a first finger of destiny, the first touch of a completely different story that had nothing to with my background, nothing to do with the life I knew. I looked for a teacher and I met a few. I met Krishnamurti whom I found quite extraordinary. He gave me a very powerful experience, but no way to really live that experience.

P: In the course of meeting him you had an experience?

LVL: Yes, he said there is this place of complete freedom that is beyond the mind, beyond the personality. This was in Brockwood Park in England, where he used to come every summer. I was eighteen years old, and I remember it was a beautiful English summer morning. I had spent the night in a field in a little house I made for myself with hay bales, and then I went to hear him talk and he took me into this space of complete and total freedom. He said there is no path, there is no way to get there, it just happens—but suddenly there was another reality present, completely different than anything I had known before. I went home—my father had a house in the countryside in Somerset—and I was just sat there in a state of complete awareness for a few weeks until it was a little bit too intense.

Then I met a Zen teacher, and I also studied with Keith Critchlow, who was one of the first teachers of sacred geometry. We went to Chartres Cathedral, which was an extraordinary experience. I spent two weeks in Chartres Cathedral, one of the great spiritual buildings of our European heritage, which in medieval times had a mystery school. I studied the Chartres maze, and had an inner experience of the reality of its esoteric meaning. But still something was missing. I actually went to an astrologer who later became a very well-known Kabbalistic teacher, Warren Kenton. He did my chart. I don’t know much about astrology, but there is something in astrology called a “Finger of Destiny.” It’s called a yod, and they are quite unusual, and I actually have three of them in my chart, which means I have very little choice in my life. It’s as if there are certain forces that determine how I’m going to live.

Kenton told me that I needed a meditation teacher if I was to go further, and then destiny stepped in or tradition stepped in. One evening when I was nineteen years old, I was invited to a talk on the esoteric dimension of mathematics in South Kensington Library. Sitting in the row in front of me was an old lady with her white hair tied up in a bun. After the talk I was introduced. She gave me one look with these piercing blue eyes and I had the physical experience of becoming a piece of dust on the floor. I had no idea what it meant. I had no idea what was happening. She invited me to her meditation group, and then another story began—I became part of a very ancient story.

Years later I discovered the Sufi saying that the disciple has to become less than the dust at the feet of the teacher. The experience of becoming a speck of dust on the floor referred to a whole tradition of what happens to the disciple in the hands of the teacher. I knew nothing at the time; I didn’t study Sufism. Irina Tweedie, who was the white-haired woman with piercing blue eyes, didn’t even teach Sufism the way we understand teaching. But looking back it was like another whole story had begun—a completely different book. I wonder if it was really my story because, in a way, it was also her story that began twelve years earlier when, in her fifties, she arrived in a northern Indian town called Kanpur. Leaving the railway station she got into a horse-drawn carriage, a tonga, and went to meet a guru. She arrived, hot and dusty from the journey, and coming towards her from a white bungalow down to the gate was a tall Indian man with a long grey beard and blazing dark eyes. He greeted her and told her to come the next morning, when he asked her “Why did you come to me?”—the traditional question that the teacher asks a would-be disciple.

P: That exact phrase?

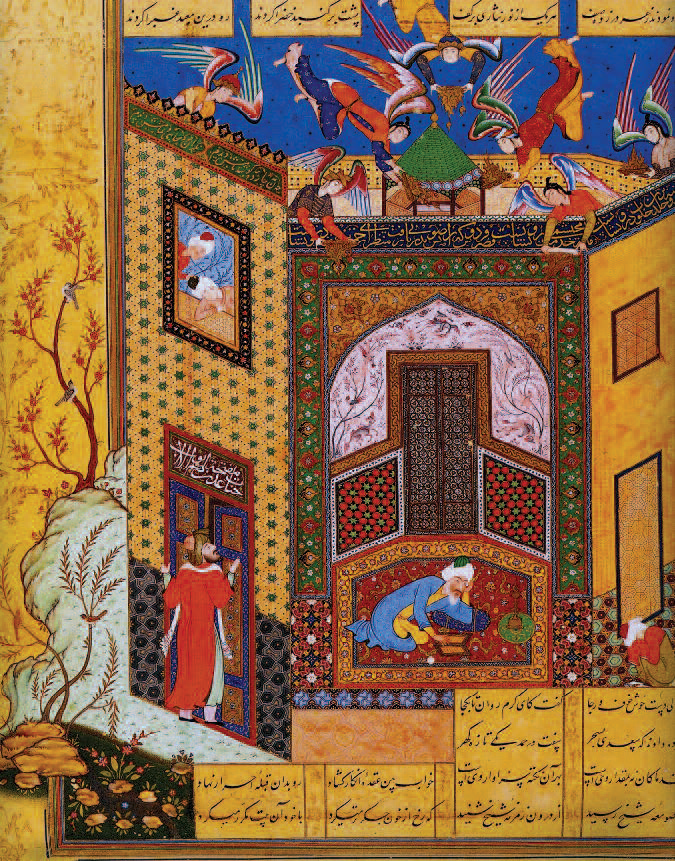

LVL: That exact phrase. This belongs to another whole story and a whole tradition and a whole destiny, which actually began many centuries before when one of the early Sufi masters, Yûsuf Hamâdanî, set out from Baghdad with twelve friends and travelled to Bukhara, where he was to meet ‘Abd’l-Khâliq Ghijduwânî, the founder of the Naqshbandi tradition. Their meeting began the story and destiny of the Naqshbandi path, transmitted from teacher to disciple, which continued many centuries later with this meeting between Irina Tweedie and her Sufi sheikh, Radha Mohan Lal, through which this particular Sufi path came to the West.

P: Did you ever speak of the experience of feeling like dust at her feet? I’m wondering if she felt the same way when she met her teacher.

LVL: The experience she had was that something in her instinctively came to attention before him, she knew she was in the presence of a Great Man. Where this comes from, one doesn’t know because it’s such an old story. This English schoolboy who had a few experiences of meditation, who met a few spiritual teachers, suddenly stepped into the pages of a very old book and suddenly that book became my story. Again what has it to do with me? Even looking back now forty years, I wonder. Suddenly I was in the hands of an ancient tradition and I had no knowing about it.

P: Why you?

LVL: Yes! What was this? And it started to do things to me, to change me, and in a way my life since then has been living this story or this destiny. I had a very dramatic spiritual experience when I was twenty-three years old. One summer afternoon, after a very intense inner time, I was woken up on the plane of the Self. I was woken up into this completely different dimension—a dimension of love, of light, of Oneness, of a completely different state of consciousness. Nobody had told me about it before; I never read about it, and it completely shocked me. I didn’t know what to do. Luckily my mother offered to look after me. She cooked for me. I didn’t eat very much, and I would just sit there in my room. Sometimes I would pray all night, sit all day, there was no time, there was no space. This went on for a few months.

Then at the beginning of January, I had a dream and in this dream I was shown a book for the year. One of the things about stories or destiny is that there is a book of our life and some of it is written and some of it we write ourselves. What has been written, which we have to live, is what one would call one’s destiny; what we get to write ourselves is, I suppose, free will. That January I was shown the color of the year, which was light blue, and I was told it would be quite an easy year. I also saw written in the book of the year that I would have my heart’s desire. I knew what my heart’s desire was when I had the dream because I had already fallen in love with a young woman sitting across from me in the little meditation room where Mrs. Tweedie used to live. In the kind of sense of humor that destiny sometimes has, this was January and I had to wait until the middle of December for my heart’s desire to be fulfilled. But, again, these are forces of destiny. I fell in love, we had a relationship and got married. We had our first child, my son Emmanuel; a year and a half later our daughter was born. Then again in a strange play of destiny that never occurred to me, I ended up buying a house with upstairs and downstairs apartments, and invited Mrs. Tweedie to live downstairs as she needed a place for the group. It kind of reminds me of the story of the Zen student who, very lovingly builds a beautiful house and he’s so happy about this house that he invites his teacher, a Zen Roshi, to come and see it. The Zen Roshi comes in and says, “Very nice house, I will live here.”

P: That story echoes what you said about feeling like dust at the feet of your teacher. Many people in the West, certainly here in America, have this longing to truly be seen and loved, and this can so easily turn into an ego-fantasy—at last a great teacher recognizes your true wonderfulness and will now single you out and elevate you to the position that you deserve, beside them. You describe a very opposite experience, of your ego being kind of pushed out of the way—your fantasy plans for yourself disrupted.

LVL: My son Emmanuel said the first words he ever remembered were, “Shh… they’re meditating.” We lived upstairs and the group met downstairs. Meeting as a group has been a central part of my story, my destiny, and it’s not something I would even have dreamt or have chosen. Mrs. Tweedie could connect with her teacher, whom she called Bhai Sahib (elder brother), in meditation. When she was with him in India, he trained her so that he could reach her in meditation after he died. This is very much part of the Naqshbandi tradition (it is called an Uwaysî connection). Little did I know that they had plans for me. They never told me these plans. She said years later that when I first came to her group she was told in meditation that he would look after me. That’s why I said my story is very much her story, and it is also her teacher’s story, and it’s the story of bringing this particular Sufi tradition to the West. That was her destiny that began when she met him, after she had lived a very full life, and it was my destiny before I got the chance to live what is called a full life.

There were these little seeds. For example, when I was thirty years old, I was a high school English teacher, which I really enjoyed. I taught Shakespeare. I taught poetry. I was never very good at teaching spelling. The girls I taught knew I wasn’t really an English teacher. I thought I had my profession, I’d studied it in college. But they said “Mr. Vaughan-Lee, we know you’re not really an English teacher; you’re not like the other teachers.” I didn’t really know what they meant but one day I was sitting at Mrs. Tweedie’s kitchen table and in passing she said, “Oh, your life will change completely in six years time,” and that’s all she said.

P: Just in passing?

LVL: Just in passing. Yet again there was this very subtle but explicit turning of the page of the book that I had to live, which had to do with my destiny in America. In the summer of 1987 Irina Tweedie came to the Bay Area to lecture. Her book Daughter of Fire had just been published. I first came to California in February that year to arrange her lecture tour for her. I had no interest in America before. I was interested in the Far East but not in America. One day I drove across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco to Marin County, and I stopped and went for a walk on the Marin Headlands. It was a beautiful sunny day, and suddenly I knew that this is where my life’s work would take place. I just knew it.

Suddenly destiny was again present and it just spoke to my soul, or sang to my soul, and four years later, low and behold, I found myself living here. It wasn’t what I’d planned. We had a house in London. My wife in particular looked after Mrs. Tweedie. We looked after the group, and really we thought we would look after her until she died. She was old then, and we thought that our lives’ work was to look after her. We had been looking after her for eleven years. Then one June morning at about two in the afternoon, I was standing in my kitchen looking out at the lovely garden. Mrs. Tweedie planted the flowers, but I was very proud of my lawn without weeds, an English lawn, and suddenly I was hit by this energy. It came—whoop—it was so strong it almost threw me on the floor, and it shifted my consciousness from one place to another. I knew at that moment it was time to go to America. I went downstairs, went round through the garden gate, knocked on Mrs. Tweedie’s french windows and told her. We were both a bit shocked. I said we’re going to be leaving in two months time.

P: That just welled up inside, the two months?

LVL: We had to get the kids into school, and we had to come here at the beginning of August so we could settle before the school year began. We had two months to pack everything up and find somebody to move into our apartment to look after Mrs. Tweedie and we turned up here with a suitcase each. What is interesting is that when you are taken by these forces, somehow you don’t think about what it means. There was no reflection involved. I didn’t know what I was doing in America. I knew this was where my life’s journey had taken me. We moved here in the hills beside the ocean; a friend kindly rented us a house.

Looking back, there were these threads of destiny that were being woven into our life. For example, in 1988, Mrs. Tweedie decided that Anat and I needed a honeymoon. When we were married Anat was pregnant and I was at school and we didn’t have a honeymoon. As in the Indian tradition people used to leave envelopes of money on Mrs. Tweedie chest of drawers—it was in the days before we had any organization—and somebody had left an envelope of money on her chest of drawers and she gave it us. “Go have a honeymoon” she said, and she suggested to us where to go. One of the places was Berkeley. One day we drove out to the coast and ended up having a very nice meal in a restaurant here and Anat liked the area very much. She felt the people had a relationship to the place and the land. They knew each other in the supermarket. When we went back Anat told Mrs. Tweedie about it and she said “Oh that place has a very good vibration. You should live there.”

P: In minds of most people, fate is what happens to you and destiny is your highest human potential. Your life has been guided by the deliberate conscious influence of Sufi masters, who arranged to remain available to you after their death. Two questions come up: First, does everyone have a destiny? Second, how do you see your special destiny? Your life has been guided by extraordinary forces—by the conscious influence of great Sufi masters. Why were you singled out? But again, another way to understand destiny is touching our highest human potential in moments—moments of waking up, of opening the heart.

LVL: I will try to answer both these questions. The soul comes into incarnation with a purpose, with an imprint—one would call it the destiny of the soul. The soul then aspires to attract the right environment to live out the destiny of the soul. For most people it’s a very broad canvas. The outline of the story is there but the pages are left blank and there are different ways to live their destiny. For example: a friend of mine who grew up in a small town in Ireland had a very domineering mother. One day she had a dream in which her mother said very clearly, “My destiny was to have five children. Your destiny is to realize the Truth.” She had five children, and so she lived out that destiny.

My friend is driven by another force that pushes her towards the Truth. We work with dreams, and she had a very early dream in which she met our teacher, Radha Mohan Lal, Irina Tweedie’s Indian teacher, and he held out his hand and there was a veil hanging from his hand. He lifted it for a moment and behind the veil there was so much light it made her blind, and then he dropped the veil and pointed to a dusty road and said that is the road you must travel to reach the light—that road was her destiny and also would take her to her destiny. Part of my work as a Sufi teacher, and the work that I have been trained to do, is that when somebody comes to this path, to recognize the destiny of their soul, the highest potential of the soul, and to help them to have the circumstances to enable that to be fulfilled.

These circumstances take different forms. Sometimes, not so often, one points to a certain shift in outer life circumstances. A couple of years ago I said to somebody I met in London, “you really need to come here to America and be with us, if you want to live out your soul’s destiny, it just won’t work for you in England.” But normally it is an inner connection that is given to them—a connection from heart to heart through which a certain love can be given to the wayfarer because we work with love to transform them and give them the energy to follow the path. This connection in the Naqshbandi tradition is called rabita. Then mostly I leave them alone, but occasionally I have to point them in a certain direction, to realign them. A bit like being a chiropractor, you do a realignment so that they have the possibility to live out their highest destiny. Sometimes this happens during life and sometimes this happens at the moment of death. There was a friend who passed away a few years ago, and I sat with her in the hospital two weeks before she passed, and we just there and sat there and I prayed with her and suddenly her eyes filled with light and she saw the light to which she was going and there was this great big smile on her face. Her whole face lit up and I thought, now I’ve done my work, now she is free to go on. She has fulfilled her spiritual destiny in this life. One can have a physical destiny, but spiritual destiny has to do with the spiritual evolution of the soul. So everybody has a destiny.

What was probably unusual for me is how little of my destiny was my own personal story. Looking back it is as if I stepped into much older story. It certainly wasn’t the story an English schoolboy. It wasn’t really even the story of the young man practicing Zen meditation. It was more the story that began when Yûsuf Hamâdanî travelled from Baghdad to Bukhara in the eleventh century, and that began again in a smaller way when Irina Tweedie met her teacher in Kanpur in 1961. Hers was the story of a Sufi path coming to the West. My destiny, and also the destiny of my wife, has been to live this story in order to make this path accessible in the West.

I remember two years before we moved to America, when Mrs. Tweedie told me I was going to be a teacher, I said “no, absolutely not.” I had no interest in being a spiritual teacher; none at all. I saw the life Mrs. Tweedie lived, in constant demand twenty-four hours a day, people always coming to her door, no personal life, no friends. It was not in the slightest bit appealing, but she implied that I didn’t really have a choice, and eventually I accepted. Then we got sent to America. It’s unbelievably beautiful here where we live, but I’m very English by nature, and it’s a very different culture. But we were asked to bring this path to America. I spent many years travelling around America, connecting with people who belong to this path and making this path accessible in America. Then a few years ago, I took it to Australia and we now have a community in Australia. A number of years ago somebody came to me from Argentina, and I saw that their destiny was take this path back to South America.

P: That was a moment of direct seeing?

LVL: I’ve been trained to work with souls. There’s a book of the soul and you’re allowed to read this book because there’s no point in taking somebody into this path who doesn’t belong on this path—who maybe belongs to another Sufi tradition where, for example, music is what helps their soul to evolve. Here we work with silence and not every soul is attuned to silence. So I have been given the gift of being able to see the destiny of those people who come, who are serious, so that I can guide them. I saw that the destiny of the woman from Argentina was to take this path to South America, but I knew she had to wait a long time. She had to be trained to do this work. Most of it is done in silence, inwardly, and it took many years; now we have groups in Argentina and Chile.

So there are these threads of destiny, and this really has to do with Mrs. Tweedie, who brought this path from India to the West. Her teacher said there was no point in his going to the West, he’d just be another Indian gentleman with a long beard. So he found a disciple whom he could train to bring his path to the West. She was old (she began teaching in her sixties until she retired in her late eighties) and she was passionate and she was an extraordinary person. She was asked by her teacher to write a book about her training, Daughter of Fire, she was the first woman to be trained in this Sufi path.

When you wrote and asked to interview me about destiny, I thought that was interesting because I’d never really spoken about destiny. Also this is a particular moment in my destiny, because my life’s work since I met my teacher was to establish this path in the West. She brought it to the West, and when I first came to her group there were just ten of us sitting in her little room in North London by the train tracks, meditating, having a cup of tea together, and slowly it grew, but she never established an organization. She left behind one amazing and unique book, a few interviews and some lectures in German. I was asked to establish it in the West. So I’ve written many books that try to explain the Sufi principles and practices and also given talks about this tradition to make it accessible to people in the West. We started a nonprofit organization and now it’s established. Three or four weeks ago, again I saw this book. I see it from time to time, every few years, the book of my life.

P: And it changes color?

LVL: Yes, and what is interesting is that it often has a leather cover because leather symbolizes the physical world, our body, and it means what has to be lived in this world. Some things have to be lived in this outer world, some just in prayer and meditation. In the book on a white page was written very clearly, “You have done everything you could do. It is over.” And that meant that this story I had been living since I was nineteen years old, of meditating and going deep within the heart and then bringing out the teachings of this path and taking the path to America as well as in Europe, has been completed. I’m not allowed to teach in India, I am only allowed to teach in Europe, in America, and Australia. It can’t be more, it can’t be less, and I have trained my son to continue this work. When he was born I had a dream from my teacher that told me this was going to be his destiny, and he started meditating when he was six years old. He was trained since he was fifteen years old, and in the last year he has begun to take on this work so it will continue.

So this path is now established. That story in my life has been told. I have lived it. It took more out of me than I would have believed possible. When you have these forces that make you live a destiny that isn’t just your destiny, it is incredibly demanding because you’re always living on the edge, you’re always being pushed and pushed by these forces. You never get a chance to rest. I haven’t had a year off in forty years. Fate, as you said, is something that happens to you; destiny is more this current of energy that takes you on a journey, and this story in my life is apparently over. There are still people here, they come and this is why I wanted to bring you to sit here with people because this is how it was in the beginning for me when I came to Mrs. Tweedie’s. There were people sitting together—what is called in India satsang, sitting in the presence of the teacher. My destiny, my story, has been played out in this traditional Naqshbandi way of sitting together. What happens now? I don’t know.

P: I personally would have a moment of uh-oh. You have experienced these powerful forces, this force of destiny. Yet you’ve written about the illusory nature of journey. And you powerfully convey that it’s nothing personal to be picked.

LVL: I often think they, the masters of the path, went through a list and that person’s busy, that person’s busy, that person’s busy—well there’s this guy, you know?

P: He’ll do.

LVL: Yes, he’ll do. Do I think somebody else could have done it better? Yes. I’m a very introverted person. I’m happiest left on my own. Yet I sit with groups of people. Why me? I don’t know.

P: This segues into the underlying question: why do we have these particular “I’s”?

LVL: Irina Tweedie met the Dalai Lama twice: once when he was a young monk in India, and once in 1984, in Interlaken, Switzerland. Each time she was allowed to ask him a question and she asked him the same question twice. The question was, “In the deepest states of nirvana does anything remain?” The first time he said, “Well, I’m a young monk and I don’t know from experience, but from what I have read, yes, something remains.” Thirty years later, she asked him the same question and he said, “Yes, from my own experience, something remains. Otherwise there would be no purpose to the whole human experience.” That really is the nub of my personal journey in the midst of this other story. As I said, what always attracted me from the very beginning were deep states of meditation—that you can go into meditation and you can go beyond the mind and you can go beyond the ego and beyond the body and you can get absorbed in extraordinary other dimensions. This is part of our mystical heritage, Thomas Merton writes about it very beautifully, “desert and void.” The Sufis write about being lost in love, absorbed in love, but as you said something comes back. I think there is also a story about what comes back. What is the real nature of the human being if you take away everything? Yes, one can say the true nature of the human being is this divine spark but it’s also a very human spark.

I wrote two autobiographical books. The first one, The Face Before I was Born, tells the story of what happened since I was sixteen years old—a story of spiritual transformation. The recent one, Fragments of a Love Story, was more about what was it is that remains. What is this very human element? And I haven’t understood it yet. Maybe this is something I will never really come to understand. I don’t know. What is the real nature of the human being that is divine and yet human? We come from a patriarchal era and most of the mystical traditions are about being lost in bliss or ecstasy, about absorption, about oneness with God, about being taken into the infinite ocean, of the drop returning to the ocean.

But I always return to the idea of relationship which I feel belongs to the feminine. In our very human essence there is a relationship to God, to each other and to the Earth and all of creation.

Essentially this is not a relationship of ego, nor a relationship of will, but a relationship of love. There is something deeply, deeply human in such a relationship that is to me the very essence of the human story. You can sense it when two people really meet. There is something in that moment which is deeply human—it is the heart’s story not just the ego’s story. The ego has wonderful stories and terrible stories and you can see them in the world around us. But the real human story is, I think, something that we need to rediscover. What is it that remains in the deepest states of meditation, of nirvana, as well as in daily life? What is the essence of our human experience? I hope we rediscover this as we move out of the patriarchal era into an era that is more to do with relationship, because it is vital that we make a relationship with the Earth again—and a relationship with what is sacred within creation again. It will contain this very human quality that is divine, yes, but not just a radiant light that blinds you, not just a fire that consumes you, not just a love that absorbs you. Our story and the Earth’s story are so important at this time—we have a shared destiny.

P: We have consent to open to one another and to life.

LVL: We have to say yes. That’s why I love Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in James Joyce, Ulysses, where she says, “Yes, yes, YES.” And I often think when one comes to die, one should be able to say two things: I have lived and I have loved—that one has said yes. Unfortunately for a long time I had a habit as an old monk of saying no, of turning away from life, because that was the monastic tradition—that one turns away from the outer and goes to the inner. But each time I’ve lived this to its logical conclusion I have been sent back, but sometimes I was not very happy about being sent back! I’ve tried diligently to say yes but maybe that is where free will comes in. There is the free will of the ego, in which you can say yes to this or no to that and that’s what we normally think of as free will. But there is also free will of the higher Self. I will give you an example. When I was twenty-three years old, I had some very powerful experiences and one of them was that I was standing outside in a garden and suddenly I was taken right out the top of my head far away. I was told very clearly, “you are free now, you can go,” and I said, “No, I am a Sufi. I am here to be in service,” and I came right back. And that’s in a way when another whole story in my life began, which had to with learning to be of service.

As far as I understand, my soul also has free will. It’s different from the free will of the ego. I suppose it is more the bodhisattva motif—that I was taken to the light and then I agreed to come back. It has to be the free will of the Self, to turn back into the world. Your life is never the same because once you’ve seen that light, once you’ve known the other world, it doesn’t make life here easier. Yes, you have access to grace. Yes, you have access to love. You have access to states in meditation that most could only imagine. You know there is a world of light and yet you have to come back into this world, which doesn’t really make so much sense after that. Why do people do what they do, when they could just take one step and be attuned to their soul, or experience the world of light? Yet most people are veiled from it. It’s very strange. I don’t really understand it. Again, there must be a very deep mystery to being a human being.

Every soul has a destiny to discover because otherwise why would the soul come into existence? My friend’s mother had a taste of the mystery of being human by being a mother of five children. I think it is within the destiny of every soul to uncover a little bit of the mystery of what it really means to be a human being. I often return to the first experience I had when I was sixteen years old. There were two aspects of it. One was that I woke up in meditation and discovered what the Buddhist’s call the void, planes of nonexistence, incredibly beautiful, so free. But at my boarding school there was a garden, which was beside the river Thames in England. Nobody went there very much. But it was a very beautiful garden full of flowers and there was a stream, and the silence, the beauty, the colors, the birds, the butterflies, touched me very deeply. As much as I was being taken into the inner world, there was this other thread of my destiny that pulled me into the created world.

They say in the Naqshbandi tradition, the end is present at the beginning—that when you first step upon the path it contains the seeds of the whole journey. In the last ten years or so I have been drawn very much into what I call spiritual ecology—the nature of our spiritual relationship to the Earth at this time. The Earth is going through a time of crisis. People politely call it climate change. But what I’ve come to understand is that it’s not just a physical crisis, it’s a spiritual crisis. The ancients always understood that the Earth is a living spiritual being. Just as we have a soul, the Earth has a soul, what they called the anima mundi. This is a time of possible transformation of the Earth, and also a time of crisis for the Earth. The Earth is calling to us and needs our attention. This is a moment in the destiny of the Earth.

P: You speak of voluntarily returning to the Earth, as bodhisattvas return. This flows from the particularly human feeling of compassion, which I’ve heard Buddhists define as the quivering of the heart.

LVL: That’s beautiful—the quivering of the heart.

Recently I have felt more and more what I call “the cry of the Earth.” It has evoked a deep love for the Earth, this Earth that has given me life, that has been so generous with me. Thich Nhat Hanh says, “we have to fall in love with the Earth,” and Joanna Macy, whom I deeply admire, calls it “The Work that Reconnects.” It is our love for the Earth that will help heal the Earth. We are at a pivotal moment in the destiny of the Earth and our story is the Earth’s story. Our destiny is also the Earth’s destiny. I don’t know how much the destiny of the Earth is tied up with the free will of human beings. Fifteen years ago, I was given a whole series of visions about the Earth: about the possible future of the Earth, about the Earth waking up, and about the heart of the world starting to sing—that was for me the most precious of all of the visions I was given. Suddenly, I heard the song of the soul of the world, the song of all creation. I wrote about it in my book Darkening of the Light.

It was unbelievably beautiful—the world as a magical being, as it is to meant be, waking up and transforming everything, coming alive again in a way that we can’t imagine because for so long we have forgotten it. And then I watched the dust settle over it. I watched the light starting to go out. For me this has also been played out on a world stage, symbolized by two climate change conferences. The first one was the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992. The world came together, all the politicians and environmentalists, to really look at the environmental future of the Earth as one human body. This is very important because the destiny of the Earth has to be about oneness, about unity. When they talked about sustainability in Rio, they meant the sustainability of the Earth as a whole. But when they came together in Copenhagen in 2009, they used the term sustainability to refer to whether the Earth could sustain our present, energy-intensive way of life.

I wonder how much free will human beings have in the spiritual destiny of the Earth. I wonder whether those of us who are called to say yes to working with the Earth can balance the very powerful forces of exploitation—forces of consumerism, multinational forces, forces of greed. We also have to say no quite categorically, that sustainability is not about supporting our consumer-driven culture, but about all of creation. When I wrote Spiritual Ecology: The Cry of the Earth, I called it that because the Earth is crying and some of us have heard the cry. In his encyclical, Pope Francis talks about the cry of the Earth and the cry of the poor because they go together. What is the destiny of the Earth and what is our relationship to it? Can the Earth as a living being throw off this dark magic of consumerism that is destroying it?

P: Enough of this greed and manic consumerism! Has our collective spiritual destiny changed? Are we shifting from an emphasis on the individual path to our collective path?

LVL: I wish I could say yes. I come from a tradition from India, and part of my work was to rearticulate some of the ancient teachings in a way that we can understand in the West today. One of the very primary Sufi teachings is, “take one step away from yourself and behold the path.” But when I came to America, I sadly found something very strange had taken place: a certain foundational spiritual teaching had not been included. The fact that it’s not about you—or the fact that spiritual life necessitates service—had been not dismissed but sidelined in favor of what I now understand to be the self-development movement or the self-empowerment movement. In a strange way the American focus on the individual has rewritten the sacred texts so that what matters is your own individual spiritual progress or awakening, rather than understanding that it is not about you—the Self that awakens in you belongs to a greater wholeness, you are a part of a greater wholeness—the individual atman is the universal atman. And you are in service to that wholeness. In the words of the great Sufi Ibn ‘Arabî, “Union is the very secret of servanthood.”

So in my understanding, a lot of the spiritual light that was given to the West by these great traditions was coopted very subtly by the ego and its illusory sense of an individual self. I think one of the reasons has to do with money. Spirituality has been taken into the marketplace in America and is sold. In the Sufi path I grew up with, money was never charged; money was not involved at all. But here spirituality has become a commodity. And if you sell something to somebody they want to get something out of it. If I say: do this meditation, do these practices, listen to these tapes, and you’re going to feel empowered, you’re going to feel better, you’re going to have more insight, you are going to have a more meaningful life—you will hand over the dollars. But if I say to somebody: do this practice and you’re going to learn how to be of service, you’re going to learn how to give yourself away more easily, you’re going to become nothing—this is not so popular or inviting.

P: They won’t sign up for that.

LVL: They won’t sign up! So you have a business organization, which is what a lot of spirituality in America has become.

P: And this model is exported to Europe and the UK.

LVL: Right, and probably back to the East. So this essential ingredient of spirituality has been overlooked. There is a Tibetan Buddhist practice in which you take upon yourself the darkness of the world. There are monks and nuns who pray for the well-being of the world, and that is not a popular practice. So this bigger dimension of spirituality, which I think is vital for the spiritual transformation of the planet, is often missing. That’s why I very much admire the work of people like Thich Nhat Hanh and the engaged Buddhists who say, “no, what matters is the planet.” For my parents generation the greatest event that called them was the Second World War. My father was away for five years at sea on a minesweeper and my mother drove ambulances in the Blitz. What calls us now is this ecological crisis, and it is a cry from the depths of the Earth. I think spiritual life, real spiritual life, has to involve service.

P: I recently asked a young theoretical physicist what he learned about life from his advanced studies. He said “in the light of vastness of the universe, no one is special.” He has no patience for people who cling to the illusion that they are special. So I wondered if you could speak to that.

LVL: Having experienced the vastness, it has actually taught me the opposite—the uniqueness of everything. I have a little bird feeder out in the garden and I love to sit and watch the ordinary house sparrows come. They eat the seeds so quickly, every two or three days I have to fill it up. They are like this unique fluttering of light that is the other side of the coin of the vastness. This is why I said that to me there is a very human story. My teacher said the Great Artist never paints the same thing twice so everything is unique, everything is special because it is a creation of the Great Artist. But for me it has come more from experiences, because I have been to the vastness, I know the vastness, I go there in meditation and yes, it is completely intoxicating. What I have found is that in the end it does not diminish the ordinary human experience, but it reveals a secret within it. There is a Sufi saying, “Man is My secret and I am his secret and this is the Secret of secrets” and it is this, what I call the bond of love between the Creator and the creation.

Understanding this bond of love has been one of the central themes of my life—that there is this extraordinary relationship of love between God and creation, between the vast emptiness out of which all creation comes and the created world. It’s an extraordinary relationship because it’s a relationship of love—lover and Beloved. Part of the privilege, if you like, of my mystical journey has been to experience this love that underlies everything, that supports everything, that nourishes everything, that speaks to everything and that knows the name of everything.

I understand that theoretically vastness can make us seem completely insignificant, but not if you experience the vastness with the heart, knowing the bond of love that unites all of creation.

P: You discover that God loves the piece of dust.

LVL: Yes. And if you ask me what is free will, I understand it as the freedom to say yes to our destiny. It is the freedom or choice to say fully yes. Many people say only partly yes, a conditional yes on their own terms. That is their freedom and that is their right. But the Sufis say it is the consent that draws down the grace, which I think is the same as what you say about consent. Then something very mysterious happens as life opens and speaks to us and life reveals its secret, which is different for each of us because, as you said, we each have our destiny. Every human being, but not just every human being, everything in creation, every rose has its destiny, every hummingbird has its destiny, because they all sing the name of God.

P: I’m thinking of the forces that keep oil companies and other companies doing what they are doing, no matter the cost to the planet. Do you believe there’s a force of conscious evil?

LVL: Yes

P: This rarely gets articulated. People act as though it is a matter of ignorance.

LVL: Well, that is a difficult subject. For most people darkness is ignorance and they make mistakes because they don’t know better. They think their lives will be fulfilled by going to the mall or buying a bigger TV—if they knew better, if they knew what would really fulfill them, give meaning to their lives, they wouldn’t be so caught—but they are ignorant. In the Sufi tradition this is the veiling of the truth; the truth is veiled. But I have been drawn to look a little bit more closely, to go under the surface a little bit, particularly in relationship to the present situation in the world, and there are forces at work that do not want humanity to change, that take our lifeblood, that take the light of human beings, turning dreams into desires, turning hope into greed. And we have no understanding in our culture of the inner worlds.

We live in a strange culture because we say all that exists is the outer, physical world. We’re the only culture that’s ever said that, and as a result we don’t have any understanding of the forces within creation. As well as beneficial forces there are forces of darkness in the inner worlds—yet people say it’s all the fault of governments or the multinationals. And yes, those big corporations exploit and pollute, ravage the Earth for their own greed, but behind and within them there are darker forces. Evil is a very big word. I just like to say there are forces of power and greed, and then even darker forces at play in our world today. These turn young people into terrorists who blow themselves up in the marketplace or in the mosque and misuse the name of God.

P: It seems to be a moment when it is necessary to take a stand in some way. Is it enough to have a personal destiny and a personal glimpse of reality?

LVL: From a mystical point of view what I have learned is that the first step is to recognize what is really happening. In Sufism we call that witnessing, being aware. I spoke with Joanna Macy about this. We need to feel it, and often there comes this feeling of grief at what is happening to our world. For me personally I feel a deep sadness at what I have witnessed both in the outer world, ecologically, but especially the desecration of the inner world caused by our forgetfulness of the sacred. But the sadness, the grief, can then take you to love, because if you feel deeply enough it takes you to your heart. I’m a great believer in doing small things with great love. I don’t actually believe in big organizations. Big organizations easily become very subtly corrupted. I believe in this link of love and I believe in the power of love. I believe, yes, you take a stand but you take a stand for love, you take a stand for care, you take a stand for compassion. Some people are called to be activists—if you are called to be an activist, follow that calling, but know that it very easily constellates into “us and them.” The next step has to be an evolution towards wholeness, unity. We’re all here together. The original instructions of the Native American teachings is that we have to get along together. But it is very important to witness what is happening, to recognize how we’ve allowed these seeds of darkness to take root.

P: The Latin and Greek root of “martyr” means to witness. Is it possible that this is the human position, to witness and to burn? Not outwardly but inwardly. We have to see and hold the grief and love and burn.

LVL: I think that it does burn you if you hold it, yes. I had a very personal experience in this because I started to see too much, I saw too much of what was really going on. I wrote a book, which I knew wouldn’t be very popular, Darkening of the Light, because I couldn’t hold it anymore on my own and writing alleviated it for a while. I don’t know the answer. I actually don’t know what will happen to the world at this time. I think we have to take responsibility. Sadly we are very naïve, particularly in America. We don’t really understand what is going on and I don’t quite know why. As a mystic, I believe in grace, I believe in love, I believe in Truth. I do see the possibility of a global transformation and I’ve been shown what life could be like if we really live the future that is being offered. But then I see these forces against this. I call it dark magic—how even consumerism is a very dark magic. Why would we destroy the planet for cheap goods from China? It doesn’t make sense.

Will it really change? I don’t know. I understand a little bit of my own destiny. I understand a little of working with the destiny of individual human beings. But the destiny of the planet and our relationship to it? Sadly, I sense that collectively humanity has made a decision: they want materialism, they want their energy-intensive culture. They can call it “green economy” and say they’re doing wind farms or solar panels, but it’s still what one might call the old story, a story that doesn’t make sense because materialism doesn’t nourish your soul.

What will it take to give birth collectively to a new story, to a story based on reclaiming what is sacred, turning to what is sacred? Parabola tells these stories over and over again. If you go back the forty years it has been published and open any volume, it has a story of the sacred told in one culture or another. It is really the deepest story of humanity—the story of our relationship to the sacred within creation. Yes, there is a disembodied God and one can reach that in meditation. But there is also an embodied God that is the sacred within creation. We walk upon it and we eat it and we breath it. Every breath is sacred, that’s why so many spiritual practices are based upon breath. Food is sacred. I remember the very first meal Mrs. Tweedie cooked for me; I didn’t believe you could taste love.

P: What did she cook?

LVL: She cooked some Indian patties with some chutney. She liked cooking Indian food because she loved her time in India, and there was love in the food. These are the real stories of humanity—simple, ordinary. You don’t need ten-thousand channels on the TV or high tech to tell a story of friends meeting, of a kiss, a handshake, a hug, of seeing a rose bloom, of responding to the cry of a child.

P: Is this our common human destiny, to find the sacred in the ordinary?

LVL: I think this is the greatest need of the time. When Oprah asked me if I had one thing to say, I said, “Remember that the world belongs to God, the world is sacred.” That is what we have lost. I don’t know why we lost it. I don’t know where we lost the thread of that story—how we lost the real meaning of life, because the real meaning of life is not to go shopping. The real meaning of life is to care for your children, to have a meal with your friends and family, to pray together, to see a sunrise, to love somebody, and, if you are drawn to it, to love God.

P: Following on your mention of Oprah, do you have anything that you would like to share with the Parabola readers about free will or destiny?

LVL: I think we each have a destiny and our free will is whether we have the courage and the commitment and the ‘yes’ to follow that destiny. Some people’s destiny will take them to places in the outer world. Some people’s destiny will take them to really meeting their neighbor. And some people’s destiny may take them into the inner worlds, on the journey towards Truth.

P: People are going to wonder: how do I hear the call of destiny? There’s a tendency in us to always reach outward to the teacher or to the Internet. How do we know when destiny is calling?

LVL: I think we have to reclaim the wisdom of the feminine: to learn to listen, to learn to wait, to learn to be patient. There is saying in the Qur’an “We will show them Our signs on the horizons and within themselves.” And you learn to recognize the signs, you learn to watch, to listen. What is life? I can only talk as a Sufi and for the Sufi life is a love affair. What you hopefully learn when you’re in love with another human being is to be attentive to the needs of your beloved—to listen, to watch, to be present in that moment of love. I think life is also a love affair because the world is created out of love, and it’s a question of whether one has the patience, the openness to learn to be present in life, to learn to have an open heart, to allow life to tell you its story.

You see our destiny and the destiny of the Earth are bound together in ways we don’t understand and if you allow life to speak to you, if you learn to listen to life, it’s not about what “I” want from life. Sadly in America they’ve misunderstood following your dream or living your dream or destiny—it’s become like a product or lifestyle. We are part of life’s dream, we are part of life’s destiny. We belong to this living oneness, this beautiful suffering wholeness. We need to find this thread of the real story of our life—not the story that we see on the television or the news, not even the story our parents tell us—but the real story of our life; you can follow that. I was taken by a story and turned inside out and was taken to other realities, to other continents, and was consumed by a story. For most people probably it’s not so dramatic, but in a way it’s the same story. It is life’s story, it is the Beloved’s story—it is the one story. But it’s whether we are prepared to say yes to it. Yes?

P: Yes. Thank you.♦

A shortened version of our interview with Sufi master Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee appears in the printed version of Parabola, Volume 40 No. 4, Winter 2015-2016: Free Will and Destiny.