In my mid-thirties I found myself in Dante’s dark wood, where my way was entirely lost. My marriage was falling apart. My primary mentor, Reynolds Price, seemed to be dying of a weird spinal cancer that was slowly paralyzing him. My visits to him brought up visits I’d paid to my father in the hospital when I was fifteen and sixteen, just before he died of leukemia. There was a lot of unfelt grief there (I hadn’t felt it because I was afraid of it), and I was suffering, sometimes doubled over in pain after I visited Reynolds. Very reluctantly one day, I said to a close woman friend that I thought I needed some help with all this. Maybe I needed to see someone.

“I think that’s a good idea,” she said.

The therapist I began to see was a huge help, and we focused on a host of issues. On another day, when I was talking to that same woman—she was a fellow writer, and we had lunch every couple of weeks—she said, after some remark I’d made, “You have a lot of anger about religion.” I was startled by that, not so much that she said it but that she knew it. How did she have such information? I brought it up with my therapist, and he said, yes, you do have a lot of anger about religion? How did he know? What the hell was going on here?

“I don’t know why that would be,” I said.

“I do,” he said.

He told me that he had five clients who had the same anger, and all of them had lost parents as adolescents. They’d been questioning religion anyway, then this thing happened that shattered their lives, and people offered idiotic religious platitudes to comfort them. “It was God’s will. He needed another angel in heaven.”

I’d definitely had that experience, but I had also put a lot of effort in my twenties trying to find a religion and a faith community that made sense to me. I went through all kinds of contortions. People kept telling me—this was the essential Christian message—that if I could just believe something or other, I would find peace, but I couldn’t believe that thing. I didn’t even understand it. I wasn’t sure whether religion wasn’t right for me or I wasn’t right for religion. It seemed like a dead heat. But something was wrong.

I could admit I was angry. I couldn’t tell whether I was angry at religion or at myself.

It wasn’t true, however, that I didn’t believe anything. I had an intuitive understanding about God and the nature of reality, but it didn’t resemble anyone else’s, or at least I couldn’t find it in any religion. But I wrote it in my notebook and decided that was my religion. One congregant. Me. It seemed like a lonely fate. But that’s the way things looked.

Then I did something quite uncharacteristic. I’d spent my life wanting to be a writer of literary fiction, gave all my time to that effort, avoiding various fads of my generation. Siddhartha, Lord of the Rings, Ken Kesey (I’ve read them all since). In particular, I hadn’t dipped into Eastern religion because an influential professor, a New Testament scholar, told me Western people couldn’t authentically practice that. They had to stay within their own tradition.

My wife, whom I’d met back in college, hadn’t felt that way, and owned a number of those books. In my utter despair, I picked up one that I’d never even looked at, and that expressed everything I’d avoided while all my friends followed fads and I read the great literature of the world. It still had her name in it. The Way of Zen.

In that book I found these words:

“There was something vague before heaven and earth arose. How calm! How void! It stands alone, unchanging; it acts everywhere, untiring. It may be considered the mother of everything under heaven. I do not know its name, but call it by the word Tao.”

That was so much like what I’d just written in my notebook that I couldn’t believe it. I read on:

The Tao is something blurred and indistinct.

How indistinct! How blurred!

Yet within it are images.

How blurred! How indistinct!

Yet within it there are things.

How dim! How confused!

Yet within it there is mental power.

Because this power is most true,

Within it there is confidence.

It was incredible that someone else saw things that way. But it wasn’t some one. It was a whole spiritual tradition, which had been around for centuries.

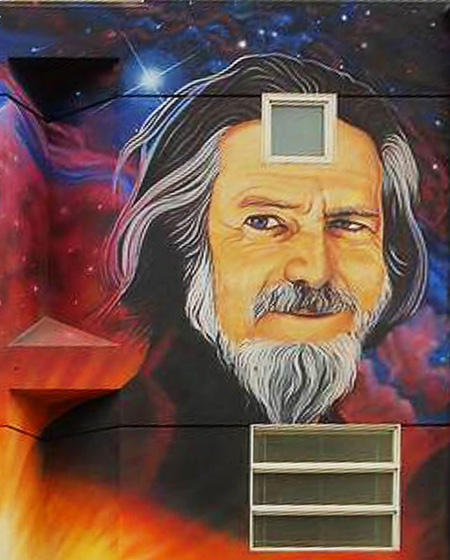

Alan Watts, it seemed, was a person just like me (he wasn’t, actually, but it seemed that way on the surface). He wasn’t some airy fairy hippie who had a dreamy look in his eyes and couldn’t get specific about anything. He was a rational logical Westerner with an incredible ability to explain abstract things in a straightforward way, and was an excellent writer. I loved reading his sentences. His view of religion was larger than anything I’d encountered up until then. It had nothing to do with believing. It was more like a sense of wonder at the mystery of things. And there was something lighthearted about the whole endeavor. It wasn’t life or death—actually, it was, but he still managed to be lighthearted—but more like something to play with, or speculate about.

Actually, The Way of Zen was slightly straitlaced for Watts. It was his breakthrough book, and his work after that took on a free-flowing quality that the earlier writing didn’t have. Psychotherapy East and West spoke about the way that the methods of therapy—which I was going through right then—resembled those of Eastern religion, and might lead to the same kind of realization. Nature, Man, and Woman talked about the way sexuality might be a part of the spiritual quest, and took for granted the important place that sex had in human existence. The Wisdom of Insecurity (actually earlier than The Way of Zen) spoke of the way that doubt and not knowing were an important part of the religious quest, not things that needed to be wiped out by blind faith in some creed.

The thing that was most helpful about his vision was its sheer freedom, the way it opened things up rather than closing them down. What a relief.

I’d seen photos of Watts in a clerical collar, imagined he was an Anglican minister who had begun in the Christian religion and gradually opened to Eastern thought. Actually, he began as a Buddhist, growing interested as a schoolboy and joining the Buddhist Society when he was nineteen. He wasn’t university educated, but was a self-starting autodidact who absorbed an enormous reading list he created on his own. He joined the Christian clergy after his first marriage failed, in an effort to make a living. As his books began to sell he abandoned the clergy for a wild bohemian lifestyle, and became an icon of the swinging Sixties.

Zen in Watts’s account seemed an ancient practice that expressed deep wisdom. The one thing Watts didn’t mention was that, not only were these religions still practiced in the modern world, they were making their way to the West. It was seven or eight years before I would practice Zen and thereby understand it in a deeper way. Alan Watts served the purpose of the drug experiences of many of my contemporaries: he opened me to possibilities I had never considered.

Eventually I read almost all his books, also the Monica Furlong biography and Watts’s own memoir, In My Own Way (the only literary memoir I know that doesn’t have a nasty thing to say about anyone. It has a generosity of spirit that I find remarkable). I came to understand that, in a lot of ways, Watts was more Taoist than Buddhist; a late work like Tao: The Watercourse Way expresses his spirit more than other books. I eventually profiled him for a magazine and included a chapter about him in one of my books. I could see his limitations: his Buddhist focus was more on Rinzai Zen than Soto, and he made enlightenment sound like some mental gimmick, rather than a profound change that might occur after long training; he was always a bit of a rascal, never much of a husband or father (as he admitted himself); especially as he got older, he drank too much, probably way too much. He wasn’t a dedicated practitioner of Zen or any other religion; he was, however, a brilliant scholar and writer with an amazing facility for explaining things. His wild lifestyle may have led to his early death, at the age of fifty-eight, in 1973. That seemed like a shame. We could have used his wisdom for years to come.

But he is a man who led countless Westerners to Buddhism and a whole Eastern way of thought. He opened up the world for me at a moment when I was bewildered and full of despair. He led me to a religious practice that has been the most important discovery of my life. For all that I owe him an immense debt of gratitude. ◆

David Guy is the author of The Autobiography of My Body and Jake Fades. His sixth novel, Hank Heals, will be published by Monkfish Books in the fall. www.davidguy.org.