Parabola reached out recently, via a Zoom link, to Raphael Shuchat at his home in Israel. We had met him with his family at a vacation spot in upstate New York in summer 2021, not far from his original home in Montreal, and we knew within minutes that we wanted to introduce him to Parabola’s readers. Rafi, as he is called, is a university teacher, a scholar, and a good citizen of his adoptive country Israel, where he offers regular instruction to immigrants who wish to deepen their knowledge of Judaism. “Rabbi” and “Doctor” are equally accurate titles for the man. As a rabbi he is a warmly receptive teacher who wears his knowledge lightly. This is evident on his YouTube channel (simply type in his name). As a scholar he marshals immense erudition to illuminate themes in Jewish philosophy and mysticism. Kabbalah, more spoken of than understood, is his intellectual homeland. The following article begins with a compelling statement from the scholar, which we were surprised to receive when we broached the possibility of an interview—and then turns to conversation with the rabbi.

—Roger Lipsey and Kenneth Krushel

Opening reflection

from Rabbi Shuchat:

The Wonder of Creation

The first verse in Genesis is familiar to all: “In the beginning God created the Heavens and the earth.” From there, the story begins. “And the earth was chaos (tohu) and void (bohu).” Tohu is usually translated as chaos or without form, and bohu as void. However, Rashi, the classic eleventh-century commentator from France, says that tohu comes from the Hebrew taha, which means to be astonished. An observer would have been astonished at how empty everything was. The Bible begins with amazement and astonishment. The ultimate wonder is the act of Creation, the moment of genesis.

An ancient midrash (rabbinic bible commentary) from around the seventh century, called The Letters of Rabbi Akiva, describes the creation of the universe by the Hebrew alphabet. It is a lovely philosophical story. All of the letters gathered before the Holy One, blessed be He, and asked God to create the universe though them as His working material. First tav spoke up (the twenty-second letter), and then shin (the twenty-first). They were dismissed because they began words which were unfitting. Then bet spoke up, and God said: baruch habah (Blessed is he who enters), since bet is the first letter of the word “blessing” (brachah). Therefore God created the world starting with the letter bet, beresheit—in the beginning. The midrash continues that aleph, the first letter, did not take its opportunity to present its argument and stood sheepishly aside, but God said: aleph, don’t be concerned. When I give the Decalogue to Israel at Sinai, I will begin with you. Anochi adoshem elokeikah—I am the Lord your God.

This mystical midrash is based on two assumptions: 1) The letters of the alphabet were used as information bits to create the universe, and 2) The order in which they are found in the Torah represents a code. The sixteenth-century Maharal of Prague, famous for the Golem legend attached to his name, explains that bet, being the number two in Hebrew numerology, represents the multiplicity of the natural world (day and night, light and darkness, male and female, good and bad, positive and negative). Whereas aleph, being one, represents unity. Aleph represents the source from which the universe arises. It is the ultimate object of amazement, the wonder itself.

A further teaching from ancient sources: aleph, in Hebrew ל ף, א , spelled backwards is “wonder” (pele), פלא. Pele or wonder is the cause of astonishment at the moment of Creation. The word pele or aleph, from the point of view of gematria (numerology of the Hebrew letters), encodes as 111. It is three ones: as a single digit, in tens and in hundreds. Here is a beautiful detail: the final 1 is hidden in aleph itself since aleph spells elef, which is 1000 in Hebrew. This is the fourth 1. Aleph is all the beginnings of the four upper worlds of the Kabbalah: Atzilut, Briah, Yetzira and Asiya (emanation, creation, formation, and action).

What is a wonder? What amazes us? We have already encountered the wonder of tohu in Genesis. There is another instance of wonder or amazement in Genesis: the amazement of Abraham’s servant, who went in search of a wife for Isaac. When he met Rebecca at the well, he was astonished that the very sign he had prayed for (Gen. 24,14) had materialized—she generously offered him certain courtesies, water for himself and for his camels.

In Exodus there is a third amazement: the falling of manna from heaven. The verse says: “And they said: what is it (man hu)? for they did not know what it was” (Ex. 16,15). The commentators have difficulty with the meaning of the words man hu. Rashi explains that it comes from the Hebrew root “to prepare” as in Jonah (2,1): “and God prepared (va’ye’man) a fish.” The people were astonished that prepared bread fell from the heavens. Onkelos, a learned Roman convert to Judaism in the first century of the Common Era, and Abraham Ibn Ezra (eleventh century, Spain) take a different view: they understand it as the Aramaic manna, meaning “from where?” Where did this come from? A third interpretation is associated with another famed commentator, Chizkuni (thirteenth century, France), who explains that “man” in Egyptian means “what.” Leaving Egypt behind but keeping something of its language, the people asked “man hu”—what is this?

These are three interpretations of an astonishing event: how, where, and what. In our search to understand the primordial astonishment of Creation itself, we can learn something from these interpretations. How: How did the universe present itself to us prepared so intelligently—the ecosystems and biological systems, the intelligence of animals and of man, and much more, infinitely more? Where: Where did it all come from? How did it arise? And what: What is it? What is matter? Is the Creation only material, or is there more than meets the eye? What is man? What is the meaning of our existence?

These questions address the inner dimension of the universe, which in the Kabbalah is referred to as the Wonder. The Book of Creation (Sefer Yetzira), an early mystical work, possibly of the late second temple period, begins by saying: “In thirty-two wondrous pathways of wisdom did the Everlasting One create the world.” The highest level is referred to as the Wonder since it is beyond wisdom. Just as for manna “they said: what is it? For they did not know what it was.” It is the level above “knowing.” In the kabbalistic Tree of Life, there are actually two levels above human reason. One is called Hokhma or wisdom, the level of intuitive thought and of faith. The other is Keter, the level of wonder.

Let’s look a little more closely, relying on yet another traditional transformation of words and meanings. We know that the Hebrew for manna is man hu, מן הוא. If you interchange the letters, it spells אמונה emunah, which means “faith.” Faith is the intermediate level between reason and the wonder of the Keter (crown), the topmost energy or intelligence in the Tree of Life.

There is a story. In the battle of the Israelites against Amalak, it is said that when Moses raised his hands the Israelites were victorious, but when he lowered his hands then Amalek prevailed—so his brother Aaron and companion Hur held his hands high. The verse continues: “And his hands were faithful (emunah) until morning” (Ex. 17,12).

Raising the hand above the head represents the level of faith. Faith points us toward wonder. The goal of wonder is to open our minds to realities beyond our limits. In science, wonder creates original hypotheses, the source of all new discoveries. In personal life, wonder opens to possibilities of new spiritual growth. All human beings can find wonder within them. There is a blessing in the morning prayers: Blessed art thou, O lord Our God, healer of all flesh and master of wonders.

Rabbi Shuchat: We consider the Torah wondrous because it’s the word of God. Meaning there is something about it which lends itself to challenge us and make us greater than ourselves. If you remember, Abraham Joshua Heschel [1907-1972] said that the Bible starts with God looking for man. Even though people go to the Bible in search of God, in the Bible God is searching for man.

Parabola: The direction that Heschel takes in writing of wonder is not toward intellect only but toward state—the overall state of the human being. Is it my responsibility as an individual to free myself of trivia, of nonsense, distractions, preoccupations, in order to perceive God’s world in all its wonder? Heschel spoke of an intimate duty to come again to the state where we perceive the wonder that is always there. He spoke of “radical amazement.”

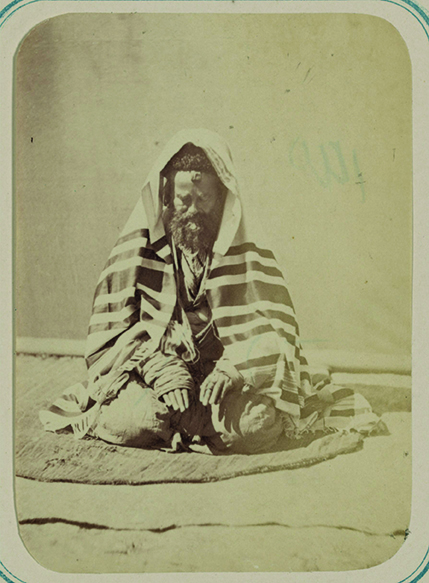

RS: Heschel felt that American society was losing the spiritual experience of religion. All too often people have an institutionalized notion of religion, and he was trying to teach a return to spirituality. Even in his book The Earth is the Lord’s, which evokes the shtetl Jews of Eastern Europe, he sets out to convey the experience of Jewish life, not just knowledge of Jewish life.

“Religion declined,” he wrote, “not because it was refuted but because it became irrelevant, dull, oppressive, insipid. When faith is completely replaced by creed, and worship by discipline and love by habit; when the crisis of today is ignored because of the splendor of the past; when faith becomes an heirloom rather than a living fountain; when religion speaks only in the name of authority rather than the voice of compassion, its message becomes meaningless.”

It comes back to the basic concept of belief in God. For a Jew, belief in God is not belief that, it’s belief in. It’s not scientific knowledge. If you talk with somebody on the street and give them twenty-two proofs of the existence of God, even if they agree with you, that won’t affect their lives. At the end of the day, belief in God is a relationship. It’s not simply to believe that God exists, it’s to believe in my relationship with God.

The level of wonder is a level within us. In Kabbalistic thinking, we believe that faith is a human ability. The Hebrew word for faith, as I mentioned earlier, is emunah. The root letters for emunah (aleph, mem, nun) also generate the word “amen,” meaning “I believe this”; the two words have the same root. That root also generates the word omanute, which means art, and oman, which is an artisan, with the implication that faith is a human art form. Faith is something we can develop if we take it seriously. It’s within our abilities. As I said, it’s not to believe that…. It’s to learn to touch inwardly the threshold between the ability to know and the intuitive level of wisdom.

P: What is the place of prayer?

RS: In general, when we pray, we talk to God, and when we study the Bible, God talks to us. Even though we might not be prophets, we are descended from prophets. When we want to know what God said at Sinai, we read the Torah, the Five Books of Moses. Then we try to relate to that prophecy, as it was related to us by Moses.

When we talk to God, that is prayer. But, again, what is prayer? The Yiddish word for prayer is daven, and there’s actually a question about where the word daven comes from. Some people think it comes from the word divine. Others think it comes from the Hebrew d’avinu—from our father, meaning our father in heaven. In Hebrew, the word tefillah is the word used for prayer. However, the verb to pray is Le’hitpalel, which is in the reflexive. It’s as if we are praying through our inner selves, it’s a reflexive act. The word tefillah has two possible roots. The first root is le’falel, which means to hope, and to expect. When Jacob met Joseph’s two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, for the first time, he said, Joseph, I didn’t even expect to see you, and now God is showing me your children (Gen. 48,11). He uses the word Le’falel meaning to hope, to expect. When I pray, I hope and expect that God will answer me. But that is not the end of the matter. The second meaning of tefillah is from the word plili, which in biblical Hebrew means an inspection (See Ex. 21 ,22). This explains why the reflexive is used. When I’m standing before God, not only am I hoping for something, but I am inspecting myself. Am I deserving that God actually grant my request?

In the twentieth century, there was an outstanding rabbi in Jerusalem, named Jacob Moses Charlap (1882-1951). He asked, what is the point of prayer? Are we trying to change God’s mind? But if God is infinite and all-knowing, then it would be foolish to think that we can change his mind, because obviously he knows more about the future than we do. What then is the point of praying? An interesting philosophical question. Rabbi Charlap continues that prayer involves introspection. If we prepare ourselves and if we are able to change ourselves through prayer and come to a better state, then maybe we’re now worthy for what we weren’t worthy of an hour ago. The point of prayer is to bring us to that better place so that we are now worthy to receive what we were asking for yesterday and the day before.

So it is not God who changes His mind, it is we who change our place vis-à-vis God. Prayer is both hope and introspection at the same time. Prayer is the attempt to connect. We also ask for things because we are limited, we need to ask for things. But first and foremost, prayer is the attempt to connect with God and to create holy time in our lives.

Parabola: Abraham Heschel comments that one challenge of prayer is our inability to understand and express what is felt in a moment of mystery and wonder. He suggests that God is affected by this “lack,” by this struggle with openness, and just there God expresses his “Divine pathos,” his compassion for our shortcomings.

RS: We begin our blessings in Hebrew with the formula: Baruch ata adoshem elohenu Melech HaOlam asher—“Blessed are you O God, King of the Universe who….” We begin in second person (you) and switch to third person (King of the universe who). This summarizes the religious paradox. On the one hand we pray to God in second person, as if, He, She, It, is our personal friend, and then we switch to third person since we know that God is also transcendent and the creator of the universe and above our comprehension. Jewish tradition teaches us to connect to God on a personal level while reminding us that God is above human perception: “To whom can you compare me and equate says the Holy One” (Isaiah 40, 25) The Hassidic tradition states that even the most spiritual of human beings has to live in the consciousness of “In velt Oys velt,” which in Yiddish means in the world but consciously transcending the world. We are all corporeal human beings but through our minds we can transcend mundane reality to attempt to reach higher vistas. The desire to connect with God as in unio mystico is often met with frustration by the mystic; there is that steel wall that prevents us from breaking the confines of this world. But the desire to have God in our lives and emulate his ways of morality and justice is what imbues our lives with meaning and makes them that much more worth living. ◆

This conversation appears in our Spring 2022 issue, “Wonder”. Purchase the issue here.