“I

was looking right at the White House,” my father said. “Can you imagine being right there when you heard that?”

My father always remembered driving down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., when President Roosevelt came on the radio to declare the day before, December 7, 1941, “a date which will live in infamy.” People tend to remember exactly where they were and what they were doing when shocking news comes.

During that famous live broadcast, the President was not actually in the White House but in the nearby Capitol addressing a special joint session of Congress, asking for a declaration of war. The day before, the Empire of Japan had attacked U.S. military bases in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and declared war on the United States and Great Britain.

“I regret to tell you that very many American lives have been lost,” said the President, calling my father and everyone in America to arms.

I picture my father driving along Pennsylvania Avenue, his head full of thoughts and plans. Just months before, he had moved to Washington, D.C., uprooting his life in northern New York, breaking with his mother’s wishes in order to take a job working on the construction of the Pentagon. I imagine his excitement and anticipation, a young man from the rural North Country now living in a city preparing for war. The atmosphere everywhere was bustling and expectant. Everything was new. He would have been thinking about what he had to do, about difficulties and challenges large and small. And then F.D.R came on the radio, and my father’s private world of thought would have evaporated like mist.

“We’re in it now,” my mother’s father said at a dinner table in western Nebraska.

Moments of shock awaken us to

a truth that we rarely glimpse

in ordinary times: we are not separate and

autonomous creatures, in control

of a good portion of our lives.

My father, who was to meet and fall in love with my mother in the course of the war, shared that same observation, and so did most of America. The live broadcast, which lasted about six minutes, was heard by the vast majority of Americans, and most of those listening remembered it in the indelible way my father did, when suddenly everybody stopped “going about their business.” Everybody said or heard or thought to themselves: We’re in it now.

It was as if the President had yelled, “Fire!” The response was immediate and overwhelming. Within the hour, Congress voted to declare war on Japan. The anti-war and isolationist movement collapsed on the spot. The famous aviator Charles Lindberg, who had been a leading opponent of entry into World War II, declared: “Now [war] has come and we must meet it as united Americans…. Our country has been attacked by force of arms and by force of arms we must retaliate.”

Recruiting stations went on twenty-four-hour duty to deal with the flood of volunteers seeking to enlist to serve, including my father. On December 11, 1941, Germany declared war on the United States, and we answered with our own declaration. Everyone who was qualified (and many who were not) dropped everything and ran to be one more pair of hands on the bucket brigade.

Virginia Woolf called the special memories that come in the midst of shock “moments of being,” noting in her journals that she spent most of her waking hours with her head full of “cotton wool.” But sometimes shocks came that woke her up from this dreamy state, igniting the sense that we are all part of a larger pattern.

Moments of shock awaken us to a truth that we rarely glimpse in ordinary times: we are not separate and autonomous creatures, in control of a good portion of our lives. We are part of a greater living whole, inextricably connected to others and to the life around us. We are not as free as we think we are. We are subject to myriad conditions, but we are also capable of more than we think. We are living participants in a greater creation, vessels for greater energies and forces. We can choose what we serve.

“Between stimulus and response there is a space,” wrote Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl in Man’s Search for Meaning, chronicling his time in a Nazi concentration camp during the war. “In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

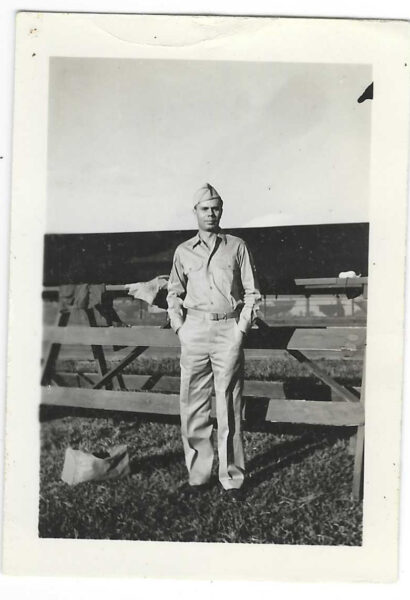

Some seventy-five million people died in World War II but remarkably few Americans, 405,399. Countless more people were wounded, orphaned, and displaced. My father was not among them. Like other American enlisted men, he went through three months of training and boarded a ship, willing to face whatever awaited him. The young men slept in hammocks on board and ate two meals a day, waiting and wondering what would come. It is astonishing to consider how little most of them knew when they were sent off to fight.

“They were always happy to have farm boys in a platoon because we knew how to do things,” my father told me. He had spent summers on his grandfather’s farm. “We knew how to chop wood and build fires and tell which way the wind was blowing.” At least a few of them knew how to shoot.

For security purposes, none of the soldiers were told where they were bound until they were well out to sea. My father’s ship headed towards the Pacific but he ended up in Panama, tasked with helping guard the Panama Canal against possible Japanese attack. Aside from sitting up all night in the jungle, guarding a plane that had crashed from wild animals and would-be scavengers, he didn’t see any action. He didn’t have to kill or face the horror of war.

“I was ready to go wherever they sent me,” he added when asked about his wartime experience, ever aware that he had been spared.

And yet he didn’t emerge from the war unscathed. Certain shocks take a long time to do their work slowly opening us, planting seeds. I once heard that the great martial artist Bruce Lee described certain blows that sent vibrations through the body that took years to take a person down. At the end of his life, my father told me that in the middle of the jungle in Panama, he received a seemingly small shock that sent out ripples that changed his view of life and what really matters.

He met another soldier whom he knew from home. It’s always startling to meet parts of our past when we are far away, although travel (and all the more so the dislocation of war) is renowned for providing fresh impressions of ourselves, heightened in new surroundings, exposing our assumptions and beliefs and ways, showing us how we are limited and how we might change.

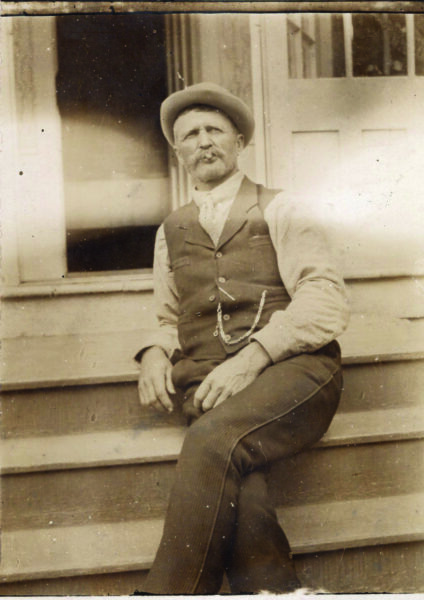

In the midst of reminiscing about the North Country, this other young man happened to mention to my father how my father’s own grandfather, the farmer with whom he spent summers, came to be called “One-Potato Cade.”

“Do you know why people called him that?” my father asked me. A few possibilities popped into my mind but I refused to venture a guess.

Cade’s hired man was invited to dinner, the story went. He was hungry from a long day working in the fields and after eating a potato, went to help himself to a second one. But old Cade batted his hand away.

“One potato’s enough for you,” my father intoned, imitating Cade’s proud, stern voice. “Can you imagine that?”

I couldn’t but my father looked at me with such sadness and disgust that I tried to soften the blow.

On the scale of sins someone can commit, I told him, denying a man a second potato has to rate pretty low. But my father shook his head.

“The real shame of it is that he grew potatoes.”

My great-grandfather had no shortage of potatoes. He raised pigs and potatoes, the things he truly liked to eat.

And the worst of it, according to my father, wasn’t just that outer act of meanness but the breaking of a deeper law: Any good farmer, any good person, my father told me, understands that kindness and generosity matter. The way you treat your neighbors and family, the way you treat everyone, matters. The hired man stood up from the table, collected his pitchfork, and left without looking back. Word got around.

There are seeds that need fire to sprout.

The lodgepole pine and other trees have cones

or fruits that are completely sealed with resin

and can open to release their seeds only after

the heat of a fire has melted the resin.

“I always remembered that story,” my father said. “I vowed that I wasn’t going to be like that.”

My father could see that I knew that he hadn’t always lived as if this was so.

There are seeds that need fire to sprout. The lodgepole pine and other trees have cones or fruits that are completely sealed with resin and can open to release their seeds only after the heat of a fire has melted the resin. Moments that spark shame or remorse can burn like cold fire. But if we can bear the suffering without fighting or freezing or fleeing or fixing, if we can open to the experience, examining it with curiosity and acceptance, new seeds of understanding can be planted. These seeds can take a long time to grow.

I picture my father as a young soldier guarding the crashed plane in the jungle, an experience he vividly remembered. He had to keep watch all night. I imagine him sitting up, aware of the sounds outside and the sensations he had to be feeling inside, aware of his heartbeat and his breathing. We innately return to the breath when we are alone in nature at night. We can’t help but be aware that we are held in a mysterious web of life, surrounded by other beings and energies. His thoughts would have been still, the stillness that comes with vigilance.

He would have been afraid of what might come out of the darkness of this unknown place, a heightened version of the fear that arises in all of us, that we are not enough to face what might come—that we are not brave enough or strong enough or smart enough, that we will be overwhelmed or devoured. And after that other young soldier told him that story, my father also had that extra twist of family shame that so many of us carry. Whether it is the secret knowledge of meanness or depression or addiction or abuse, we hold the shame close, hoping no one will discover what marks us as defective or lacking. But my father couldn’t leave his post, so I choose to picture him as a spiritual warrior, quietly facing his life. He would have daydreamed and planned to pass the time, but at other moments he would have contemplated One-Potato Cade, feeling pain and shame, but also catching a glimpse of his true possibilities. He was more than the stories he carried.

Shocks burn. They make impress-ions that literally scar us. Yet, as we learn to be curious about these impressions, examining them with an attention that doesn’t judge, we discover deeper feelings and truths. Slowly and gently, over a long time, we find that we are more than the stories we receive and tell ourselves. We discover that shame is the painful coating around tenderness and responsiveness. We remember that we have good hearts and minds, willing to open to give and receive.

I picture my great-grandfather Cade’s farm on Pillar Point, a peninsula of land jutting into Lake Ontario. I remember how long and hard the winters were in my childhood. The lake ice was so thick you could drive a car on it. The soil was so rocky that in the old days the farmers had horses draw sleds called stone boats through the fields to collect the stones, which were lined up and piled up to make boundary fences. When I see stone fences, I think of how hard their lives were, but also of how they contributed to their suffering with their grasping and fear.

I think of my father sitting in the jungle contemplating Cade and all his ancestors, settlers who treated the land like a dangerous wilderness to be subdued. I imagine my father questioning some of the values he was raised with, the self-sufficient rugged individual, thrifty and industrious, beholden to no one.

“It was our belief that the love of possessions was a weakness to be overcome,” wrote Charles Eastman, born Ohiyesa, the first Native American to be trained in Western medicine. He explained that in his tradition, children were taught to give away what they prized most, and not just to family and guests but to the poor and aged, those who could not return the gift.

I picture my father’s heart and his mind slowly opening like a closed fist, coming to understand this. This took longer than one night in the jungle. By the end of his time in the military, my father was an officer. But by the end of his life, he was a kind and generous man.

“We’re too old to cry over things,” both my parents said to me when their house was destroyed in a hurricane. “It’s relationships that matter. Love matters. Nothing else lasts.”

During a visit with him, months before he died, my father insisted on cooking a dinner for my sister and I, nothing fancy, meatloaf and baked potatoes (of course!). But he was well into his nineties, legally blind, and tethered to an oxygen tank due to emphysema and COPD, so he stopped to rest every fifteen minutes or so. I asked him if I could take over. He refused to let me.

“Do you want to know the secret of life?” my father asked. “You keep going for what you love, keep doing things for people you love. Just let things take as long as they take.”

At the end of my father’s funeral, because he was a military veteran, a rifle team of seven service members fired three volleys or rounds into the air. This was not, in spite of the twenty-one shots, an official 21-Gun Salute, which is reserved for heads of state. It was a military gun salute honoring an ordinary man who served.

According to military sources, the ritual of firing three volleys harkens back to ancient European wars, when fighting was halted to remove the dead and wounded from the field. The three rounds of shots signaled that the dead were cleared and properly cared for so the battle could resume.

Official military sources acknowledge that while the choice of seven rifles and three rounds may have biblical and mystical significance, the discharge of weapons, rendering them harmless, is universal. A military website points out that a North African tribe trailed the points of its spears on the ground to show that its warriors came in peace.

We have it in us to stop the battle. Some shocks teach us to drop into the depths of our hearts and minds, discovering that our true strength comes as we learn to open them rather than shutting down and armoring. Moment by moment, we learn what the first inhabitants of this land knew and what the oldest people know: We are part of life, not separate. Our own lives are brief and very limited, but we dwell in a great web of generosity. Consciously or unconsciously, we are constantly giving and receiving: breathing air, taking in food and impressions, offering our actions and words and presence. Life is constantly being offered to us while we are here, and we can’t help but respond in myriad ways. Opening to this truth, we can choose what we give. We can give love.

“What is life? It is the flash of a firefly in the night. It is the breath of a buffalo in the winter time. It is the little shadow which runs across the grass and loses itself in the sunset.”

—Crowfoot, Blackfoot warrior and orator

Love doesn’t just sit there, like a stone, it has to be made, like bread; remade all the time, made new.

—Ursula K. La Guin

The moment when, after many years

Of hard work and a long voyage

You stand at the centre of your room,

House, half acre, square mile, island,

country,

Knowing at last how you got there.

And say, I own this,

Is the same moment when the trees

unloose

Their soft arms from around you,

The birds take back their language,

The cliffs fissure and collapse

The air moves back from you like a wave

And you can’t breathe.

No, they whisper. You own nothing.

You were a visitor, time after time.

—Margaret Atwood

◆