As I walked out of the somber rooms of the funeral home into the bright August sunlight, carrying my husband’s ashes, I teetered between two realities: This, now, is him, in his entirety and This has absolutely nothing to do with him.

I had been at Andy’s bedside in the hospice a few days earlier, and I had seen the life force loft right out of him. It was a holy moment. For two and a half days I had sat with him, holding his hand, stroking his cheek, doing ceremony to ease the way to his final transition, talking with him and then, when he lapsed into unconsciousness, only to him. In those minutes after he took in his last breath, before I walked down the hall to notify the night nurse, it had been the astonishing beauty and mystery of the passage that had seized me, how dying was nothing like falling asleep, the comforting image adults give to children to explain death. Nor was that instant of departure a mere collection of physical symptoms—a stopped heart, a sudden settling of the limbs. Andy had left, completely left.

Yet now, as I walked across the parking lot, I carried another incarnation of him: his life-free body, translated by fire into something else. After death, there is a bodily aftermath of death, and this was our version of it, my husband’s and mine: ash.

After untold years of mourning and searching, the goddess Isis at last finds the remains of her brother/lover, Osiris, in the realm of Byblos. His body lies in the sarcophagus that his jealous brother Set had tricked him into trying out for size before nailing him into it. The sarcophagus had floated down the river until it encountered an enormous tamarisk tree, which embraced it in its branches. So enchanted is the king of Byblos by this beautiful, fragrant tree that he has it cut down and refashioned as a pillar, still clutching its divine acquisition, to hold up the roof of his palace. There Isis ceases her wandering to hold vigil, mourning and singing by the entwined phenomenon of coffin, tree, and pillar. She braids the hair of the queen’s maids and scents them with ambrosia, making them so beautiful that the queen entrusts the mysterious visitor with the care of her infant child. At night, when everyone is asleep, Isis lays the baby in a fire to burn off his mortality, while she takes the form of a swallow, circling round and round the pillar. When the queen comes upon this eerie scene one night, she snatches her child from the fire, robbing him of immortality.

A very similar myth arose in Greece as the story of Demeter stopping in Eleusis as she grieves the loss of her daughter, Persephone, abducted by Hades into the Underworld. She, too, nurses the royal child in fire. Her ceremony of mourning and creation is also interrupted when the king grabs back the child and condemns him to an ordinary human life. The similarity of the stories likely comes from the geographical proximity and trade relations between ancient Egypt and Greece. But it is the psychological, cultural endurance of the myth that continues to matter. In both tales, a mourning goddess partners with fire in an effort to empower life.

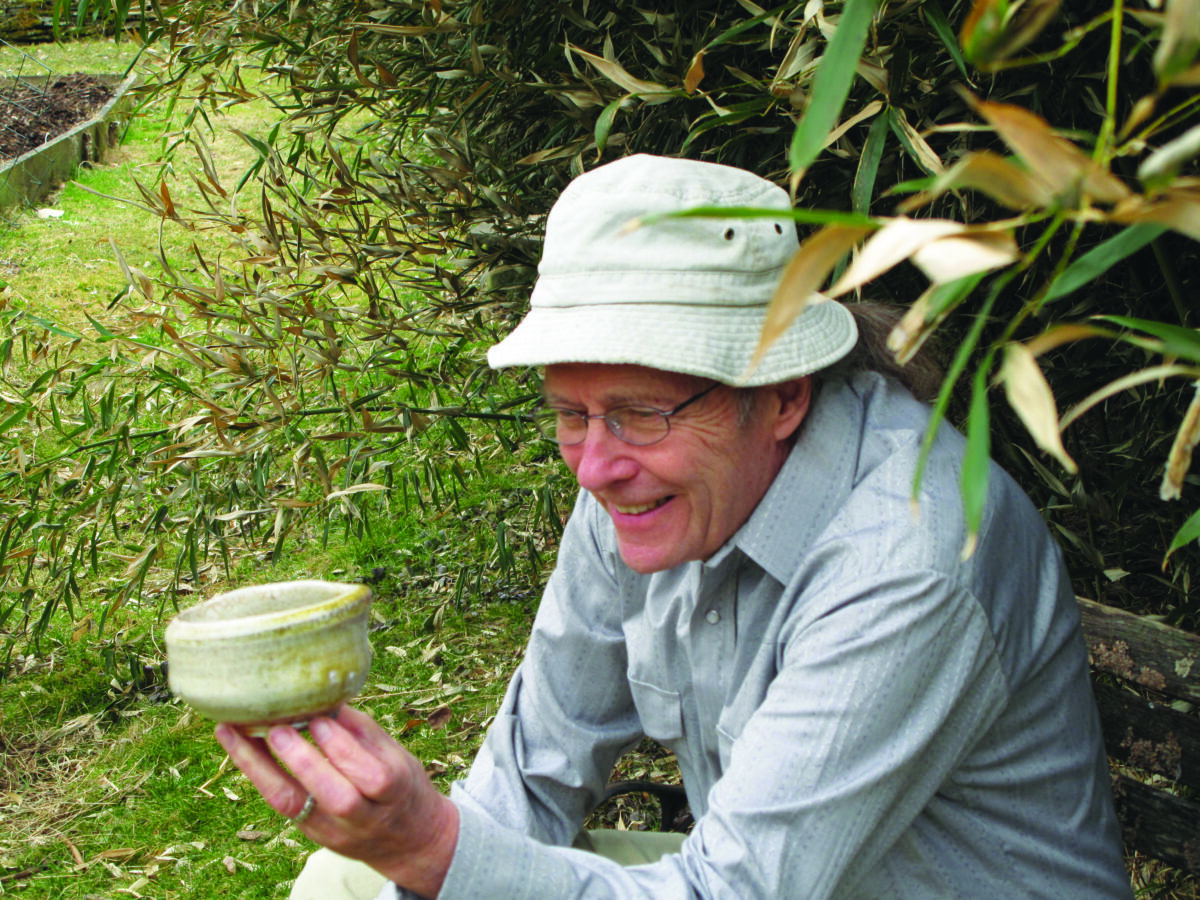

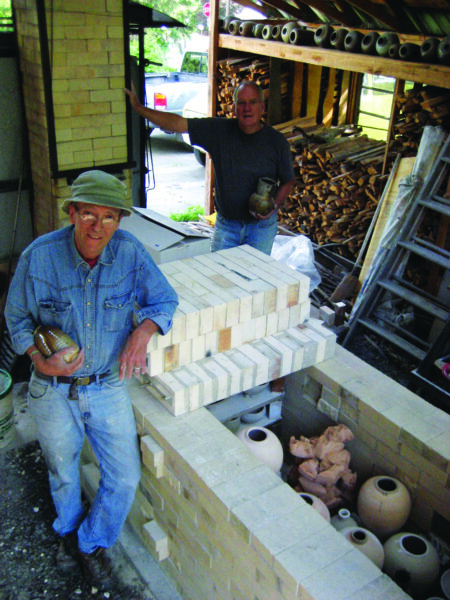

The pot that held my husband’s ashes was one he had made. He and his friend, the artist Phil Sims, had decided twenty years earlier that they would build wood-fired kilns, one in each of their yards in our small rural community of northeastern Pennsylvania. In preparation they read books, made sketches, studied a variety of kilns, and had endless discussions. The supplies arrived—high-fire bricks, metal for the smokestack, pyrometers to track the rise and fall of the heat. They worked for weeks, building the kilns, constructing sheds around them to keep the operation and the operators dry, cutting wood. Over the years, they had dozens of firings. Andy, Phil and his partner, Kai O’Connor, and occasionally other potters and conscripted friends took turns in long shifts of feeding wood into the kiln and monitoring the temperature. You could glimpse the alchemical process by removing a cube of brick from the spyhole to peer into the inferno of creative action. But once the process was underway, the fire was in charge.

As they worked, Andy and Phil would sit by the kiln in battered lawn chairs, drinking coffee and debating. Should they drive the fire with fast-burning locust wood or let it build more gradually with maple or ash? Should they push the temperature higher or close the kiln now? Potters monitor kiln temperature not just with a pyrometer but with cones, ceramic pyramids that are slightly larger and thinner than cones of incense and positioned in a row on a small base. Composed of ceramic materials, they’re designed to start drooping from the tip as the heat builds in the kiln. You can see them through the spyhole as they bend over one at a time until they sag. Phil wanted to aim for Cone 14, or 2,523 degrees Fahrenheit; Andy argued that Cone 13, about 2,455 degrees, was ideal, that higher temperatures burned off the metallic oxide that gave a sheen to the pots. A body in a cremation fire burns at much lower temperatures, around Cone 07, or about 1,800 degrees, the temperature at which you would fire porcelain.

Despite all the disputing and discussions, drawings and evaluations they made, what really fascinated both these artists was the surprises the fire wrought: the way it played over the pots and metamorphosed them into objects of texture, sheen, and color utterly different from the raw shapes that had gone into the kiln. Sometimes the fire caused glaze to drip from a pot on an upper shelf and pool like a liquefied jewel in the pot below, or it painted one side of a pot with scaly ash, while leaving the opposite side with a silky gloss, effects called “kiln gifts.” The firing process also produced what are known as “kisses,” when two pots leaned together in the kiln, and one pot “kissed” its neighbor, losing a bit of its own glaze, which it deposited on the adjacent pot, like a smack of lipstick. For Andy every pot told a story that you could explore by turning the piece around in your hands. Sometimes, he would deliberately reform one side of a pot, cutting into the wet clay and pressing the pieces unevenly back together with his hands. Or he would paint a simple graphic design around the pot, so that the eyes and hands could journey around it together. He knew that he was only the first artist, that fire would take over where he left off. The fire is the master artist, the final arbiter, the ultimate seducer.

T

he myths of Isis and Demeter and the fire-giving life they attempt to impart in the midst of their own grieving remain with us after thousands of years. Why is deep, stabbing grief paired with infancy and immortality? These stories tell us that, even at a time of immense sorrow, we have the power, maybe even the obligation, to take up the care of something new and unseasoned and burn life into it. We do not try to convince ourselves that our grief will be salved by this creative fire. We know we’ll have to keep trudging down the long road of heartbreak, fighting at times even to breathe for one more minute through that terrible loss. And yet, say the myths, we must tend to life, not just after the sorrow wanes, but in the very maelstrom of it.

I didn’t sit long that night by the bed that held the body of my husband. I felt almost desperate to go outside, to inhale the night air and find out if, in fact, I was capable of taking my first steps into a world I would now have to walk without him. After calling Andy’s children and a few friends, I packed our things and drove from the hospice along dark and sleeping roads to the home of Phil and Kai. For hours we sat around the wood-burning fire pit on their deck, drinking tea and telling stories about Andy. The light from the fire illumined our small circle as katydids sang and coyotes howled in the dark woods behind their house.

I

n the modern cremation process, the body, lying in a plain wooden container, is pushed into the cremation chamber. For one and a half to two hours, it burns. Hair, eyelashes, the soft flesh of the inner thigh, the hands that curled to countless tasks, the stomach, the heart, the throat that swallowed food, the tongue that expressed love and wonder, anger and ideas—fire caresses and devours it all. Whereas the fire in a kiln embellishes the shape that’s given to it, a cremation fire dissolves. When I got home with the pot holding Andy’s ashes and opened it, I sifted through the white powder, looking for any trace of his wedding ring, which I had asked the funeral director to leave on his finger. There was no sign of it. Nothing was left but chalky white ash and tiny gobbets of bone.

To hold the ash that is all that remains of your loved one is a jarring experience. It is a thing of no meaning that you feel ought to be meaningful. This is Andy. This was Andy. This is the living transformed to death. I said things like that to myself every time I held that pot of ash—and I couldn’t grasp my own words. What does fire-wrought ash have to do with a human life? Disrobed of life, then taken by fire, a human had become elemental. Still, it was him, and it seemed right that what was left of him rest in a place that would feel like home. I decided that, instead of putting the pot of ashes in some lofty place, like a mantle or a special altar, I would settle it on the back porch, on the old enamel table that he used to pot seedlings for the garden and where he deposited in an old metal cookie tin the dried flower heads and interesting stones and pieces of wood he found.

Fire creates. Fire cooks. Fire kills. Fire also kisses. It kisses death from life and life from death. It kisses shine out of dullness, powder out of solid, black char out of green, moist growth. Fire is radical, potent, and strange. Potters and glass blowers who partner with it are daredevils willing to risk control for magic. Often they sacrifice not just control but the entirety of their envisioned creation, for fire breaks, blows, burns, busts, and shatters if the artist slips up just for an instant—or even if everything goes as planned. An article in Parabola’s 1978 issue on Inner Alchemy quotes Shaikh Ahmad Ahsa, who compares the alchemical process to the making of glass. The process begins when the philosopher-artist fuses silica and potash. If the glass that results is itself fused, it becomes even more brilliant. And if that sparkling crystal is melted once again and the alchemist’s mysterious white elixir is projected onto it, “lo and behold! it becomes diamond. It is still glass and yet no—it is something other but not so, it is certainly itself but itself after undergoing all these trials.” The contents of the pot on the back porch were Andy himself, but himself after undergoing all the trials of a lifetime.

I

, too, turned out to be still myself as I learned how to survive without Andy. I had always thought that, if he died, I would not want to live, but I was wrong. When it seemed that grief was on the verge of extinguishing my own life, I did not hold back. I wailed and wept and hit the bottom, time and time again. And then, oddly but consistently, I would find myself being shoved out of that torturous pit, as if by the grief itself, which, once it gained my surrender, could no longer hold me. I would get up, sit on the front porch and listen to the birds, or harvest the vegetables from Andy’s garden, or call a friend. I saw beauty everywhere every day and felt inexpressible gratitude for the love of my friends.

About a month after Andy died, on the night of the dark moon, I did a vigil in our meadow. I lit a small fire and kept it burning as I spoke aloud to Andy about my regrets, my memories, my love. The pot of ashes rested on a stone opposite me, its chalk-colored sides shimmering in the light of a fire that, this time, did not touch it. As a damp gray dawn spread over the sky, I spread some of his ashes over the trees and bushes we had planted together and that he had so carefully tended, and over the plants in his vegetable garden. I poured ash into smaller pots that I gave to Andy’s two sons and to Phil, and then I wrapped the pot with the remainder in a piece of beautiful fabric.

A few weeks later I started to look for a new home in a different area. Sometimes I wondered if I was rushing things; some of my friends thought so too. But I sensed that those cautions were like the protective instincts of the royal parents in the myths: worry that such a large, combustible action might burn me even more. To me the grief invoked a call of matching intensity in the direction of survival. To ignore it would be to wither into half-life. I also finished writing my new book in those first few months alone and, with my nonprofit organization, created an online Global Day of Mourning for the losses and gifts of the corona virus pandemic. Every day I grieved the death of my beloved, and every day I grappled to grab hold of life. As I got settled in my new home in upstate New York, I decided to buy a green burial plot. One day my unembalmed body will be wrapped in a shroud and laid in the ground. The rest of Andy’s ashes will be buried with me. Ash and bone will sift together as fire, soil, water, and air mix us together in the Earth’s final, ongoing kiss. ◆