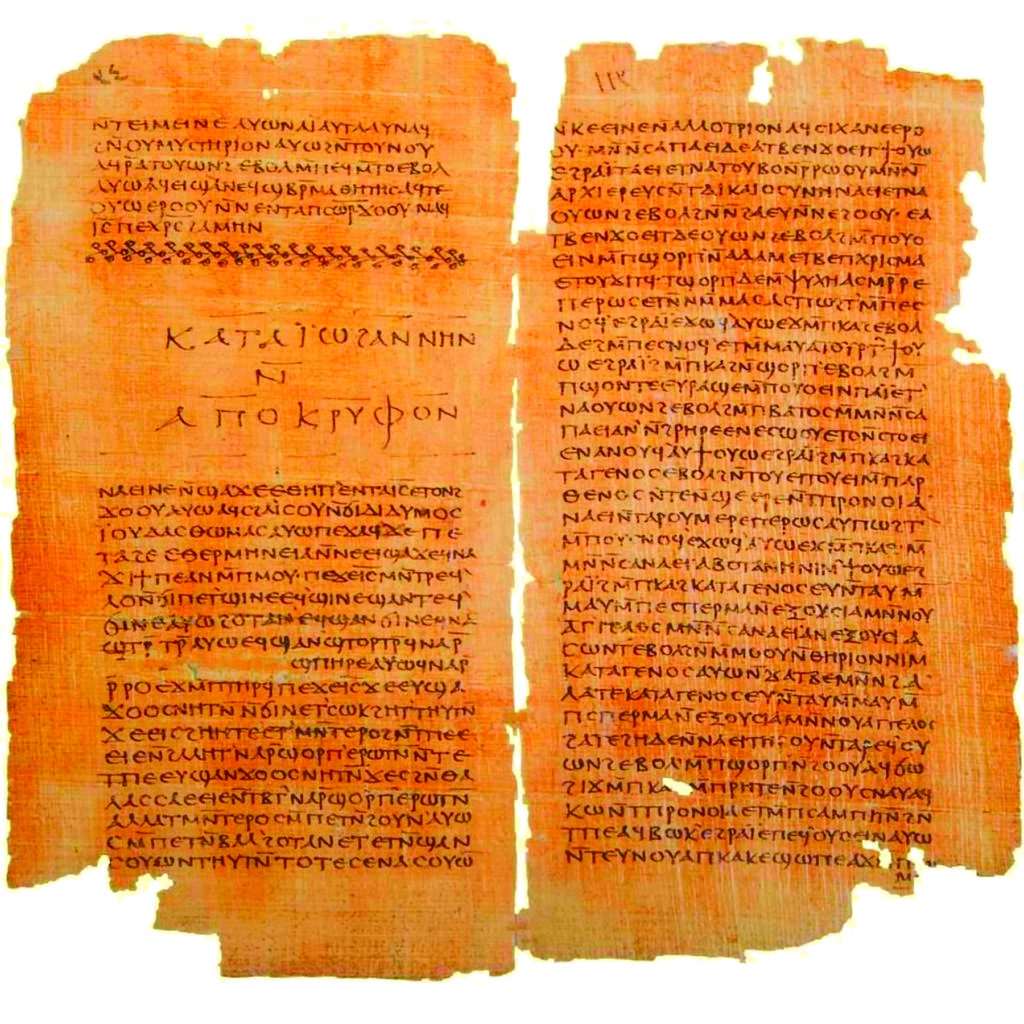

Gospel of Thomas and The Secret Book of John. Codex II The Nag Hammadi manuscript. 2011

As a young scholar, Elaine Pagels breathed new life into the dusty subject of early Christianity in 1979 with the publication of her influential book The Gnostic Gospels. Years later, in the wake of losing her son and, soon after, her husband, Pagels wrestled with religion as she struggled through unimaginable grief. Along the way she wrote many books—including The Origin of Satan, Beyond Belief, and Revelations—and won many awards, including Rockefeller, Guggenhiem, and MacArthur fellowships. Now, at seventy-six years old, she is the author of Why Religion?, an attempt to answer the central question of her life and shed light on why so many of us in the modern world are still drawn to ancient religious traditions.

When we spoke by phone in August 2019, Pagels was in the Colorado mountains, where her family in summers past would accompany her late husband, the physicist Heinz Pagels, for gatherings at the Aspen Center for Physics. She mentioned that for years she had been too grief-stricken at her husband’s death to visit these mountains. But now she had returned. And while she was there we talked about the secret teachings of Jesus, suffering, and how religious traditions are designed to move us toward hope.

–Sam Mowe

Sam Mowe: In The Gnostic Gospels and Beyond Belief, you write about texts that were excluded from the Christian bible, because, you argue, they didn’t align with the set of beliefs that Orthodox Christian founders wanted to promote. What were these texts? Why were they threatening to orthodox Christians?

Elaine Pagels: When I was a graduate student, I was astonished to find out that my professors had all these secret gospels I had never heard about. I thought, what are these things? We were told they were rubbish, that they make no sense, and they’re just a bunch of strange incantations. The attitude was, who cares?

There were fifty texts that were found. Each of those is bound into a very big leather book. The book is about two feet high and it’s about a foot and a half across, these volumes. But each volume contains, say, maybe four or five different texts. And of those, there is the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, the Gospel of Truth, the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, the Gospel to the Egyptians, and so forth. A lot of them are called Gospels; they’re also called Revelation Texts.

As for the Gospel of Thomas, we don’t know if that was the original title because it just starts with the saying, “These are the secret sayings which the living Jesus spoke.” So, whether it was called that or not, we don’t know.

But these are really not meant to replace the ones in the New Testament. They’re mostly amplifying material we find there. It’s not like they’re apples and oranges, apples and rotten eggs kind of thing. The good gospels and the bad ones. But these are meant to be secret teachings and not public teachings. The New Testament Gospels claimed to give the public teaching of Jesus, which he spoke to thousands of people on the hills of Galilee. But the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Mary, the Gospel of Philip, and so on are said to be teachings that were told to certain disciples in private. Rabbis did secret teaching in the first century. They would tell it to you if you happen to be somebody who they considered mature enough to understand it and not getting sort of a swelled head because you think you’re somehow special, or divine, or something like that.

So they would discriminate, and they would only teach it in person. And Paul, the disciple of Jesus who writes before the Gospels are written probably, we don’t know whether he knew the Gospel of Thomas or not; he does quote it at one point. But Paul said he also had a secret teaching. He calls it divine wisdom. And he says that it was secret teaching revealed to him. We don’t know what it was. So, there’s a lot of that in the tradition.

But when orthodoxy is invented in the second to fourth century of the Christian movement, the leaders of the churches, pretend that there is no secret teaching. Bishop Irenaeus says Jesus never taught anything secret, and Paul didn’t either, and neither did anybody else. Even though the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament says Jesus did, and Paul himself writing in his Letter to the Corinthians says definitely that he did, but that he’s not going to write it down.

The reason for that is that if you had secret teaching, or if I had it, we can say well, the real teaching is something different from what the bishops are saying. That’s not the real thing. They got it wrong. It really means this other thing. And you or I could make up crazy or paranoid or bizarre scenarios. I mean, that’s the fear about secret teaching, that people can just come up with something really perverse. I mean, there are people who think God is telling them to kill members of the family, you know?

So, there are reasons why institutions don’t like secret teaching because it can contradict anything they teach. And so the bishops will say explicitly that outside the church, there’s no salvation. So, you’ve got to do it the church’s way, and you have to accept the way the church teaches. And anything else you teach is just basically a terrible error.

SM: What did it mean that gnostic texts were considered heretical?

EP: What Orthodox Christian tradition largely said was wrong with these texts is that they suggest that you have access to God yourself, within yourself and within your own experience, and you don’t necessarily need a church or a bishop, or Jesus even, to find your way to the divine source. You don’t need that at all.

It’s a very different kind of message, speaking to experience and bypassing those kinds of institutions. The bishops didn’t like that, and so they banned gnostic texts. I think it’s a great loss for the tradition.

SM: Since these texts focus more on personal experience and make it easier to bypass institutions, did people who used these texts have communities? Or did they approach their religious lives more individually?

EP: The people who created and loved these texts actually did have groups within various Christian communities or Jewish communities. These went beyond the ordinary group, though. You could be a member of a particular religious group, and then, within that group, there are some people who are interested in secret teaching and want to go further than the others, so they take that into a very different place.

SM: Can you say more about the groups in Christian and Jewish communities that created the Gnostic Gospels? How do we know about them?

EP: It’s hard to know about the groups. But what is very interesting to me at the moment, particularly what I’m rethinking, is what did people remember about Jesus of Nazareth? A lot of people, including the earliest gospel in the New Testament, Mark, remembers that he had secret teaching. And Mark even writes a lot of stories that are meant to have a hidden meaning, and he points out that they have a hidden meaning. And he says Jesus taught secretly to his disciples things that he didn’t tell outsiders and that Mark doesn’t write down.

The Gospel of Thomas, which is the one I find most interesting and powerful, is a list of secret sayings by Jesus, supposedly. We don’t know if it is or not. We don’t know anything, whether any specific saying is actually what Jesus said. But it claims to be the secret teachings. So, there are people who remembered Jesus as a teacher of wisdom, a teacher of secrets. And what fascinates me right now is that the secrets in, say, the Gospel of Thomas, are about Genesis. It takes off from Genesis, from the idea that humans are created in the image of God, and the image of God is spoken about through the metaphor of light, divine light. That suggestion is what will become the heart of Jewish mystical teaching in the traditions of Kabbalah from the eleventh to fifteenth centuries. But they’re not written down before that, although some scholars—and many in Israel, actually—have recognized that what some Christian bishops in the 4th century called heresy, like the Gospel of Thomas, has a lot in common with what Jewish teachers will call mystical teaching or Esoteric Judaism.

So, did Jesus teach that stuff? I don’t know. But there are quite a few witnesses who suggest that he did, and I think that’s really interesting.

SM: How were the gnostic texts discovered?

EP: What was discovered in 1945—and only became available in the 1970s, when I was in graduate school—were over fifty ancient, secret texts. People who knew about the history of Christianity had heard of these texts: The Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Truth, the Gospel of Philip, the Gospel of Mary Magdalene. We had heard there were things like that, but we didn’t know what they were. The ancient sources said, “Oh, well, yes, they’re not really the right texts. These are heretical. These are sectarian and strange and weird and blasphemous.”

When these texts were found, apparently coming out of a monastery library after the bishop had told the monks to get rid of them, they were hidden in Upper Egypt, in a cave, for nearly 1,500 years.

SM: Why are they called gnostic?

EP: It’s the Greek word gnosis, because they don’t ask you to believe in things as much as to come to certain recognitions and insights.

SM: When you were in graduate school, was there anything in the secret texts that answered some of your own religious questions?

EP: Oh yes. The one that really stopped me in my tracks was in the Gospel of Thomas saying number 70: “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” And I thought, oh, you don’t have to believe this; it just happens to be true. It’s a powerful saying. It struck me.

SM: What do you mean when you say that saying is true? What is it about these secret teachings that speak to you?

EP: I took it to mean that what’s true for you or true for me is something you need to discover for yourself. To believe something, it has to be something that really deeply resonates with your sense of truth, and that’s quite different from what a lot of religious people teach. It has to be experientially true. Growing up as I did in this culture, especially as a woman, there are many things you’re expected and allowed to say and feel and express, and other things you aren’t. Most people, in very different ways grow up having to be careful about a whole lot of attitudes and feelings they have. If you learn to keep things inside of you that you’re really feeling and thinking, they can fester there.

The people who thrive and are creative and expressive and strong are the people who allow those things to emerge. I’m thinking of artists, for example, musicians, poets, and politicians. You can see when the work comes out of deep conviction.

I grew up in a culture which was, I thought, very boring and very middle class—I called it “bourgeois” because I was reading French scholars in high school—because you couldn’t talk about all the interesting things.

SM: What are the interesting things?

EP: Sex, money, politics, death, and religion, for starters. Those are pretty interesting subjects. They were the kind of things that often were not discussed, at least not in my family. It’s a particular kind of family that keeps things under wraps and I guess that made me deeply appreciate that kind of saying.

SM: Some of the secret teachings of Jesus remind me of Zen koans, which, in my understanding, function outside of the bounds of logic, and therefore open up spiritual possibilities that arise out of the individual practitioner’s experience and interpretation. Does that resonate with you?

EP: Exactly. These saying aren’t telling you things you’re supposed to believe in. They’re speaking to what resonates with your own experience, as you said. These resonate with experience, not some kind of idea or fantasy or anything else.

SM: One thing that comes through in your writing is that early Christianity was much more diverse than we might imagine. What can the history around orthodoxy and heresy in the early church teach us about living in a modern pluralistic world?

EP: What it opens up for people who have thought of Christianity as the narrow stream of traditions that we’ve known by that name, are all kinds of different ways of reflecting on these traditions, playing with them, and turning them around. There are different versions of stories, different ways of imagining and thinking and feeling, and acting in ritual and poems and songs and stories. It’s like, now you have a much wider range of traditions within Christianity.

SM: Does orthodoxy have any value a modern, pluralistic world?

EP: Well, it certainly has value for some people because it gives them the assurance that they’re on the right track. I don’t value that assurance much myself, but I can’t speak for everyone. I think it was useful to preserve the tradition in a sort of conservative form so that people didn’t add so much junk to it that they distort it out of all shape, you know what I mean?

But your question is an interesting one because we live in a pluralistic world, and so there aren’t many people who are just going to take somebody else’s word for it. I guess authoritarianism still works in a lot of circles, but for a lot of us it doesn’t, as your question indicates.

SM: From a historical perspective, is it more likely that Jesus said what he’s quoted as saying in the secret gospels or in the bible?

EP: That’s a really good question. The problem is: How would we know? Half of what’s, say, in the Gospel of Thomas, is also in the Gospel of Luke and the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament. These are very familiar sayings, like “love your brother” or the parable about the mustard seed. Jesus says, “blessed are the poor,” and things like that. These are maybe the most common sayings, the best-known, common sayings of Jesus. There were lists of those sayings available before the gospels were written, because those sayings were used to compose the Gospels of Luke and Matthew. So, yes, those are very likely to be genuine sayings of Jesus.

With the discovery of the Gospel of Thomas, you find those sayings coupled with sayings we’ve never heard before, which are not in Matthew and Luke, and those are the ones that resonate with my experience, and those are the ones that sound most like Buddhism. So, did Jesus say them? I don’t know the answer to that. I think it’s a real possibility, but we don’t actually know.

SM: You and your husband lost a child at the age of six. How did each of you cope with that loss?

EP: With great difficulty. We had one child, and we were told when he was two years old that he wouldn’t live very long. We adored him. He was a marvelous human being. We had a lot of trouble coping with that, of course. I don’t think there’s anything more devastating that any parent could possibly hear, especially in a world in which the death of a child is a far rarer occurrence than it used to be in the ancient world and even in the 19th century. I was absolutely devastated and crushed for a long time. I don’t know how to tell you that I’ve coped with it. It’s taken years.

You just try to get through one day at a time. We also felt that we needed to find children. We didn’t have other children at the time. We had hoped to, but it didn’t happen, so we adopted two children, because we felt that was something we could do. The way that we loved Mark required us to try to find children who needed parents as much as we needed children, so we adopted two babies. That helped a lot, because I could not think all the time about our son Mark. I had to think about David and Sarah, who were babies, and take care of their needs. That seemed to me a better way of coping with that grief than sort of making an internal shrine that you never get over.

SM: And then, a year later, your husband died unexpectedly. I just can’t imagine going through all of that. How did you get through such profound suffering?

EP: I can’t even imagine it myself. It was incomprehensible, and I couldn’t imagine getting through it myself. It’s amazing to me. I never imagined I would ever write about it or go back to those experiences, because they were just unspeakable. The brain shuts off when you have trauma, it shuts off and closes those things off. That’s pretty much what happened. Only after 25 years, when these children were out of the house, in their 20s, I had to go back and let those experiences emerge again, because if you don’t, they kind of fester.

I began to allow them to emerge and write about them and think about them. It was out of the surprise that I could be feeling alive and well for the most part, even after having had those experiences—I think that’s amazing. It had a lot to do with struggling through them with the resources that come out of the work of studying religion.

SM: Do you think religion is best suited for people who are suffering?

EP: Not necessarily, but it is a way that people have tried to cope with serious difficulties. However, it’s not only that. It’s also a way of dealing with joy. I think these traditions were designed to move us toward hope. When somebody dies, you don’t just sit there and cry. You do a ritual. You remember them. You bring things. You sit with people. You eat. You talk. You pray. Whatever you do. You bury them. All of those are ways that people have learned how to cope with loss. We probably need those a great deal.

SM: What do you mean when you say religious traditions are designed to move us toward hope?

EP: Well, religious rituals are designed for moments of transition. Rituals around birth, adolescence, marriage, and death. All of these transitions involve uncertainty and therefore involve hope. The rituals around these transitions, I think, are meant to strengthen people’s sense of hope.

Take marriage, for example. Marriages, as we know, are pretty fragile structures, or they can be, in our society. The ritual is designed to bring a community of people together to affirm and support a couple getting married. In the marriage rituals that are familiar to me, the community is asked, will you support this couple and their vows? And the congregation says we will. And they all shout that; they’re supposed to shout it. But in any case, whether they shout or not, the people are there to say yes, we affirm and celebrate this union. We recognize it as a social bond, and so forth. That is meant to strengthen the union, to strengthen hope.

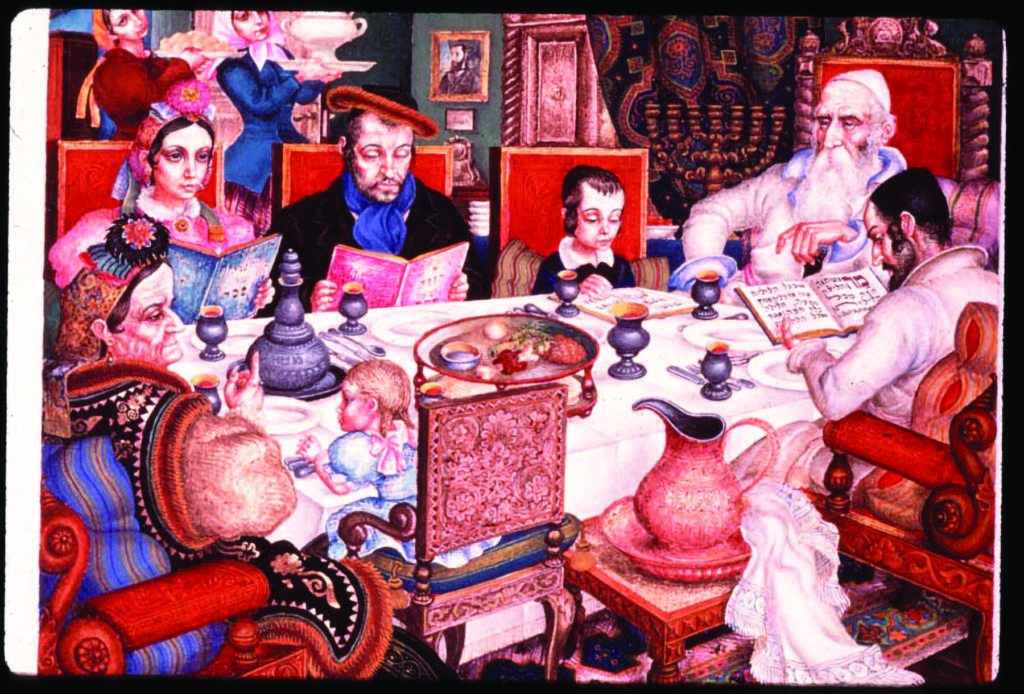

Or take an adolescent ritual, say, the bar mitzvah. It would bring a boy—or a bat mitzvah, a girl—into a community and say oh, this person is now an adult. We recognize this person as a member of our adult community, and we ask this person to read the Torah and interpret Torah for us like an adult, not like a child. And then, after a person can do that, preferably reading in Hebrew and then giving an interpretation, then we say, now you’re an adult, and we celebrate you. We bring you into a new stage of your life. A new stage of your development. That’s also meant to move people toward affirmation and hope.

Funerals also are supposed to move us toward hope, and that’s the hardest one because death is cause for grief. But the funeral is supposed to take you through that grief, and then have the community affirm its own solidarity. And maybe there is hope for the deceased, or at least confirm the family and its connectedness to the rest of the community, despite the loss. And maybe the hope of heaven, you know, or of some joy after death. That’s another possibility.

SM: How much of any religion is actually based in human nature, not in an attempt to regulate or explain that nature?

EP: I would say, from my point of view most of it. Or maybe all of it. Why else would people do this if it didn’t somehow speak to their needs?

SM: Can you give an example of how a person might engage a religious story beyond its literal interpretation, so that it takes on a deeper, more personal meaning for them?

EP: Sure. Let’s take the story of Passover. It’s a wonderful story about the people of Israel, the slaves in Israel, and how God delivers them through these miracles that happen. Is it literally true? I don’t know. But it doesn’t have to be because it speaks to countless people in countless ways about liberation from slavery, from literal oppression, political oppression, social oppression, maybe psychological oppression, I don’t know.

When people do a Passover ceremony and they act out Passover, or when Christians celebrate Easter, and they talk about the resurrection of Jesus and his coming back from the dead. Those rituals are powerful, and they speak powerfully to people’s experience. But it’s not necessarily understood literally.

Here’s another example of how to engage with a religious story beyond its literal interpretation. When I had just come out of graduate school, I met a remarkable teacher of Christianity in New York—he was a great scholar of the early Christian church and a man of luminosity—and when he died, I went to the funeral for him. He was actually laid out in front of us; his body was there, not in a casket, but right in front of us.

And over him, there was the saying, “Jesus said I am the resurrection and the life. whoever believes in me will never die.” And I thought, “Whoa!” I mean, the fact of death was right there. Literal fact, in front of me. And this statement was about the resurrection and the life, and the transcendence of death. Now, I don’t know what that means in terms of what actually happens when human beings die, but it is a statement about death, as my theologian friends would say, not having the last word. And that there are ways that death can be recognized as transcendent. I don’t know if that’s literally true, but I think that’s a powerful statement.

How can religious tradition be literally true when language is symbolic, intrinsically? It just doesn’t make any sense. I think of the language of, say, the Bible. Fables, Psalms, prayers, poems, songs, it’s much more like poetry. T.S. Eliot said poetry is a raid on the inarticulate. And Marianne Moore said poems are like imaginary gardens with real toads in them. I love that, actually, because it’s talking about the fact that the story may be a fable, or an interpretation, but that it’s real in some important way. ♦

If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.