The screen door banged as I sprinted across the yard to a butternut tree that had a limb at just the right height for pulling myself up. I hung by my knees from this perfectly placed limb, swung around backwards and dropped to the ground, landing on my feet. I felt agile and capable every time I did this during my childhood, which was often.

“You always have to put your face in the lion’s mouth,” my mother said at the dinner table. “Always daring.”

I was brave. But my mother said this like it was bad thing, or a mix of good and bad. I was a little girl with a twin brother, shy but also “precocious,” which was also mixed, meaning expressing myself in a way that was celebrated in little boys but was a bit alarming in little girls: being outspoken with teachers, testing my courage and independence all the time. My mother’s tone was warm but also weary, as if mine was a story all too well known. But I knew I was more than this! Like most children, I secretly felt capable of taking part in a much greater story, and the frustration of not being able to express this, the sadness of sitting at a table where people were just passing the potatoes and saying the same old words, locked away in their unseeing private worlds caused me to run outside as soon as I could.

The tree seemed to welcome me. Her limbs were arranged just right for my size. After my spin and drop, I climbed back up, higher and higher. Sheltered by leaves that appeared faintly tropical, I looked down on a green world, feeling wild and good. Stretched out like a wild animlal, breathing and listening to the breeze and the birds, I experienced life pouring in through every sense door. I felt that life was big and vast and full of possibility. What felt like anger and sadness and a wish to rebel inside, was nothing but energy outside. And more. There was goodness in it, a wish to express the joy and possibility of being here.

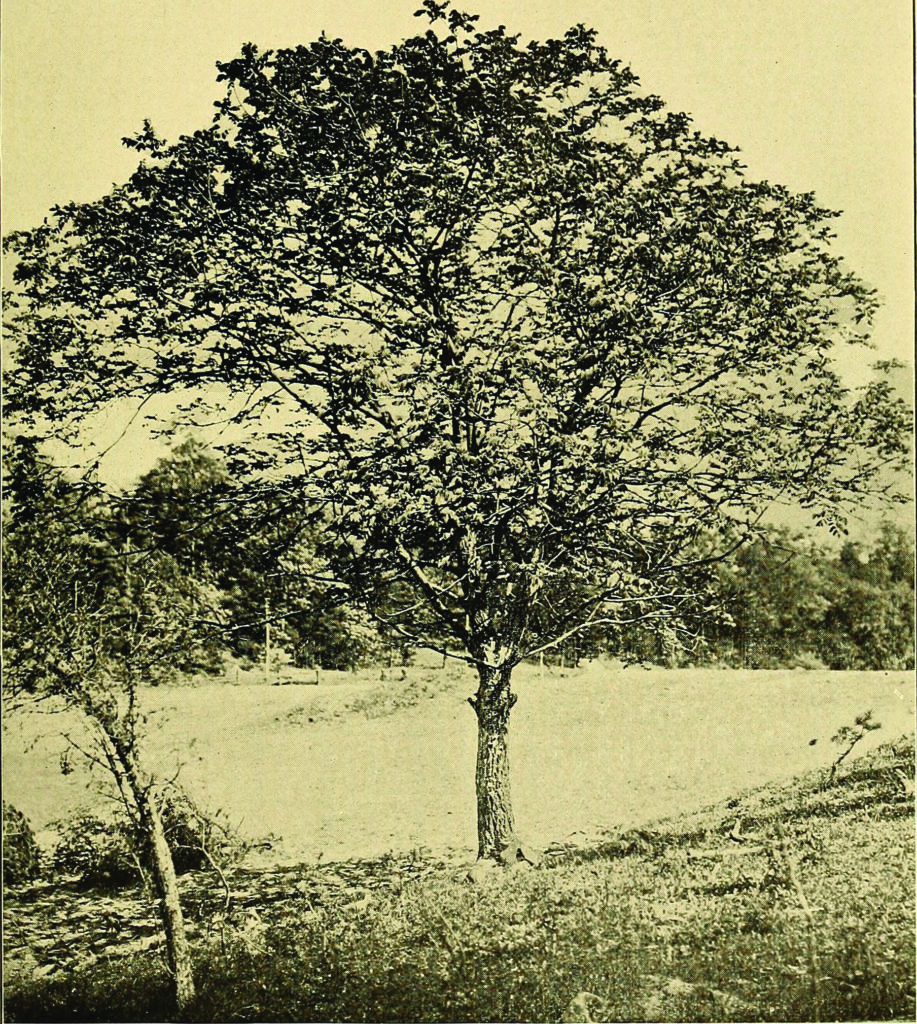

That tree must have been young to have limbs so low. And yet when I visited my childhood home decades later I was shocked to find it gone, possibly due to a canker that is slowly killing the species. That shock revealed to me that this butternut was not just an object but a living being in my life. In her presence, I felt completely accepted, no part excluded, including my wildness. She was patiently and steadfastly there, and in her presence I felt part of the vast kingdom of creation.

In his instructions to those who wish to awaken, the Buddha encouraged them to go off by themselves and sit at the base of a tree, abiding peacefully away from the cares of the world. This detail is often treated as a relic from an ancient time when people spent more time outdoors. But I think it is a rich and relevant detail, since a tree sheltered and supported the Buddha during his awakening. According to legend it even burst into bloom to celebrate the event. And his instinct to take refuge under a tree was rooted in his own childhood memory. Once, the man who would become the Awakened One reached a point where he felt utterly desolate and lost. All his strenuous efforts to find liberation led nowhere, it seemed to him, and he gave up, splitting off from his yogi friends, who considered him a quitter and a failure. The Buddha agreed and let go completely.

In the midst of this letting go, while lying on a riverbank, a heap of rags and bones, in the ashes of his dreams and aspirations, the Buddha remembered sitting under a tree as a little boy. That long-ago child wasn’t doing or being anyone in particular. As his father and other men in the village plowed the fields as part of a planting festival, the little boy savored the joy and freedom of being completely alone in nature. The Buddha remembered that he had a body and a heart and an attention that was not thinking but seeing without judgment, receiving what arises the way that tree received me.

Our bodies, our portion of nature, resonate with nature. We can’t help but see and sense and smell and breathe in life. When we go off by ourselves in nature or in some other quiet place, our hearts remember that life is a gift that is constantly being offered to us. We remember that we are not just a story in our head, urgent and dire as that story may seem. We are not just our painful self-judgments or dark thoughts. We are also part of a greater life and supported by great, benign forces. We tend to discover this when we let go and are like children, seemingly playing at life.

The butternut tree does not have one gender, growing male and female blooms (the female flower yields the nut). Yet that particular tree was maternal, as strange as this would have sounded to me as a child: a tree like my mother at her motherly best. Not every tree struck me as feminine (or masculine, for that matter) but that slender butternut played the role of Goddess of Compassion, holding me in her calm embrace, inviting me to explore my life, assuring me that I was a child of nature.

I had no conscious connection to the idea of the divine feminine in any guise, not even to Mother Earth. We had a boat and camped and liked the outdoors well enough, but no one around me spoke of the earth as a being. We didn’t go in for mysticism of any kind. I remember pining to be Roman Catholic instead of Methodist because Catholicism seemed so exotic, imbued with magic and incense and statues of Mary and many saints. I was mildly interested in the Greek goddess Artemis (the Roman Diana) because she was the twin sister of the brilliant Apollo, but she seemed both too remote and too human.

And yet as a child, I experienced something that would take me years to rediscover: the body is vast. When we let go of who we think we are and just sense how it feels to be here, alive and breathing, we remember that the body is not separate from life but open to it and nourished and supported by it. Air comes in and out; we feel the sun on our skin and smell grass and receive countless other impressions. We are inextricably connected to life, the way trees are connected to each other through networks of fungi filaments.

The Overstory. “The bird and the branch it sits on are a joint thing.” I had no such ideas at eight years old. But I experienced it. I felt different outside than I did inside, and especially when I climbed the tree. Lacking words for the experience,

I used imagination as an extension of my senses and the feelings that flowed from them, exploring the sense of kinship I felt with wild nature.

I pretended I was a wild child living in a primordial forest in India. I knew all the plants and trees in the jungle and communicated with all the animals in their own languages. I was especially close to a super-intelligent and super strong black panther that I named Striker. He was my best friend and protector, communing with me telepathically. Like me, Striker could turn invisible and teleport, and sometimes I could become Striker or he could become me. He was kind and gentle but if necessary he could kill. Inexplicably, Striker and I were both also highly trained, James Bond-like spies. When asked to by the United States government, we would teleport to various European capitals, undertaking missions too delicate and dangerous for anyone else.

Undoubtedly, Mowgli, the boy raised by wolves in Kipling’s The Jungle Book, played a role in this fantasy game, as did Bhagheera, the wise black panther who counseled and protected the boy (it’s wonderful to think that I was indirectly inspired by the Indian Jataka Tales, tales of the lives of the Buddha, including animal lives, before his enlightenment, since Kipling admitted to helping himself to them). I was also clearly inspired by Secret Agent 007. But like all children at play, I was an artist using the materials close at hand. The story I acted out was deeply and truly mine. It was about the wild nature of life, that it was fluid not fixed. I flowed freely from little girl to jungle boy to jungle princess and on occasion to panther to international spy, from visible to invisible, from India to northern New York to Berlin. As a little kid I was limited by adults, but I didn’t feel limited. And in the imaginary game that flowed from my sensations and feelings, in the vastness of the jungle and in my global spy network, in my ability to teleport, I was unlimited.

I once heard that the Aborigines called so-called civilized people the “line people” because we are driven by the delusion that our lives proceed in a straight line. Like all beings living closer to nature, they understood that we live in a web of interconnection. They saw that past and future, including the distant past and distant future, exist in the present moment. The author P.L. Travers, who grew up in Australia, once wrote that all children have aboriginal hearts. They also have aboriginal bodies and minds, and so do adults. Under everything poured into us by our culture and education, there is a capacity to return to our origins. Our body is our original home, and a gift from our distant ancestors. Bringing our attention home to the moment-by-moment life of the body, our breath and sensations, roots us in life, quietly leading on to deeper feelings and essential truths.

The word imagination comes from an ancient root that means to copy or imitate. When I played a jungle game, I believed I was doing more than just trying on roles from books and movies. The game followed the wisdom of the body and felt experience. I was exploring the fluidity and interconnection of life.

“Something marvelous is happening underground, something we’re just learning how to see,” writes Richard Powers in The Overstory. “Mats of mycorrhizal cabling link trees into gigantic, smart communities spread across hundreds of acres. Together, they form vast trading networks of goods, services, and information….”

Science is slowly rediscovering what ancient people once knew. It is known that trees are more than separate objects that happen to give us oxygen and absorb carbon dioxide. They are linked and constantly communicate, helping each other in the face of their challenges. And more. In the ancient legends of the Buddha’s awakening, the tree he sat beneath greeted him, bloomed for him, details that once seemed like a Disney cartoon. And yet there is some scientific evidence now that trees really may be able to sense our presence, emitting fragrances and even changing shape slightly in response to us. This suggests that they aren’t just communicating with each other. They are helping us.

Our bodies can sense what people once knew. Our hearts, which ancient cultures held to be the seat of consciousness, still know how to open to the world around us, to feel wonder and love. Deep down, under all the words and stories, we know we are not alone here. Usually, our thinking takes up all the attention, endlessly repeating what we think we know. It doesn’t trust that the body and the heart can discern essential truths. But in a time of overwhelming uncertainty, even confirmed atheists may find themselves looking up at the sky and the trees, thinking, “Help me.”

In times of crisis, there is often an instinct to be alone at times, to sit quietly or go walking outside, feeling our feet on the ground, space all around. The body innately seeks contact with the earth because we are part of the earth. It senses the life that is being offered to us moment by moment, literally breathing it in through every sense door. It knows innately how to open to a greater world. And given enough time, the heart also opens, feeling the inexpressible preciousness of what the body senses, revealing another kind of mind under our ordinary thinking mind, a mind that loves what it sees, and feels part of it. At such times, we stop being line people and become like children or indigenous people who haven’t forgotten the Goddess.

According to legend, the boy who would be Buddha pretended to be asleep under that long-ago tree. Once his minders went off to watch the plowing festivities, he sat up and crossed his legs in meditation posture to experience the joy of solitude, the joy of not needing to defend himself or acquire anything, the joy of being no one in particular, just open, flowing experience. As a little girl, I too was exploring how it felt to be fluid, not fixed, not separate but part of life. Remembering the tree that supported and inspired me, I realize that I was actually being helped to an essential truth. I was invited to experience being part of something wondrous and mysterious and vast. I got to feel what it is like to be free from separation, not in control of life but in harmony with it, adding my perspective and various pretend skills of spy craft and jungle knowledge and teleportation and what not to the very real feeling I had for life. I imagined what it can mean to serve, to have my life and expression come from a sense of connection. What else could that butternut be but a goddess, a messenger from a greater world? ♦

From ParabolaVolume 44, No. 4, “Goddess,” Fall 2019. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing. Four times a yearParabola has explored the deepest questions of human existence. Without your support, we would cease to exist. Please consider helping us by making a donation.