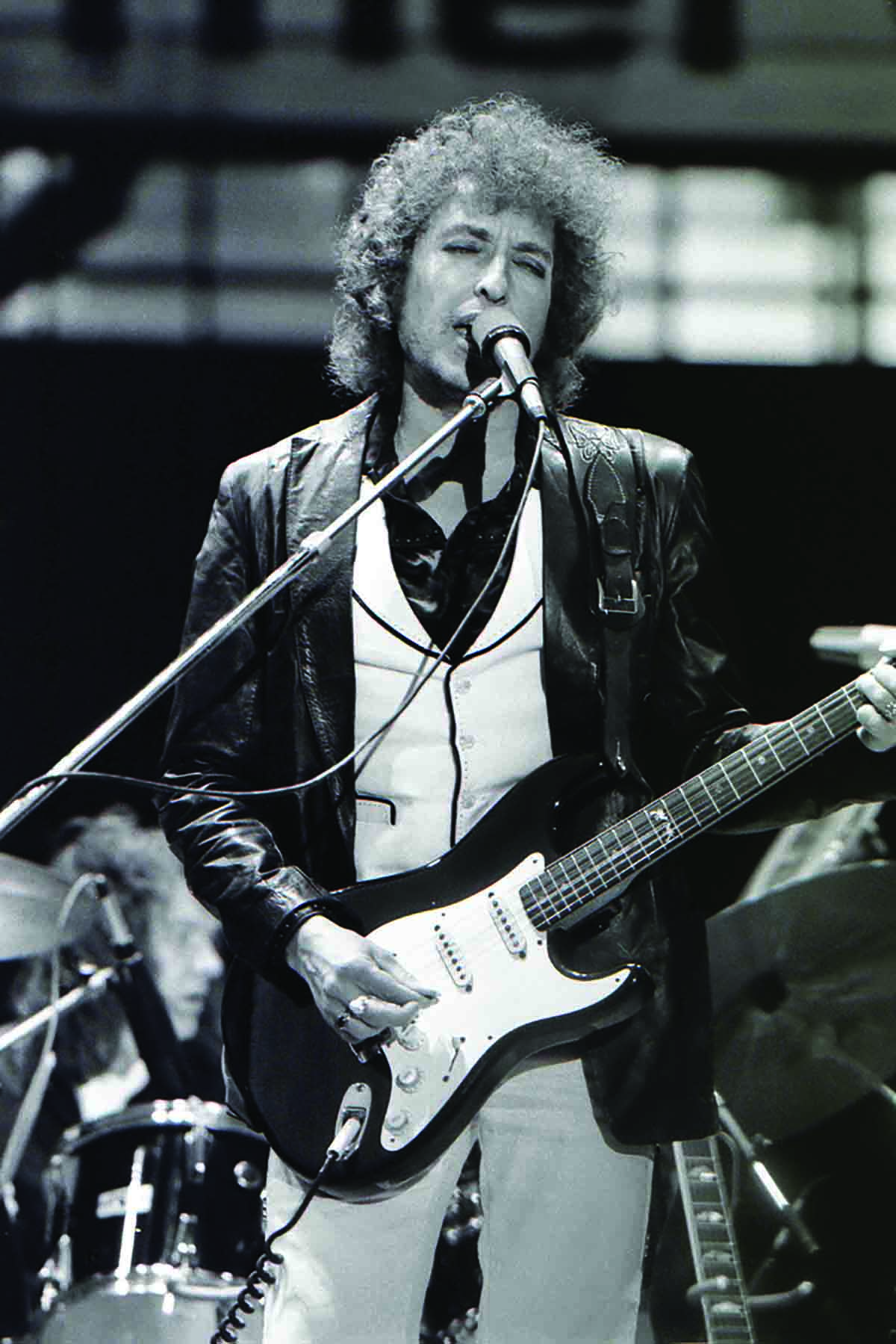

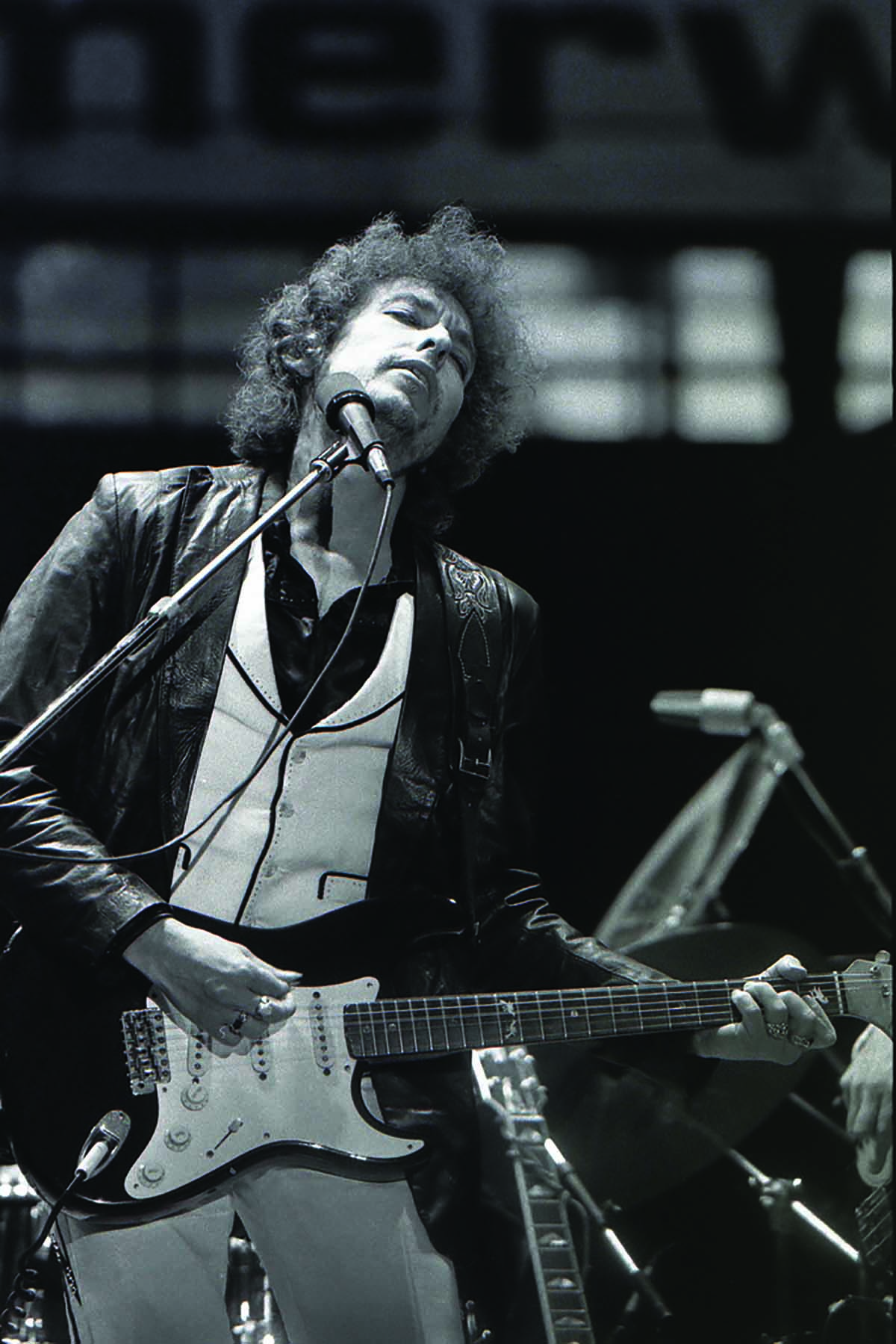

Born Robert Allen Zimmerman in 1941, Bob Dylan has been a celebrated and revolutionary social figure for the better part of sixty years. He’s maintained a glittering career, has inspired generations of musicians, and has even been awarded our culture’s highest accolade for Literature.

Thinking of Dylan, however, multiple images arise. There is the pasty-faced young folkie. Then at warp speed, the protest singer had moved on to the speedfreak who dabbles in surrealism. And once Dylan tired of the touring and the image-making, he’d quickly transitioned into a crooner-and-country family man. Within a decade, he’d become a paint-covered cocaine vagabond and even a born-again Christian. That was forty years ago, and he hasn’t stopped changing since. But behind the frames of shifting identities and appearances, one image has remained stubbornly consistent in Dylan’s evolution—that of the deified feminine, or the Goddess.

In Chronicles, his often impenetrable but compelling autobiography, Dylan credits Robert Graves’s The White Goddess with provoking his initial interest in “invoking the poetic muse” When he first read it, though, “he didn’t know enough to start trouble with it, anyway.”1

Even from its initial release in the late 1940s, The White Goddess had been received as a peculiar and arresting text. Graves was known mainly for his series of poems from the First World War, but he maintained a long fascination with the poetic Muse, a figure he envisioned as an all-embracing and dangerous matriarch.

Submission to this red queen wasn’t just a literary game for Graves. To taste of her wine of “mixed exaltation and horror” was conceived as “the function of poetry” and a spiritual exercise in “religious invocation.”2 To Graves, the “true poet” dabbles not in surface imagery and mere observation, but experiences an almost suffocating intoxication with the true feminine within. To see, hear, and feel her thoughts without resistance, and to externalize her vision into a deft and accessible form, is perhaps the highest state that any human can achieve.

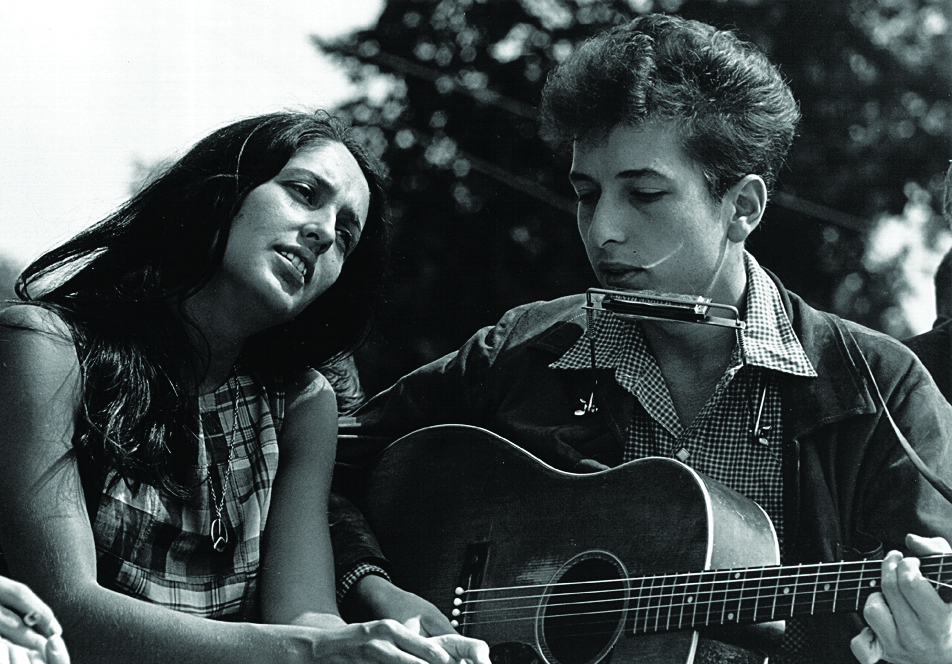

Where Dylan’s early albums Freewheelin’ and The Times They Are-a-Changin’ offered contemporary critiques of America’s dark institutions, his attentions after reading Graves were drawn increasingly to the voices in his own head. To listen to them, it would take another peculiar poet, one with his own special ideas on the Muse.3

More than a wordsmith or an artist, Arthur Rimbaud saw himself as a “visionary.”4 For Rimbaud, the role of the poet was not to make pretty rhyme or tell a compelling tale, but to unearth the higher truth in everyday objects. He was set into motion by Baudelaire and his Symbolist Manifesto and led a new vision that balanced the ideal with the material. Where the Realists had fallen into a drab neutrality, and the Romantics a hallucinatory escapism, Rimbaud and the French Symbolists saw the world around them as a vessel for deeper symbolic appreciation. Objects are not to be seen in and of themselves, or cherry-picked and denied in favor of a God. They are nothing less than media to universal truth.

In the revealing light of Symbolism, America’s dark institutions were more than problems of political process. The real problem behind the “obvious targets” was “squareness” of any and all kinds.5 But more than the social misery it can create, squareness—seen in America’s closed minds, phony attitudes, word games, and everything in between—stands as a barrier between the human subject and its connection to “une passante,”6 or the moment of connection to the Goddess Muse.

Dylan didn’t take much convincing. He was done with protest songs for protest. He was finished with romance for romance. He was even dispensing with rock ‘n’ roll, or at least the square kind. Perhaps unlike any artist before or since, Dylan was now in the game of “vision music.”

The first signs of Dylan’s new revolutionary approach can be seen

in “My Back Pages,” off 1964’s Another Side LP.8 Where Rimbaud dreamt of “unrecorded voyages of discovery and untroubled republics,”9 Dylan’s personal vision speaks of “Romantic facts of musketeers” and dispenses

with the surface distractions of “memorizing politics.”

He’s moving past the “front page news” of explicit politics and self-aggrandizing marches. Away from the facades of the coffee shops, Dylan is ditching folk in favor of a move to his own “back pages”—the storeroom of perceptions, memories, and images with which he can forge a subjective relationship with the Muse.

Dylan’s sixth album, Blonde on Blonde, was released just two years later and marks possibly his greatest achievement as a musical artist. Even according to the Nobel Committee that awarded his Prize, this is the album with which one should begin when venturing into Dylan’s work.10

Blonde on Blonde was released after Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited, two albums that spelled Dylan’s first ventures into an “electric” sound and a growing connection with the Muse. In songs like “She Belongs To Me” and “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” the Muse is presented as “The Artist”—a Rimbaudian image of modernity11 draped in Zen-style koans and varying digs at empty squareness.

It would take Blonde on Blonde, including the song “Visions of Johanna,” for this Muse to become a Goddess.

Al Kooper—the band’s organist—explained that Blonde on Blonde is 3 A.M. put to music. In more poetic terms, Dylan says it sounds like “thin, wild mercury.”12 In every wobble, squeak, drag and rush the music serves “Visions of Johanna” with singular purpose. Johanna’s vision is plain to see.

Compared to other tales of interwoven lovers, Dylan’s seems distinctly less romantic. Curled up in bed and “entwined” with Louise, Dylan feels more alone than ever before. He lies in silence, resigned to the ambient noise of a city night in a depersonalized haze. “Ain’t it just like the night, to play tricks when you’re trying to be so quiet? We sit here stranded, but we’re all doing our best to deny it.”

He surveys his surroundings and takes a careful note. “Lights flicker from the opposite loft” and “heat pipes just cough,” as a “country music station plays soft.” The music is so ingrained and undistinctive that it’s almost become a continuous feature of the room— it “plays soft, but there’s nothing—really nothing—to turn off.”

We’ve all felt like Dylan. We’ve all been with the wrong person. Yet Dylan’s portrait seems to lack much passion either way. He doesn’t hate her, adore her, or offer Louise a description of any particular intensity. Where she’s not offering him heroin and “tempting [him] to defy it,” Louise is “alright—she’s just near.” He doesn’t resent her. He just resents how she makes him reflect. Like a good Symbolist, Dylan sees Louise as a perfect projection of his own fatal complacency. “She’s delicate, and she seems like the mirror.” Not just a mirror but the mirror.

Dylan’s response isn’t to tell Louise his true feelings. He just lies there and thinks, captured by fantasy. In an obsessive rumination, he dreams of an ideal woman he names Johanna. With a Goddess like Johanna, one wonders whether Dylan should just cut his losses and go to sleep. While her “visions conquer [his] mind” and he drifts further from his real relationships, all Dylan can do is stay “up past the dawn” and fret compulsively on what he doesn’t have.

Dylan doesn’t mind Louise. She may even be who’s really best for him. But once he’s caught in Johanna’s psychic trap, all Louise does is make it “all too concise and too clear that Johanna’s not here.” It doesn’t help that “little boy lost” keeps reminding him, either. As much as Dylan may have tasted of her inspiration in “Mr. Tambourine Man,” another exercise in near-daybreak inspiration, Johanna has since said her “farewell kiss” and left him behind.

And while he may complain of the boy’s “muttering small talk at the wall,” Dylan’s self-pitying fantasies don’t seem too different—for every complaint and fantasy, the “ghost of electricity” seems more and more inaccessible. Perhaps it’s just as well that Graves’s White Goddess was far from a loving mother. In mixing the Goddesses of Hell and Earth with Heaven, the White Goddess’s triumvirate is an indelible mixture of death, life, and rebirth.

Coming to Johanna may be the goal of his poetry, but Dylan should beware that he doesn’t lose what he already has. In the subsequent verses, he goes on to expand her ambiguous glow to the world outside his apartment. He focuses first on a fairly desolate scene of wandering prostitutes and gossiping “all night girls,” whose games of “blind man’s bluff” face a quick disruption from a busybody “night watchman.” As he “clicks his flashlight” and does his time, however, the watchman seems to strike a kind of existential crisis. When no harm is done and no roles really need fulfilling, “is it him or them that’s insane” when he breaks up their game?

This death—comparable to what Thomas Hardy called la petite mort—doesn’t apply just to New York’s rain-swept streets. Even the museums, society’s centers of truth and art, are exposed as merely human exercises in category-making and social pretension. Johanna is a Goddess, and how can we expect to understand her? As “infinity goes up on trial, voices echo, ‘this is what salvation must be like after a while.’” Even Mona Lisa “musta’ had the highway blues” in our silly schemes, “’cause you can tell by the way she smiles.”

The museum’s patrons aren’t too promising, either. They’re a strange mixture of a “primitive wallflower,” some sneezing “jelly-faced women,” and a “mule” packed with colorful adornments of “jewels and binoculars.” But where such scenes may seem ordinary or even admirable, in our human pursuit of truth, all Johanna does is “make it seem so cruel.”

By the song’s climactic verse, Johanna’s role becomes apocalyptic. Dylan is tired of his inadequacies, and he’s sick of a world consumed by squareness. “My Madonna, she still has not showed,” he complains, as her “empty cage now corrodes.” Something is happening soon enough, though. “The fiddler now steps to the road” and draws up Johanna’s final balance sheet. “Everything’s been returned which was owed,” the fiddler writes, as Dylan’s “conscience explodes.”

Like a folkie John the Revelator, Dylan receives his final vision of Johanna. In place of the angel’s deathly trumpets and God’s bellowing call, we hear “the harmonicas play” and “the skeleton key in the rain.” His ego has been swept aside. Dylan has laid down his “weary tune,” just as he’d hoped to three years before.13 Perhaps it really is mystical. Perhaps Dylan is achieving some higher state. But when “all that remains” is his “vision,” one wonders whether Dylan has sacrificed even his own identity to an obsessive fantasy.

“Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” is the album’s final track. It’s one of the first songs in mainstream recording to take up an entire side of vinyl, and its near twelve-minute runtime precedes the progressive experiments of bands like Pink Floyd and The Beatles. While “Johanna” may have been solely inspired by a late-night fantasy trip, “Sad-Eyed Lady” was genuinely recorded in such a context.

Over the course of several hours, Dylan was holed up in a room at a Nashville studio writing words obsessively. His band mates had little else to do than sleep, play cards, smoke, and drink as Dylan wiled away. On his eventual re-emergence, he gave them a fairly singular welcome.

“This is the best song I’ve ever written,” he declared.

If “Johanna” marks the high point of the “thin, wild mercury sound” he long sought, “Sad-Eyed Lady” has to be a close runner-up. Built on a plodding funereal waltz, Dylan’s whines mesh with humming organs, wailing harmonicas, and careful drums to create a wash that stands almost suspended in time. I often find myself wondering, at the song’s end, how that time had passed so quickly. The march is so entrenched, and the instruments so deft and compelling, that the song is genuinely hypnotic.

As with most Dylan songs, though, the hymn’s true depth lies in the words. He may call to a “Sad-Eyed Lady” and list her with dozens of attributes, but it’s not even clear she’s a Lady. By the litany’s end, we’re really no closer to probing who this Goddess is or what she represents at all. Like her sister Johanna, the Lady materializes Dylan’s tastes for lovers and literature in a Symbolist adaptation of prayer. She’s the “back pages” brought to life.

Any big fan of Dylan knows that “Sad-Eyed Lady” was written for Dylan’s new wife, Sara Lownds. As if her name isn’t evidence enough, he confessed as much in his song “Sara,” released ten years later in the aftermath of their bitter divorce. Like a throwback to “She Belongs to Me” and “Love Minus Zero” from 1965, the Goddess in “Sara” is a “radiant jewel” and a “mystical wife”—a “Scorpio Sphinx in a calico dress,” sent to Dylan by a “messenger” in the “tropical storm.”

Everywhere throughout his portrait, Dylan’s Sad-Eyed Lady is peppered with varying references to Sara’s real life. She has the “child of the hoodlum wrapped in her arms” and a “magazine husband”—hints at the child she’d had with her first husband, a magazine photographer—and she’s blessed with the “sheet metal memories of Cannery Row,” an image that mixes her father’s job as a sheet metal worker with the title of a John Steinbeck novel.

At the same time, the Sad-Eyed Lady is presented in unambiguously religious terms. In the first verse alone, we’re introduced to her “prayers like rhymes” and “voice like chimes,” and the “mercury mouth” from way back “in the missionary times.” On top of her “silver cross,” the Goddess is adorned by “saint-like face” and “ghostlike soul,” and a “holy medallion” that her “fingertips enfold.” Yet the Sad-Eyed Lady doesn’t seem particularly joyous or radiant in her mysticism. She has a “face like glass” and “sheets like metal.” Her “deck of cards” is even “missing the jack and the ace.” Whether any of these similes are derogatory, we don’t know.

She’s so abstract that she stands beyond description. One wonders whether her eyes are even sad, or if she’s really cast away in those lowlands at all.

We don’t know because Dylan never gets to meet her. In ‘She Belongs To Me,” Dylan could at least give the Artist a “big drum” for Christmas. With the Sad-Eyed Lady, he’s just left outside. All he can offer are the tentative gifts of “warehouse eyes” and “Arabian drums” at the “gate” where “no man’s come.” In the Odyssey, one of Dylan’s greatest literary influences, Penelope presents Odysseus with visions of two competing gates: the Gate of Horn and the Gate of Ivory; behind only one can the hero find truth and the embrace of the Goddess. As for which Gate Dylan chooses, it’s left unclear to the end.

The references to the Odyssey don’t finish there. Just as Penelope’s court became consumed by con artists and tricksters in Odysseus’ absence, the Sad-Eyed Lady is presented as a perpetual magnet for time-wasting suitors with terrible intentions. Dylan’s competitors variously “impress,” “mistake,” “destroy,” “persuade,” and “outguess” the Goddess, and even try and lay “the blame” on her for a group of murdered “dead angels.”

Some of these suitors are the “Kings of Tyrus,” who come to her with a “convict list” in anticipation of arrest. As another projection of Dylan’s “back pages,” this image refers to Tyre, a now-Lebanese city mentioned indirectly in the Old Testament. Ithobaal I was one such great king of Tyre. He fathered Jezebel, a bewitching siren who appears almost the polar opposite to the Sad-Eyed Lady. Where Jezebel leads the Israelites away from Yahweh and towards false Gods, the Lady stands as a gentle beacon to truth and exploitation in equal measure.

And while it’s her “gentleness” and “geranium kiss” that allow such hucksters to enter her life, it’s precisely those qualities that save her, too. Like the “raven” with a “broken wing” from “Love Minus Zero,” the Sad-Eyed Lady’s vulnerability and contingency belie her very ability to be a Goddess at all—namely, to be communicable and stand as a muse to the inspired artist.

Dylan explores Sara’s “gentleness” in “Shelter From the Storm,” a song off 1975’s Blood on the Tracks that’s similarly peppered with biblical imagery. Like earth prior to its creation, Dylan stood as a “creature, void without form” before meeting the Goddess. Struck with “exhaustion,” “steel-eyed death,” and “mournin’ doves,” Dylan even compares his square, unfulfilling life of drug abuse and “Louise” to the pains of Jesus’ passion. People “gambled for [his] clothes” and “bargained for [his] salvation,” as a “crown of thorns” tore deeply and opened up his wounds.

If not identical to Him, Dylan claims that the Lady is His equivalent. As much as he wants to “turn the clock back to when God and her were born,” the Sad-Eyed Lady is hardly a perfect Goddess. She may dress like a nun mystic, but she’s also seen with “curfew plugs” and “basement clothes.” Her voice may ring “like chimes” yet she swears with a “cowboy mouth” and sings “matchbook songs” from pulp fiction stands. And just as the “sunlight dims” and “the moonlight swims” in her ethereal gaze, she projects in pedestrian visions of “streetcars” that she “places on the grass.”

Whether Dylan should leave these gifts by her gate is never established. Not once in the entire song does she ever answer him. Like her sister Johanna, the Sad-Eyed Lady is reduced to the hallucinatory cast of mere vision. The Goddess stands within and without him. She’s a Symbolist projection of his own tastes and experiences, and reflects back correspondingly to the deep flaws of the square world around him. She’s a kaleidoscope—a paradox, even—of competing and mutually reinforcing images that commands and resists definition.

Dylan’s Goddess is no ordinary Goddess. She’s not an all-consuming demon like Kali or a mournful icon like the Virgin Mary. And neither is she a symbol of pure creativity like Jung’s anima, or a mytho-historical emblem like Graves’s The White Goddess.

In listening to his Muse and looking to the symbols of his own “back pages,” Dylan was heeding Rimbaud’s call and divorcing him at the same time. For Dylan’s Goddess was not Rimbaud’s, and neither was she Graves’s. His is a genuinely subjective relationship, and one that he and he alone can understand. ♦

From Parabola Volume 44, No. 4, “Goddess,” Fall 2019. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.

1 Bob Dylan, Chronicles, Vol.1 (2006), Simon & Schuster, 45

2 Robert Graves, The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth (1948), New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 9-10

3 Timothy Hampton, ‘Absolutely Modern: Dylan, Rimbaud and Visionary Song’, Representations 132, 1-29

4 Arthur Rimbaud, Illuminations, XXX

5 Hampton, 5

6 Charles Baudelaire, ‘À Une Passante’, accessed at https://fleursdumal.org/poem/224

7 What would you call your music?

8 I like to think of it more in terms of vision music – it’s mathematical music. – taken from https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/bob-dylan-gives-press-conference-in-san-francisco-246805/

9 Hampton, 5

10 Arthur Rimbaud, Season, 49

11 https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/oct/13/pop-lyrics-arent-literature-tell-that-to-nobel-prize-winner-bob-dylan

12 Hampton, 5

13 http://www.bobdylancommentaries.com/blonde-on-blonde/

14 Bob Dylan, ‘Lay Down Your Weary Tune’ (1963), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-1Vi9y2q3Y