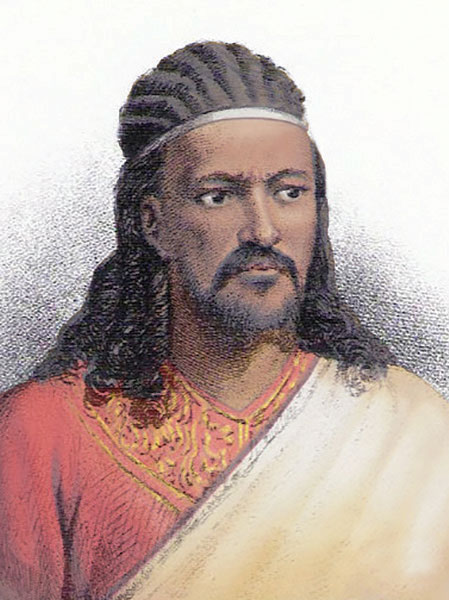

of Abbas Antonios, Ethiopia. Late seventeenth century. Musée

du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris

In the Era of Princes, Abyssinia had no king. It had an emperor in name alone, locked in his fortress to the north. He wore a crown of gold and bore the blood of King Solomon, but he did not rule. Instead, he was ruled by his regent, who in turn tried to rule over the warring princes spread across the land.

Abyssinia knew no peace.

One of those princes lost his title when he lost his father. He fled his homeland, known as “the taste of honey,” for school where he learned poetry, history, and the art of war. But his new home fell under the rule of another prince and he ran once more, lest he lose his head like he lost his crown.

With the cunning he had learned, the prince became an outlaw and the master of an army. He soon caught the eye of the emperor’s regent, who offered the emperor’s granddaughter to the prince as a wife, hoping to bind this warrior to the line of Solomon.

But our prince had two secrets.

First, there was the prophecy: it was said that one day a prince would return greatness to Abyssinia as a true ruler over a united kingdom.

Second, there was the blood: he too was a son of King Solomon.

Our prince would see himself shrouded in myth. And so the prince of poetry and war overthrew the men in power and became the true Emperor of Abyssinia.

His rule spread like wildfire, pushing the very boundaries of the kingdom. He built alliances with those in Abyssinia and those far away, and all sent tribute to this promised prince. Even the most powerful queen in the world gifted him a pistol, gleaming metal and wood.

He wanted that modernity lit by gunpowder for Abyssinia, but his borders were a shifting line, rebels within and without. Soon, the prince needed help. He wrote to the kingdoms beyond the sea, his hope lying with his friend, the powerful queen.

But no help came. The prince’s patience grew thin. He locked up subjects of that fateful queen, hoping to get her attention. Surely she would not abandon a fellow servant of Christ.

He succeeded. The queen noticed and sent her armies to invade Abyssinia. The emperor released his prisoners, but the queen promised him only life in captivity.

He was a promised prince. His myth could not end in a cage.

On Easter Monday, April 13, 1868, Emperor Tewodros II shot himself with Queen Victoria’s gift pistol. His became a new myth: one of an independent Ethiopia outside the control of imperial Europe. Still, the British armies came, torching his fortress and churches and looting as the city burned to ash. It took fifteen elephants and two hundred mules to carry the bounty to their ships.

One British soldier cut off two locks of the emperor’s hair while painting his deathbed portrait and brought them home to England. The emperor’s son, Prince Alemayehu, was also taken as a souvenir, first in the care of the explorer Tristam Charles Sawyer Speedy and later of Queen Victoria herself. She loved the boy and was devastated upon news of his death at age eighteen, when he died alone in the cold Yorkshire moors.

“It is too sad!” she wrote in her diary. “All alone, in a strange country, without a single person or relative belonging to him…. Everyone is sorry.”1

The story of Emperor Tewodros II is all but forgotten in Britain, but in Ethiopia, his legend is one of epic proportions. Plays, songs, and memory have kept Tewodros alive in the Ethiopian canon. But the loot from the British Expedition to Abyssinia and the aftermath of Tewodros’s suicide still largely remains in British collections.

In March 2019, however, locks of hair taken from the emperor were finally returned and reinterned at his tomb in Ethiopia. In a powerful ceremony in London, the cultural minister for Ethiopia, Dr. Hirut Kassaw, received the locks, proclaiming that “for Ethiopians, these are not simply artifacts or treasures, but constitute a fundamental part of the existential fabric of Ethiopia and its people.”2

Terry Dendy, Head of Collections Standards and Care at the National Army Museum, where the locks had been held since the mid-twentieth century, explained the decision in a brief letter to the public:

“Having spent considerable time researching the provenance and cultural sensitivities around this matter, we believe the Ethiopian government claim to repatriate is reasonable and we are pleased to be able to assist. Our decision to repatriate is very much based on the desire to inter the hair within the tomb alongside the Emperor.”3

In a letter meant to be merciful, there is the edge of an imperial sword. This was a decision for Britain to make, not Ethiopia. But to whom should the emperor belong?

The West is wrestling with its colonial heritage in the most literal sense: its museums teem with treasure taken on conquests abroad. Crowns and swords, books and bones. The breadth of culture ripped from its home is hard to comprehend, as is the sheer scale of it: ninety percent of Africa’s art is held on other continents.

Imagine the Liberty Bell gone, Versailles stripped of its Hall of Mirrors, the Roman Forum empty of columns and stones. To see them, you would have to travel across seas, deserts, mountains; apply for visas and buy a ticket for a glance at your people’s history behind glass. Spread that theft to Asia, the Americas, and even other corners of Europe. The scope is unimaginable, as are the emotional scars left by the absence of national treasures.

“This is not just about the return of African art,” Prince Kum’a Ndumbe III of Cameroon explains. “When someone’s stolen your soul, it’s very difficult to survive as a people.”4

![King Theodore’s [Tewodros’s] Bible. Manuscript written

on vellum, tooled leather binding. Wellcome Library, London](https://parabola.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/King-Theodore’s-Tewodros’s-Bible.jpg)

on vellum, tooled leather binding. Wellcome Library, London

The question of what to do with objects collected during the colonial period is gaining traction with those beyond museum curators. Around the time of the return of Tewodros’s hair, President Emmanuel Macron of

France announced, “I cannot accept that a large part of the cultural heritage of several African countries is in France,” and declared that the return of colonial collections would be a priority for his government.5

While many see it as a moral or philosophical question, the repatriation of collections is also a legal one: many governments have laws preventing the breakup of national collections, no matter their provenance.

There have been several attempts to work around this. Some have turned to loans, by which objects can be put in displays in their country of origin while technically still belonging to colonial power who took it. Though not a perfect solution, it offers a first step for many people to reclaim their history.

But it is not only treasure that was taken, as seen in the case of Tewodros’s hair. Groups from around the world are campaigning for the bodily remains of their ancestors to be returned to their rightful resting places. In America, the leggings and hair of Sitting Bull were returned by the Smithsonian to the Native American leader’s descendants in 2007 after years of campaigning.6 Across the world, museums and scientific collections are being pressed to return the remains of Indigenous Australians, many of whom were disinterred for research up through the 1940s.7

Items of spiritual significance are also at the heart of these fights. The Rapa Nui people of the Easter Islands have been campaigning for the return of their world-famous moai, or Easter Island head statue, which currently stands in the British Museum. The moai represents a deified ancestor and is believed to have brought peace to the island a thousand years ago.

“It embodies the spirit of an ancestor, almost like a grandfather. This is what we want returned to our island—not just a statue,” explains Carlos Edmunds, the president of the Council of Elders.8 The pain in its absence can be felt in the statue’s name: “Hoa Hakananai’a,” meaning lost friend. It was renamed after the British took it in 1868.

But there are many who oppose the repatriation of collections. Museums turn to provenance to support their claim to items, pointing to the legality by which they were purchased. The most famous case is that of the Parthenon Marbles, which were collected by Lord Elgin in Athens and are currently housed in London. While Greece continues to demand their return, the British Museum argues that Lord Elgin collected them “with the full knowledge and permission of the Ottoman authorities.”9

Others worry about the safety of objects if moved from their current homes. Museums can be looted or burned down, as was the case of the National Museum of Brazil in 2018, where as much as ninety percent of the collection was destroyed. We must protect the world’s heritage. Would returning objects threaten their survival?

There is one argument against repatriation that stands out amongst the others: those from both sides of the discussion who want only some

work repatriated, while other pieces remain in the world’s most eminent museums alongside Western masters. Sent back home, heritage might be forgotten, but next to Rodin, Da Vinci, and O’Keefe, all countries may be seen on the world stage. The British Museum uses this argument in their claim over the Parthenon Marbles, highlighting that if returned to Athens the statues would be “appreciated against the backdrop of Athenian history” while in London they are “an important representation of ancient Athenian civilisation in the context of world history.”10

Are the world’s top museums, then, the curators of worth?

There is no question that museums do important, irreplaceable work, and that far from all collections are built from stolen goods. But as we begin to question who owns the past, more questions arise about museums’ role in the current world climate. Are they the rightful guardians of our heritage? Or are they the last bastion of empire, clinging to treasure under the guise of a moral code?

Many of the arguments against repatriation echo with racist tones, like that of the safety of objects. New museums are being built across the world, like Museum of Black Civilizations in Senegal, to modern, safe standards. It is true that the museum burned in Brazil, but so did Notre Dame in Paris. Can anywhere truly promise survival for these ancient artifacts?

Similarly, the legality of purchase is questionable if one side was a conquering force backed by the strength of an empire. What fair agreement can be made with with a war machine in the negotiations?

There is forgiveness to be sought in these great museums, but beyond them, too.

of Abyssinia, 1868. Photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron

One misty spring day in England, during her visit to collect Emperor Tewodros II’s hair, Minister Kassaw stood silently in the catacombs of Windsor Castle, a wreath laid by her feet. Nearby, a brass plaque reads, “I was a stranger and ye took me in.”

She stood for minute’s silence in honor of Emperor Tewodros II’s son, Prince Alemayehu, who is buried in the castle’s St. George’s Chapel amongst the kings and queens of England.11 Since 2007, Ethiopia has requested the return of his body so that he might be interned alongside his father, but so far they remain rebuffed by Queen Elizabeth II, who says that while she sympathizes, the prince cannot be exhumed without disturbing the sanctity of the others buried with him.12

There is no easy path to heal the trauma of our entangled histories, so intertwined by the brutal reign of empires that our dead are forced to share the same grave. But there is a reckoning coming that we cannot ignore: to whom does history belong? And who will choose its future? ♦

1 “Prince Alamayu.” Royal Collection Trust, 2019, www.rct.uk/collection/themes/trails/black-and-asian-history-and-victorian-britain/prince-alamayu.

2 “Ethiopians cheer as London museum returns plundered royal hair.” Reuters, 2019, https:/af.reuters.com/article/topNews/idAFKCN1R21BV-OZATP?feedType=RSS&feedName=topNews.

3 “National Army Museum responds to repatriation request from Ethiopia.” National Army Museum, 2019, https://www.nam.ac.uk/press/national-army-museum-responds-repatriation-request-ethiopia.

4 “Return of African Artifacts Sets a Tricky Precedent for Europe’s Museums.” New York Times, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/27/arts/design/macron-report-restitution-precedent.html.

5 “France urged to change heritage law and return looted art to Africa.” Guardian, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/nov/21/france-urged-to-return-looted-african-art-treasures-macron.

6 “Smithsonian Returns Sitting Bull Relics.” New York Times, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/18/arts/design/18arts-SMITHSONIANR_BRF.html

7 “The bone collectors: a brutal chapter in Australia’s past.” Guardian, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/14/aboriginal-bones-being-returned-australia

8 “Easter Islanders call for return of statue from British Museum.” Guardian, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2019/jun/04/easter-islanders-call-for-return-of-statue-from-british-museum.

9 “The Parthenon Sculptures.” British Museum, 2019, https://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/news_and_press/statements/parthenon_sculptures.aspx.

10 ibid

11 “Ethiopia Requests Remains of Prince Alemayehu.” allAfrica, 2019, https://allafrica.com/stories/201903260747.html.

12 “Give back our stolen prince, Your Majesty: The Queen sparks diplomatic row by rejecting Ethiopia’s plea to return ‘lost king’ buried 140 years ago at Windsor Castle.” Daily Mail, 2019, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7018909/

From Parabola Volume 44, No. 3, “Mercy & Forgiveness,” Fall 2019. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing. Four times a year Parabola has explored the deepest questions of human existence. Without your support, we would cease to exist. Please consider helping us by making a donation.