Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Movie going as spiritual practice

At moments I wished I’d picked a different film. The opening scenes were peaceful enough: a tiny hermitage on a raft floats in a lake in a deep valley in the Korean wilderness; a little boy and an old Buddhist monk row a fancifully painted wooden boat to shore to forage for herbs in the forest. The old man warns his young charge to watch out for snakes. But it isn’t a snake that will poison this unspoiled garden.

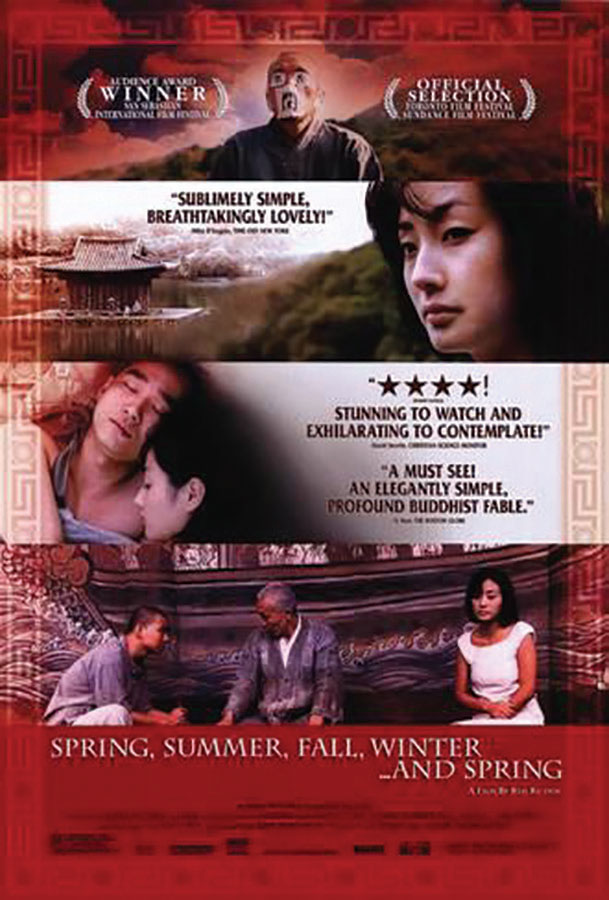

Friends sat here and there in the darkened theater, watching Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…Spring by South Korean director Kim Ki-duk. I had seen them come into the Jacob Burns Film Center in Westchester, bundled in scarves and winter coats, smiling at the novelty of so many of us from our meditation community out at the movies together to watch my selection in the Burns’s annual Meditative Life film series.

The evening felt quietly festive, as if the theater was a kind of temple and we were there to observe something special. In our meditation group, once or twice or dozens of times, I had reminded people that contemplate comes from the Latin templum, or temple, which was originally a place for observation, for reading the signs, divining how things would go. And this film showed the way things went, the seasons of a life passing, innocence giving way to experience, actions always leading to consequences, sometimes cruel.

I had pictured people settled in their seats, expecting an escape from their complicated lives in cold New York, and not much in the way of drama. Instead, in this film they would have nature red in tooth and claw. And the real wildness would turn out to be in human nature, and in the director himself, who—I’d learned only after selecting his film—had stood accused of real violence, including rape.

“Rarely has a movie this simple moved me this deeply,” wrote the film critic Roger Ebert, who included the 2003 film on his list of great movies. The program director at the Jacob Burns Film Center, Brian Ackerman, who had invited me to select a film and a related theme, also remembered the film as gorgeous and powerful. But what did the alleged actions of the director mean to the film? In the end, I decided that the movie still stood as a parable about awakening compassion. And yet as I watched it with my friends, I felt waves of resistance. My brain froze, fought, and thrashed, as if I was wrestling a cartoon alligator.

This steady stream of comments and judgments distanced me from the actual experience of watching the film. In a brief talk I’d given before the screening, I invited others to see exactly this reactivity. I spoke about film as a way of awakening compassion. To feel compassion, we must awaken our own nature. The key is including everything that arises in body, heart, and mind. And here was a film and a director demanding that we see life whole.

Watching movies can be a spiritual practice. Our lives, including all our loves and pursuits (among them going to the movies), are a spiritual path, not a poor substitute for monastic retreat but exactly the right conditions for awakening the heart. And movies have a power to show us that we are not what we think, that just like the images on the screen, we are fluid, not fixed.

“To study the self is to forget the self,” said the great Zen sage Dogen. “To forget your self is to be enlightened by the ten thousand things.”

Losing ourselves in a good story, we experience a stream of impressions and reactions: fear and empathy, judgment and compassion. Movies show us new worlds and perspectives, but they also show us our own true nature. If we are paying attention, we find that we are fluid, a stream of changing responses, not fixed and separate from the world we see and hear. We startle and fear for the characters on the screen. And at times, our hearts open.

Watching a movie can be like finding ourselves in a dream. Dogen compared awakening to dreaming. This comparison seems strange and paradoxical to contemporary people in the West because we associate dreaming with falling asleep and being unconscious, and waking up with a crisply defined state of consciousness. Sati, an ancient word for the mindfulness that so many people seek, literally means to remember the present moment. Sleep is forgetfulness.

But true awakening involves forgetting as well as remembering. Deep down we understand this seeming paradox. We have moments when we forget ourselves, when we leave the cramped attic room of our thinking and come down into the life of the body and just see and experience life in the present moment. But in those moments, we discover that we aren’t isolated observers but receivers and responders, not separate from the ten thousand joys and ten thousand sorrows of life.

Usually our dreams are very simplistic—we have too much baggage to make a difficult journey; we are lost in a strange city. But even these dreams remind us of what we are in essence, that we don’t just think and know: we are creatures who sense and feel our way in the world. Deep down we know that the true wilderness is beyond and known, and we really don’t know very much. This essential vulnerability is the wellspring of our compassion.

Contemporary Buddhist teacher Pema Chodron builds on this, teaching that the more you open to what is happening (even at the movies), the more your boundaries dissolve. “The journey of awakening happens just at the place where we can’t get comfortable,” she writes. “Opening to discomfort is the basis of transmuting our so-called ‘negative’ feelings.”

Our brains are hardwired to avoid this—to fight or flee or freeze out discomfort. Judgment is a one-way street, and most of our thinking are forms of that, comparisons, discernments, opinions, all designed to keep us safely cordoned off from what we are seeing, assuring us that what we are perceiving can be safely labeled as known.

To truly awaken, we must dare to enter the unknown.

Dogen also compared Buddhist practice to a circle. Each moment includes not just the present but also the past and our intention for the future. In Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…Spring we watch the boy become a man. He causes suffering and learns there can be no escape from the consequences. Well into the film, the old monk directs his young charge to carve the verses of the Heart Sutra into the wooden planks of the raft, while driving the anger, the impulse to fight, flee, or freeze, from his heart.

The Sanskrit name of the Heart Sutra is Prajnaparamitahrdaya, which roughly translates as “the perfection of the heart of wisdom.” According to legend, the verses were recited to an assembly that included the Buddha by Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all the Buddhas.

The most famous line in the Heart Sutra is: “Form is emptiness, and emptiness form.” There is nothing in this world that is fixed and unchanging. Everything depends on other things, which means there really is no way to split off and be separate.

There is no escape from the consequences of our actions because everything we think and do is shaped by what arises. But this also means that there is nowhere else to go for liberation. The possibility for awakening is constantly before us here and now.

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Viewing the film while noticing what was happening inside was like walking in a forest among wild things: fleeting fears and sorrows and anger appeared and disappeared; at other moments arose love and a wish for healing, for the righting of the world, a restoration of peace. On screen, as the old monk gently aged, the young man was radically changed by his experience. As the seasons passed, he was literally played by different actors. Yet he kept coming back to this still place.

I sat in the darkened theater, noticing how often I longed to do something, to fast-forward past the difficult parts, to rewind and change things, to freeze the serenity and beauty. It felt quietly daring to just sit, opening to what presented itself without pushing for a particular result. It was enlivening, to see how clumsy and ignorant most of my thinking really is, a kind posturing, applying known labels, planting a flag in the wilderness. But at moments, I saw that this mental busyness is sleep, and that seeing this is the beginning of awakening.

At the end of the film, the young man returns to the monastery he’d left years before, no longer young and clearly roughed up by life. He is at this point played by the director himself. The English word suffer comes from a root that means to bear. The old monk has passed away and the director takes his place as resident monk, learning to practice and serve, finally climbing a mountain while carrying a weight representing the suffering he has caused. But he carries it along with a statue of Kuan Yin, a female form of the bodhisattva of compassion. At this point it becomes clear that the film is an almost physical gesture, an embodiment of the director’s own wish for redemption and liberation.

Kuan Yin is left standing on a mountaintop, looking down at the lake and the hermitage and forested valley and beyond. She sees the big picture, the ten thousand joys and the ten thousand sorrows. Nothing is outside the circle of her seeing and her compassion. Her name means, “She who hears the cries of the world.” The director comes down from the mountain and cares for a little boy who has been left at the monastery, who is shown shaking a box turtle, his own first act of unthinking cruelty.

“I just realized something,” said one moviegoer after the film. “The old monk was once the young monk.” We stood smiling and nodding at each other in the lobby, as if we had made a tough climb and now stood together admiring the view. In retrospect, it was clear that the wisdom of the old monk came from living through hard things. He too had suffered and caused suffering, and had carried this consciously until it was no longer a burden but a source of strength and compassion.

A friend emailed that she could barely speak afterwards. She asked me why I thought it took so long for the statue of Kuan Yin to come out of its cupboard. I guessed that compassion, that an enveloping view that doesn’t judge us, tends to come when we call. But we tend to call only when we really need her. ♦

From Parabola Volume 44, No. 2, “The Wild,” Summer 2019. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing. Four times a year Parabola has explored the deepest questions of human existence. Without your support, we would cease to exist. Please consider helping us by making a donation.