By age twelve I’ve learned umpteen natural methods to combat my nearsightedness. These include the dictates of the Bates method via Aldous Huxley: eye exercises, palming, imagining a darkness against which to rest your eyes—a family friend making us kids giggle with his tales of a very dark pair of trousers floating on the Black Sea. Meanwhile I flounder to the bottom of my class from not seeing the blackboard, while the world turns blurrier and blurrier…. Until I finally meet that miracle shared or loathed by so many others: the first pair of glasses.

My handsome Uncle Agand at his clinic in Tambaram, South India. Having put the correct lenses into a heavy old contraption and making sure I hold it steady on my nose, he takes me past the people waiting outside his office. Smiles dazzlingly at them in apology: “Just for a minute….” Then when we’re at the open front door he points to a lone tree across the bare grounds. For the first time it’s not a far green blob. Every difference or detail yielded from upright trunk to rounded branches is distinct and demarcated. It is that amazing thing: a tree. And then as now, Uncle Agand has always been my hero and always will be, past his death or mine: the man who vanquished distance to show me the shape of a leaf.

Now into my eighties in the United States, with macular degeneration spreading into my remaining good eye, I’m knocked into another realization. At breakfast one Sunday morning the world turns crooked. There isn’t a straight line in it. Refrigerator, kitchen counter, cabinet, toaster… every single edge of every single thing is a blotch or a squiggle. Even digits on the clock-face curve, like Salvador Dali’s clock dribbling over his horizon. This occurs in my right eye, and my left can’t see beyond the now-crooked peripheries of a blur. Of course it’s petrifying. And lasts for some hours. But even as a (hopefully) temporary aberration it has become a strange discovery of sight: what you suddenly see when you cannot see.

Then, at the other extreme, there is the matter of visual memory—whether familiar or unfamiliar, whether as a first glimpse, or layered over the years. My mother’s visual recall is the earliest I know, in both senses of the word. She remembers being rocked as a baby (in 1908) in a cradle hung from a wooden frame. As the cradle swung she saw the shadow of its frame move back and forth, back and forth, across the ceiling.

By the time we are adults some of us have realized the deep and abiding blessing of sight as sustenance—for the eye of the artist, as for a deep dimension of the spirit. Sweep of cloud and coast and water; shadow of a leaf on a rock; the mood, movements and quietude of light across sky and earth, and all the wild creatures upon it. Yes, and anguish at seeing its decimation.

Of true seeing, J. Krishnamurti says in his Notebook: “To see there must be humility whose essence is innocenct (sic). To see with eyes that have been bathed in emptiness, that have not been hurt by knowledge—to see, then, is an extraordinary experience.” Yes, once more. Memory, preconception, everything, does fall away in the total and utter focus of such moments. You fall away yourself, there is only what you see.

Commenting on such a consummate experience, the wisdom texts of the Upanishads speak of the observer becoming the observed, of both dissolving into the same unity—a transcendent unity, if you like. But seeing, here, is indeed ‘spiritual’ (that debased word) when it can evoke such a spontaneously rapt and given meditation. Krishnamurti again: “The beauty of the evening absorbed all thought.”

For me there remains, after such totality, a residue of gratitude. I want somehow to convey whatever I have received or grown from, to record the fullness of sight before I lose it. So I attempt doing this in words, when no longer able to work professionally in visual art or photography.

In trying to integrate their inner and outer vision, other artists go far beyond courage in facing what has happened to them. Three women I know have done this: diving deep, deep dow—almost embracing this new reality—not only to fulfill their creative need but to enhance its chosen form of expression.

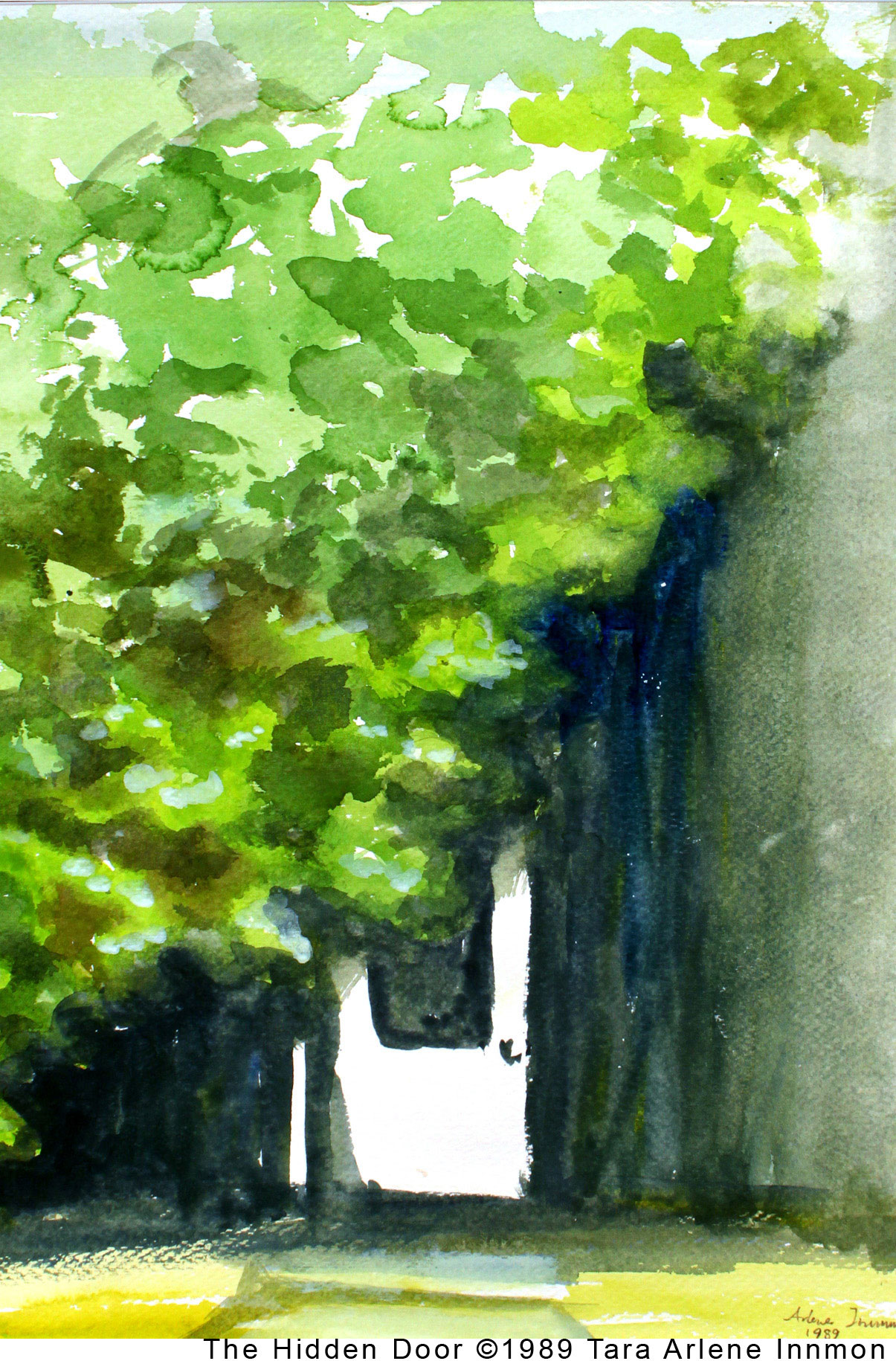

When Tara Arlene Innmon started to grow blind she painted her world in its different stages of visibility. Her pastels and water colors capture a vivid blur of people in a bus; a tree-shaded neighborhood door has turned into the dazzle-white entrance to a troll’s house; her dining room becomes an exquisite abstract in saffron and earth tones flecked with blue; and finally even the chairs in her doctor’s waiting room are transformed into the shapes and subtleties of dark to grey to misty white. “(There) I found that I really only saw areas of dark and light in washed out colors. My mind was filling in for me what I knew would be there. I couldn’t even see what I drew on the paper, but I hoped my knowledge of working with pastels would help me make it close to the way I saw it.”

Sylvia Rudolph shares her experiences, specifically as an artist, in the human process of confronting vision loss. “When I lost the sight of my right eye I also lost the ability to judge my placement in space. How high is the curb I’m stepping down from? How far is the car ahead of me? Is it staying the same size or getting bigger QUICKLY?” After a few years of adjusting to her single point depth perception she moved to a new importance of light and dark. “While drawing a portrait of my son with a white pencil on black paper, I noticed I was drawing the light on his face and in the background, and ignoring the dark. Had I switched to drawing what was indeed more visible? I spent the next several months drawing on dark paper with white pencil or crayon, and concentrated on looking at light more consciously.” This, she finds, has helped both her art and her enjoyment of the visual world.

Individual responses to such black/white contrasts are an important parameter for low vision readers as well. A series of psychophysical studies, led by Gordon E. Legge at the University of Minnesota examined the effects of Contrast Polarity—i.e., black-on-white vs. white-on-black text —in low vision reading. In cases where readers preferred the latter, this preference was related, among other factors, to abnormal light scatter in the eye. Similar responses under similar conditions also occur in those diagnosed with genetically inherited retinitis pigmentosa.

Meet lovely Mai Rose, performing artist and writer of a unique one-woman show, The Liminal Being. Mai’s diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa came early. “When I was four years old my mother knew something wasn’t right. I started moving slowly around the house after coming indoors on a bright day. At dusk, I ran my hands along the walls to find the open doorway.” By her late teens she has enrolled at the Iowa Department of the Blind to cope with her disability. Of that time she says” “I have learned to travel with a cane and read Braille. I can use a table saw and make a seven course meal, completely blindfolded.” Now, as her sight decreases further, she says she steps daily into a new world that “shifts and changes like shadows on a late October afternoon. “

The Liminal Being also reveals how Mai Rose has bridged polarities of other, very traumatic, life experiences— between feeling “like a stranger in my own story” to arriving at some extraordinary, almost mythic thresholds of insight and perspective:

“When we say someone was ‘kept in the dark’ we know this to mean that they are ignorant of the situation. When someone is depressed or angry we may even call it a ‘dark’ mood. Darkness is also where evil lurks, in the urine stained alleys of men’s souls. And so, our first response to darkness is to fear it and banish it at all costs. But darkness is our sister, our brother, our father, and our mother. Germinating seeds can only reach for the light after nestling in the deep. And let us not forget, all of human life begins in the dark of the womb, surrounded by the sound of our mother’s heart. This is beauty, this is my dark”.

Inspiring examples can guide our footsteps. Research gives us its spectrum of hopes, milestones, testaments pro and con. New state-of-the-art equipment and aids to sight are being invented all the time, staggeringly imaginative as well as practical—though who across the world can access these, or how many can afford them, remains as always a crucial question. I, for one, am infinitely grateful for unpleasant injections in the eye which now keep me from going blind; but all bets are off if insurance won’t cover them next year.

Yet we still have those invaluable companions along the journey, sharing other resonances, discoveries and textures of experience across time. In the earlier years of the twentieth century author Katherine Mansfield speaks of going out and looking at a tree and coming back plus the tree. To Jonathan Swift, writing in 1726, “Vision is the art of seeing things invisible.”

Further back we have a whole heritage of Hindu texts that encompass a much more profound context for what is now broadly called the mind-body connection. By 400 CE the famous aphorisms of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras hearken back to sources from much earlier philosophic traditions. Ancient observers have already recognized that thought is a force as strong as gravitation or repulsion.

The Yoga Sutras show us how to harness this force: “Yoga” in Sanskrit means “union”—at multiple levels in the flow of all life, from the transient to the timeless. Four words of a single sutra by Patanjali can take us through a full sweep of awareness: from the definition of consciousness and our fluctuating states of mind, through whirlpools of thoughts and impressions, to a union of physical and mental processes that can still the spirit (and, for some, join it to its eternal source.)

Of course any paraphrase is inadequate. But the great sage Patanjali understood connections. And acted upon them as nobody else did. In addition to his matchless Yoga Sutras, his treatise on Ayurveda remains a daily treasure trove for herbs and natural medicine; and his classical treatise on grammar explores the lore of language implicit in human communication—thereby helpful in healing, as in so many other fields.

Crystallized against all this background, I hear my beloved mother again. She once said , with neither modesty nor conceit: “Don’t worry about my eyesight. I’ve been granted clear inner vision. That will do.” ♦

Bibliography:

Legge G. E., Rubin G. S., Pelli D. G. and Schleske M. M. (1985b) Psychophysics of reading. II. Low vision. Vision Research. 25, 253-266.

Mai Rose, The Liminal Being, Dreamland Arts Theater, St. Paul, MN. December 7-10, 2017, January 10-13, 2019.

If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing. Four times a year Parabola has explored the deepest questions of human existence. Without your support, we would cease to exist. Please consider helping us by making a donation.