They meet by moonlight, rising out of lakes and ponds or drifting down from the branches of birch trees, hair drip-ping with dew. Their corpse-pale skin reveals their inhuman nature. Their watery essence links them to ancient, elemental forces. In Russian and Ukrainian tradition they are called the rusalki, and they belong to the spiritual world of women, as the mythology surrounding them testifies. For not only do they bring the fertilizing spring rains when invoked by village maidens, but they also punish any man who chances upon them, using as a weapon the very element that the women so longingly call forth: they lure the interloper into the water and drown him.

In some versions of tales about them, the rusalki are portrayed as shape-shifters, most frequently appearing as unearthly and beautiful young women, but also as birds, particularly water birds such as swans or ducks. This aspect of their nature as a mixture of animal and human relates them to other female water-beings found throughout mythology and folklore around the world, from the sirens that tempted sailors to their doom in the Odyssey to the mermaids that continue to appear in popular modern films and literature. Joanna Hubbs, who has traced the lineage of the rusalki in her book Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture, views them as the descendants of an earlier Slavic water elemental, a character part woman and part beast, “the beregina, [which] assumed in folk art the form of the half-woman and half-bird or fish-siren.”1 Hubbs states that the name of the rusalki’s ancestor finds its source in the word “bereg,” which may be translated as “shore.” Until the gradual modernization of village life, beginning after the Russian Revolution in the early twentieth century, the rusalki were invoked annually as harbingers of spring. A week of ceremonies and celebrations called the Rusaliia took place in many areas throughout northern central Europe. It began seven weeks after Easter, a date marked in the Christian calendar as Whitsun or Pentecost, and consisted of rituals, music, and dancing. In some areas, such as Serbia, the women dancers were prone to fall into trance states, during which they would prophesy. Central to the ritual was the selection of a birch tree that the women would decorate with ribbons and linen cloths embroidered with ancient goddess imagery. Specific songs were sung as the birch was cut down and brought from the forest into the village, where it served as a focus for the ceremonies. While some of the songs and dances were playful, the most critical function of the week was the invocation of the rusalki.

Based on anecdotal reports of conversations with elders who still remembered witnessing or taking part in the Rusaliia, it is possible to imagine the scene. A young woman walks to the highest point of the village and faces the vast forests that lie beyond her cultivated world. She is dressed in her finest clothing, replete with embroidered symbols of animals, birds, and a central motif of a stylized goddess figure in the form of a tree, the Tree of Life. She stands and sings in haunting tones, begging, urging, and enticing the water spirits to leave their wild forest world and return to the fields and gardens, bringing the gift of fertilizing rain and dew. When she tires, another woman steps up and continues the call.

With the conclusion of Rusaliia week, a sacrifice was often thrown into the nearby river, either the decorated birch tree or a female figure shaped out of vegetation and dressed in women’s clothing. In some villages, the tree was torn to pieces and scattered around the fields to increase the harvest yield, or its branches were brought into homes for good luck. These ceremonies varied widely across Russia, Ukraine, and other Central European countries, but the invocation of the female water spirits remained the primary intent, and the rituals were always carried out by women.

From earliest times and throughout much of human mythology, the element of water has been viewed as feminine. Beginning with the first stories written down in Mesopotamia six thousand years ago, the primal waters were portrayed as goddesses. To the Sumerians, she was Nammu and later Tiamat, from whose body all of earthly creation was formed. Many of the major rivers of Europe and Asia are given the names of female deities. In The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols, Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant have examined the symbolism of water across cultures, and determined that there are three principal meanings: “It is a source of life, a vehicle of cleansing, and a centre of regeneration.”2 All of these characteristics may be seen in the multiple aspects of the rusalki, as they return each spring to bring regeneration to the fields and orchards of the villagers, and to cleanse away the remnants of winter. Even their aspect as avenging figures may be viewed in this light, as a cleansing of a cultural shame—the betrayal of a young girl’s innocence—though impersonally directed. We humans begin life in water and are washed into this world on an amniotic wave. Little wonder, then, that water enchants us and is inextricably linked to the miracle of fertility and birth. Moving or still, it sustains all life yet also contains in its very nature the ability to extinguish the breath of life as easily as it can extinguish a flame. Perhaps it is this dual nature that gives elemental beings like the rusalki such a seemingly unresolvable balance of opposite powers: to give, but also to take away, life.

Down through the centuries, these figures have attracted a rich accretion of folklore, reflecting the cultures in which they are honored. The implacable anger of the rusalki towards men is explained by the nature of their origins. They are viewed as the unquiet spirits of young women who died unjustly, perhaps jilted—or even murdered—by a lover, or who committed suicide after his betrayal, sometimes dying in unmarried childbirth or as a result of maltreatment by a male power figure. This retributive nature may also be related to a myth associated with Artemis, the Greek goddess and guardian of the forests, who was said to have punished the hunter Actaeon when he unwittingly came across her bathing in the woods with her nymphs. Transfixed by her beauty, he couldn’t look away, breaking the taboo against any man invading her sacred precincts. Artemis turned him into a stag, and his own hunting hounds, who could not recognize their master in this animal state, tore him to pieces. The tale is a warning to men who dare to trespass into the world of women’s mysteries. To modern eyes, Artemis’s punishment of Actaeon may seem arbitrary and extreme, likewise the rusalki’s treatment of unwary men who fell under their enchantment. But Artemis was more than the guardian of the forests and animals. She was also the goddess of children from about the age of nine until they assumed adulthood, and young girls were particularly under her protection. It was to her temple and her priestesses that parents took their daughters, in early adolescence, to experience the joy of being a child one last time before entering into the responsibilities of adulthood and marriage. Safe from any unwanted interference, the girls were encouraged to engage in athletic events, to hunt and swim, to run wild in the woods, and to take part in rituals dressed in furs and called “little bears.” For a male to enter these precincts would have been sacrilege, and he would have been dealt with severely. Should he harm one of the children in Artemis’s care, he would risk the ultimate punishment. The early Greeks understood retribution well. It is, after all, at the core of some of their finest dramas. To evoke the anger of a god was the most dangerous act a mortal could perform, and brought on a curse that sometimes lasted generations. In the harsh lands of northern Europe, the unnecessary death of a young woman had the potential to disrupt not only family life, but the balance of the community as well. On an archetypal level, such an act defiled the natural cycle of fertility and birth that was essential to the health and future of the village. The rusalki’s revenge indicates how seriously such behavior was regarded.

The figures of Artemis and the rusalka (singular for the plural rusalki) were already thematically related through their associations with maidenhood and with the forests and their lakes and ponds. Such a syncretistic blending of characters and themes is common to areas where multiple cultures have come into contact. Mythology is fluid, flowing from one place to another as quickly as a storyteller can move from one town to the next. Central Europe experienced many waves of invaders, traders, and conquerors, all of whom brought stories from Asian, Mediterranean, and even Nordic countries. Joanna Hubbs draws comparisons between the maiden rusalki’s associations with spring and the Greek mystery religion of Demeter (the personification of the cultivated Earth) and her daughter Persephone, particularly the aspect of the young maiden’s return to her mother, which brings about the rebirth of the agricultural year.3 It is also possible to view the rusalki’s vendetta against men as a psychological compensation, giving power to the powerless through the agency of myth. As the earlier matrilineal customs of old Russia dwindled and the tsar’s masculine model of governance superseded them, the status of women shifted and worsened. When a voice is unjustly silenced, it will seek an alternative outlet. Much of folklore and folksong fills this need: righting a wrong, demanding justice, telling in metaphor a truth that may not otherwise be spoken, seeking—as water seeks—an ultimate balance. The helpless anger of women denied their power becomes an undercurrent that rises to the surface of the culture through their stories.

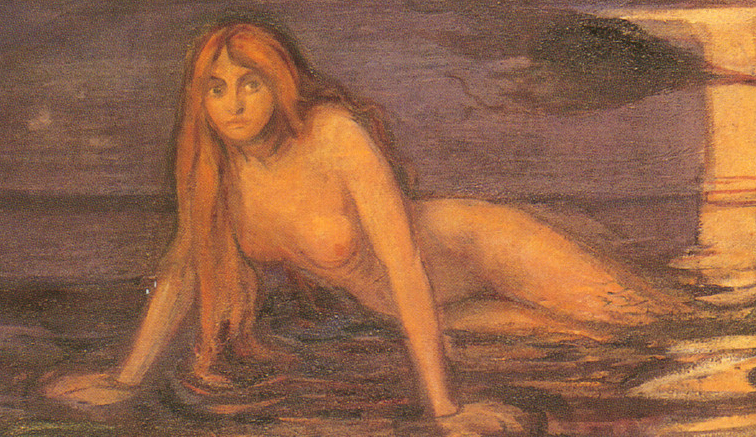

During the Romantic Period of the arts in Western Europe, beginning in the late 1700s and continuing through the early Victorian era, the character of the rusalka was reinterpreted yet again, this time by the educated artistic elite of the literary and musical spheres. The Romantics longed for an Edenic natural world and were reacting to what they saw as the dehumanization of both the people and the landscape through advancing indus-trialization. An idealization of rural and village life led some authors and com-posers to old folktales and songs for inspiration. The story of a beautiful young girl meeting a tragic end, yet doomed to remain earthbound rather than finding an afterlife in heaven, held vast appeal. She now took on the role of the perfect romantic figure, but in their stories she would be cast as the heroine rather than the vengeful villainess. Just as the Romantics longed for an emotional, personal relationship with the natural world, the rusalka would be personalized as a feminine embodiment of their soul mate, Nature. In their operas, poems, lieder, ballets, and art, she would be sin-gled out, represented as the only one among her heartless sisters to fall in love with the young man who stumbles into her forest glade. While there are a few happy endings, the denouement of these works tends to play off the trope of the beautiful rusalka sacrificing herself to save his life; or, if she is forced by an evil fate to fulfill her role, she is shown griev-ing forever, weeping and mourning her regret. From this particular branch of the Romantic era come such works as Sir Walter Scott’s tale of the Melusine (1802), a French creature half-woman, half-serpent, who dwelt in a spring; de la Motte Fouqué’s “Undine” (1811); Heinrich Heine’s “Lorelei” (1838); Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” (1836); and Tchaikovsky’s ballet “Swan Lake” (1876), among many others, up into the twentieth century when Dvorak’s opera The Rusalka (1901) made its way onto the stage, haunting all listeners with the lonely, lovesick rusalka’s unforgettable song to the moon.

As water assumes the shape of its container, so this ancient figure reshapes herself into multiple forms, reflecting the time, the place, the needs and longings of those who tell her story. The language or the locale may change, but always at the heart is the never-ending cycle of life and death, played out in the untamed, enigmatic waters of the forest’s secret places. ♦

I am also grateful to Dr. Barbara E. Wolf, for her insightful comments and conversation on this topic.

1 Joanna Hubbs, Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), p. 31.

2 Jean Chevalier, Alain Gheerbrant, The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols. Trans. By John Buchanan-Brown. (Penguin Books: London, 1996), p. 1081.

3 Hubbs, p. 53.

From Parabola Volume 34, No. 2, “Water,” Summer 2009. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.