Hélène Fleury and a group of co-workers, the Association Archéologique Kergal, have made a study in depth of the European megalithic sites, especially in Brittany. They have published a report of their findings called “Le Tumulus de Gavr’inis,” and other papers are forthcoming. The following has been translated and much condensed from a paper called “Sacred Space in the Megalithic Monuments.” Much of the supporting data has been omitted due to limitations of space.

The megalithic phenomenon appeared on the earth suddenly. For several centuries, beginning in the fourth millennium before Christ, in places as widely separated as Korea, Tibet, India, the Caucasus, Anatolia, Palestine, North Africa and Europe, men felt the same necessity to erect huge stones according to laws that we are trying to discover. Everywhere we observe the same type of construction; and inevitably the idea arises of a megalithic civilization—a type of culture, rather than a race or nation, a way of expression of the knowledge of the period.

The revolution brought about by carbon 14 has already obliged us to accept that the Atlantic megaliths predated the great civilizations of the Middle East such as Pharaonic Egypt. “Ancient Europe is older than we thought,” says Colin Renfrew; shall we some day have to submit to the evidence that “ancient sciences are older than we thought”?

According to the archaeological data, it would seem that about nine thousand years ago, starting from an eastern origin in the Caucasus, agriculture appeared, was slowly propagated and finally reached the Western countries. With an inverse movement and starting from a western point of departure in Armorica (roughly corresponding to modern-day Brittany) about seven thousand years ago, the megaliths, oldest constructions made by the hand of man, appeared and spread eastward in the same way. These two contrary movements, meeting and blending about 4000 B.C., gave rise during the Neolithic period to a great civilization which was characterized by the beginnings of agriculture. This civilization, considered under its architectural aspect, is called the megalithic.

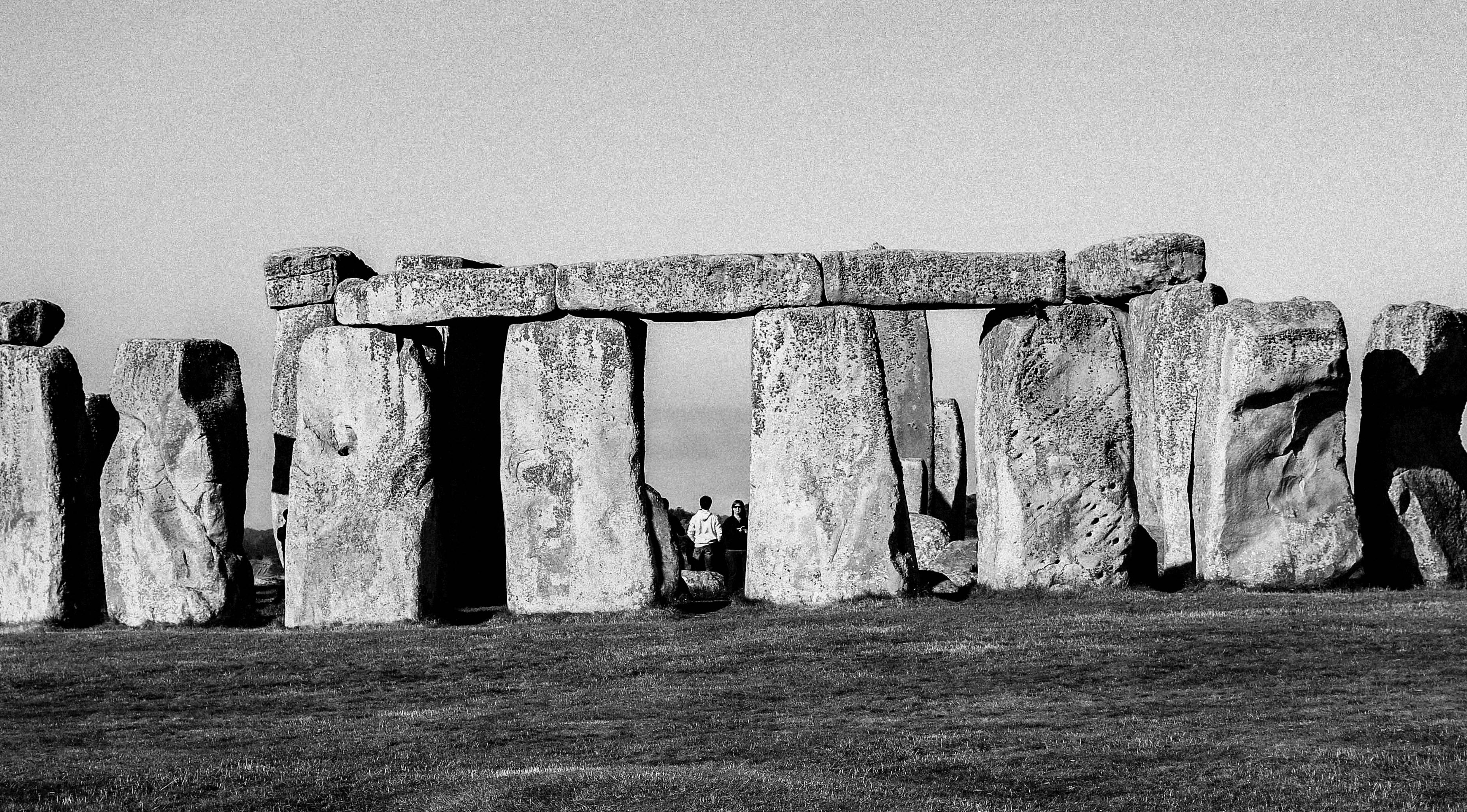

This was the era of the great stone monuments such as Glastonbury, Stonehenge and Avebury in England; and of New Grange in Ireland and Gavr’inis in Brittany which have been the special objects of our study.

In the space enclosed by these monuments, what was inscribed on the ground was the analogy of man with the cosmos (Greek kosmos signifies at the same time world and order); the whole earth and the universe, considered in their reciprocal movement, were taken as fundamental symbols in the ancient sciences. In mythic language, we could speak of the earth as a gigantic living creature, the prototype of Man in all his possibilities. The monuments, all built around a center point, show the earth traversed by the axis of its rotation, symbolizing the connection between above and below. This invisible axis which joins earth to heaven is the straight path leading to the Pole Star, which in the ancient world constituted a hole in the celestial vault: the same idea as that of an axis which, like an arrow, punctures the heart of the sky.

With the stone circles, we come at once to the idea of megalithic sacred space. The circles, marked by an arrangement of roughly dressed stones, give the uninformed visitor the impression of something unfinished, crude, without any real structure. However, the studies that have been made both in France and in Great Britain have revealed remarkably accurate geometric and astronomical features, which imply a construction based on a rigorous pattern. We find identical features in the temples of later civilizations.

The simplest stone circles are bounded by a line of menhirs, either joined together or with spaces between; but in other cases we find more complex monuments in which several concentric constructions are combined to form true temples. One type of sacred place is well represented by the gigantic natural site of Glastonbury, in Somerset. The monument was set up in the Neolithic period to represent on the ground the signs of a great zodiac. This zodiac, 16 kilometers across, can only be seen from above. From the level of the ground, nothing at all is distinguishable.

Many other examples can be found in Brittany. Like many spiritual centers, the mound of Gavr’inis, the highest point of a small island in the middle of the Gulf of Morbihan, has to be sought; it passes unnoticed by the casual traveler. But from the first steps on the path that leads to the depths of the sanctuary the impression is so strong that it calls for a deeper study. One is astonished by the magnificent sculptures that almost completely line the inner walls of the entrance gallery to the central chamber, which gave Gavr’inis its reputation of being the world’s most beautiful dolmen.

In the plan of the dolmen, four parts appear rather clearly: the central chamber and an access passage divided in three. The journey from the entrance to the building’s central point seems to correspond symbolically to the ascent toward the center of oneself, the summit of the “natural” mountain of man where he enters into contact with his “celestial” nature, according to the symbolism of the polar mountain.

We can’t linger here over the sculptural symbolism; we can only say that almost all the signs engraved on megalithic monuments are found again in this place: the spiral, the axe, the serpent, the cross, etc.; and even more frequently, concentric half-circles, sometimes turned toward the sky, sometimes toward the earth. All these shapes connect with each other in a curious movement which beckons the visitor along the passageway to the culmination of the inner chamber. The homogeneity of these carvings marks them as the work of a close-knit team; it is as if one hand alone had engraved on stone after stone the process of one sole journey. This impression of unity is reinforced by an architectural study of the whole mound, both in vertical cross-section and on the horizontal plane.

It seems that the essential concern of the priest-sages of traditional societies has always been to express the inexpressible, to make perceptible the vital movement which animates all living things from within—in order to help men to understand better the meaning of their lives, and to safeguard mankind’s patrimony of real knowledge. The study of what remains to bear witness to the existence of sacred places makes it clear that the method used for the transmission of this knowledge was sacred art, and we can well imagine that such a task required enormous efforts on the part of those who had to pass it on as well as of those who attempted to understand it. Our modern education has taught us very little about the idea of sacred art. It certainly seems that what we call “art” has few points in common with this “exact science” which demands a more total participation of the whole being.

Sacred art is the science of forms. Forms express the coincidence between profane sciences and techniques and the religious sciences; that is, they link physics and metaphysics. These forms are determined by precise laws which are the same for the building of a temple, the making of a vase, or the creation of tools for crafts. Sacred art uses symbolic language and mythical thought as a means of expression; so if we wish to understand its message we have to reinforce our ordinary way of understanding with a more informed feeling and an intuitive perception whose “light” can resolve the dilemma of our habitual discursive duality. In other words, it certainly seems that the knowledge transmitted by these priest-sages of the ancient world was that of the unity of all things. This knowledge could only be transmitted or assimilated by people for whom inner unity was an actual experience or for whom this experience was the goal.

In the same way, we can foresee perhaps that the preparation for this state of symbiosis of knower and known could only be the result of a true culture, that is of a traditional culture such as must have been “organized” among the neolithic peoples. Later the great civilizations like that of Pharaonic Egypt transmitted the same teachings and explained that this knowledge has to be acquired from a Master or in the heart of a school. The teaching of Pythagoras is a good example because of certain affinities, which become clear on further study, between that school and the megalithic tradition, although the latter preceded the former by several millennia.

Whatever the period, whatever the construction sites, these buildings remind us of the existence of organized societies in which each member participated in a collective work—a work which required from each one that he should “bring his stone,” an act which, being timeless, defies the passage of time.♦

Abridged from the original in Parabola Volume 3, No. 1, “Sacred Space,” Spring 1978. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.