Although love has existed as long as the human race itself, it was Jesus Christ who posited this mysterious force as being at the center of experience. The Law of Moses told the Jews to “love the Lord thy God with all thy heart and all thy soul and all thy mind” and to “love thy neighbor as thyself,”1 but it was Christ who chose these as the two greatest commandments.

I am not saying that this emphasis on love makes Christianity superior to other religions. It’s rather that we in the West extol love because we consciously or unconsciously remain Christians, no matter what box we may check under “religion” on the census form. Does love deserve to stand on the pinnacle of veneration? Since it is Christianity that makes this claim, it is to Christianity that we will turn for the answer.

One commonly overlooked motif in the Gospels is money. It’s hard to think of any other sacred text that is more thoroughly pervaded with monetary images. People are given talents—sums that in those days were as remote and inconceivable as a billion dollars is to most of us today—and they are paid wages, lose and find coins, and accrue debts. The central prayer of Christianity includes the request “Forgive us our debts as we have forgiven our debtors” (it is “debts” and not “trespasses”; the word in the original is opheleimata, which comes from opheilo, “to owe,” and Liddell and Scott’s Greek lexicon, the standard work in English, does not even give “trespasses” as an alternate meaning.2

The Lord’s Prayer, then, asks for forgiveness of debts rather than forgiveness of sins. The difference is great. A debt involves a transaction, an exchange in which a cost is incurred. We discharge debts by our good deeds; we incur them when others bestow kindnesses on us. Favors and obligations are as much a part of our currency as the money supply. They are not reckoned on the ledgers of the Federal Reserve, but they are calculated with an equal rigor in our minds and hearts. And most of these exchanges involve no legal or even moral obligations. You may owe someone a Christmas card, but it’s not a sin if you fail to send it.

It is possible that when Christ uses the language of money, he is thinking of this network of obligations, which extends far past transactions in conventional currency. He urges his disciples not to avoid these debts but to pay them fully and more than fully: “If any man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloke also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain” (Matt. 5:40–41). On my office wall I have a framed page from the Tao Te Ching that expresses the idea succinctly:

After a bitter quarrel, some resentment must remain.

What can one do about it?

Therefore the sage keeps his half of the bargain

But does not exact his due.

A man of Virtue performs his part,

But a man without Virtue requires others to fulfill their obligations.

The Tao of heaven is impartial.

It stays with good men all the time.3

In early Christianity, the kind of love that goes past these debits and credits was known as agape, which Paul praises in a famous passage. Agape “suffereth long, and is kind; …envieth not; …vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own” (1 Cor. 13:4-5). But agape itself is not always what we take it to be. Liddell and Scott’s Greek lexicon says that the word can imply “regard rather than affection.”4 And in fact the general usage of this word in ancient Greek suggests something slightly remote and disinterested.

The twentieth-century Russian theologian Pavel Florensky contends that pure agape has a chilly air about it: “In the common usage of the [Greek] verbs of love, agapan is the weakest and is close in meaning to such verbs as to value, to respect. And the greater the place occupied by the rational mind, the smaller will be the place is occupied by feeling. Then, agapan can even mean to ‘value rightly, not to overvalue’.”5 (Agapan is the infinitive form of the verb from which agape is derived.) I’ve often wondered how the New Testament would read if agape were translated as “respect.” “Respect thy neighbor as thyself.” “Respect one another, even as I have respected you.” I believe it would be no further, and quite possibly closer, to the original meaning than the usual translations of “love” and “charity.”

We can go a step further and ask whether even agape itself is entirely free from commerce. Christ tells his followers: “When thou makest a dinner or a supper, call not thy friends, nor thy brethren, neither thy kinsmen, nor thy rich neighbours; lest they also bid thee again, and a recompence be made thee. But when thou makest a feast, call the poor, the maimed, the lame, the blind: And thou shalt be blessed; for they cannot recompense thee: for thou shalt be recompensed at the resurrection of the just” (Luke 14:12–14).

There is certainly something sublime in this charge, which frees us from the tiresome expectation of reward. Or does it? Looking closer, we see that Christ’s command does not abolish the transactions but merely transfers them to another level. Our credits will be recorded not in the minds and hearts of our neighbors but in the ledger books of heaven. Perhaps this is an improvement over the give-and-take of ordinary human interchanges, but it can present a spiritual trap in its own right. The twentieth-century Russian philosopher Nicolas Berdyaev observes that in Christianity,

Love for men, for neighbors, friends and brothers in spirit, is either denied or interpreted as an ascetic or philanthropic exercise useful for the salvation of one’s soul. Personal love for man and for any creature is regarded as positively dangerous for salvation and as leading one away from the love of God. One must harden one’s heart against the creature and love God alone. This is why Christians have often been so hard, so cold hearted and unfeeling in the name of virtues useful for their salvation. Love in Christianity became rhetorical, conventional and hypocritical. There was no human warmth in it.6

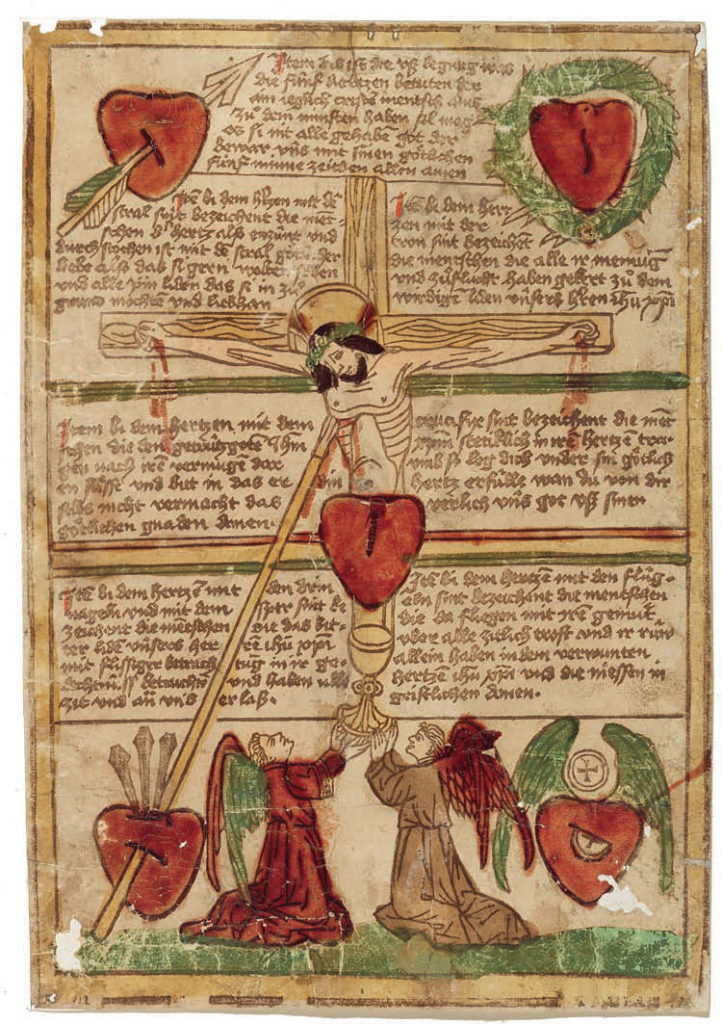

In speaking of this kind of love as an “exercise useful for the salvation of one’s soul,” Berdyaev reminds us that transactionality is not so easy to avoid. Even when it inspires acts that are apparently selfless, the motive of buying favor with God (or avoiding punishment from him) may be hiding under the surface. The love of would-be saints often has a whiff of hypocrisy; they seem to be obeying Christ’s injunction to lay up treasures in heaven as if they were making deposits in a bank. Berdyaev adds, “Ordinary sympathy and compassion is more gracious and more like love than this theological virtue.” An earlier Russian philosopher of love, Vladimir Solovyov, expresses the same sentiment: “This unfortunate spiritual love reminds one of the little angels in old paintings, which have only a head, then wings and nothing more.”7 Divorced from the more worldly but more engaged transactional love, agape dries up into a stiff theological virtue.

However much it may be praised, it’s hard to see how agape could totally eradicate our urges for human closeness and companionship and sexuality. Ultimately we are joined to one another by our transactions as much as by anything else, and no degree of sanctity is likely to change this fact. For most of us, probably even the best of us, love involves an intense, even violent dynamic between a sublime impartiality and the sizable part of our nature that keeps a watchful eye out for its own interests. It is our very humanity that spans this whole range of feeling, and if we despise and revile one section of it, we risk making ourselves not more but less human.

What, then, is love? Here is one answer: love is that which unites self and other. This is as simple and naked a characterization as I can imagine, but even so one refinement may be needed. After all, the lion loves the lamb so much that it wants to make the lamb one with itself. Perhaps, then, we should add this modification: Love is that which unites self and other while maintaining the integrity of each. The moment of ecstatic union of lover and beloved, whether shared in a moment of sexual ecstasy or of emotional understanding, is just that — a moment. The boundaries between the two are relaxed but not erased. It may be love in this sense that sustains the universe, preserving all things both from the annihilation of assimilation and from the death that lies in total separateness. ♦

Notes

1 Biblical quotations are taken from the King James Version.

2 Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, ed. Henry Stuart Jones (Oxford: Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1968), s.v. ofeilhma (opheilema). “As we have forgiven” is also a more correct rendering of the verb tense than the conventional “as we forgive.”

3 Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English, Tao Te Ching (New York: Vintage, 1972), §79.

4 Liddell and Scott, s.v. agapaw (agapao). This is the verb from which agape is derived.

5 Pavel Florensky, The Pillar and Ground of Truth: An Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters, trans. Boris Jakim (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 287.

6 Nicolas Berdyaev, The Destiny of Man, trans. Natalie Duddington (New York: Harper & Row, 1960), 188.

7 Vladimir Solovyov, The Meaning of Love, trans. Thomas R. Beyer Jr. and Jane Marshall (Hudson, N.Y.: Lindisfarne, 1995), 82.

From Parabola Volume 35, No. 1, “Love,” Spring 2010. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.