A miller, a beautiful daughter, and a creature named….

Once a poor miller was summoned to meet with a king. The summons alone must have filled him with terror. Evolutionary biologists tell us that we are wired to link survival with acceptance by the tribe. And this king was the absolute ruler of the miller’s tribe, holding the power of exile, life, and death.

The poor miller trudged to the palace as if headed to his execution. The king surprised him by asking about his family, probably congratulating himself on his noble kindness and expansiveness, to ask such a personal question of a subject who could not speak unless bidden. Startled and desperately eager to please and to be deemed acceptable, so it seemed even to the miller as he spoke, he answered that he had a beautiful daughter with golden hair. But this sparked not one flicker of interest in those cold, royal eyes. The miller saw that his precious daughter, his treasure, meant nothing to the king. She was just another pretty woman to a man surrounded by pretty women, no one special, an object really, easily replaceable.

The miller blurted that his beautiful, golden-haired daughter could spin straw into gold. The Brothers Grimm reported that he made this wild claim to seem important, and this is true. But the roots went deep. The miller knew that he himself was no one in the eyes of the king, just a minor problem to be solved, an impediment to the flow of tax revenue into the royal coffers. But his daughter was special. The miller’s love for her was sacred in the deep sense of set apart from the muck and disappointment of his life. He saw how unique she was in this world, how good and beautiful. He wanted this king to appreciate the marvel of her existence, and he knew this king loved gold.

We can only imagine how the poor miller felt after he spoke. He had betrayed what he most deeply loved and understood to be true. He loved his work and he loved his daughter. Milling grain is one of the most ancient human occupations. Even hunter-gatherer societies had millers. It is hard, humble work but it is wholesome, even holy. The miller helped feed people, grinding the grain for their daily bread. How he wished that he stood before the king calm in the knowledge that it was good to be a miller, even noble in the root sense of taking care of kin, but at least good enough. Yet it was worse. He had forgotten that it was good enough to be a father of a daughter, and that she was enough, magic enough, just as she was.

Now it was too late. “This is a skill that would serve me well,” said the king. “Bring your daughter to the castle in the morning, and I will put her to the test.” He didn’t have to warn the miller that hiding such a treasure would lead to death for them both. The miller didn’t sleep that night. The next morning, he brought his daughter to the palace. Sorrowfully, apologetically, he tried to explain what had happened but he soon faltered. He could find no explanation beyond his inner smallness, no context beyond a fear-driven reaction. He had betrayed his beloved daughter, betrayed a love he held sacred. He remembered holding her when she was a baby. He watched the guards lead her away into a royal dungeon piled high with straw.

The king swept into the cell. The miller’s daughter was pretty, he observed. Her blond hair and tawny skin glowed and her clear blue gray eyes looked out at the world with forthright innocence and bright intelligence. But this was not the point. He gestured to the wheel and spindle set up in the center of the room. “Let’s see if your father tells the truth,” he said. “Spin this straw into gold by dawn tomorrow or you die.”

Most of us know the version of the story told by the Brothers Grimm, who collected it in Germany in 1812. But other versions of this tale stretch back four thousand years, and many of us have spoken of spinning straw into gold. Most humans know how it feels to be in this impossible situation, desperate to spin something shiny, gold, full of the doomed sense that we must do something incredible, must do more and be more than we really are.

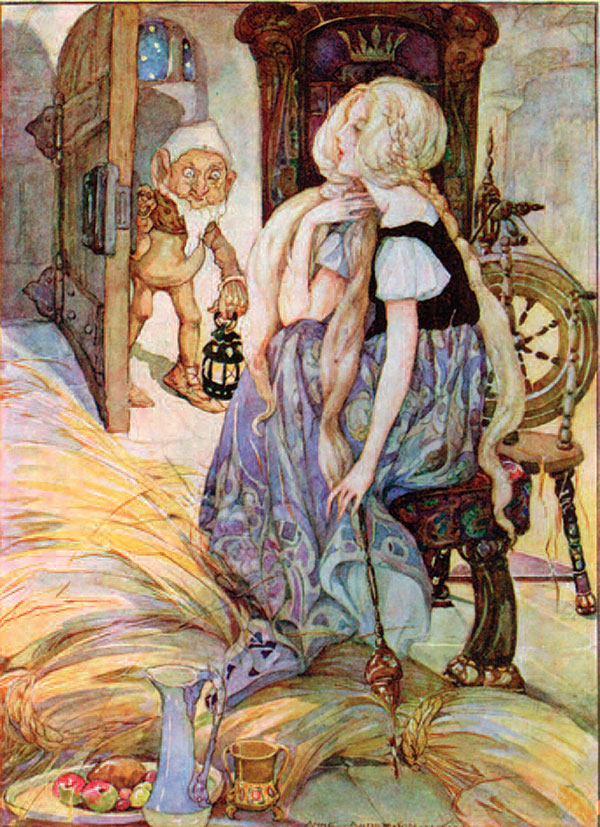

The miller’s daughter sat alone in her cell, plucked from an ordinary life that now seemed impossibly happy. She could think of no way out. She began to weep, abandoning herself to bottomless sorrow and fear. Finally, as her crying subsided, a door opened and a strange little man appeared.

“Good evening fair maiden,” he said. “Why do you weep so bitterly?”

He smiled, tipping his head and looking at her quizzically. Although he was tiny, he looked almost handsome, pale with an aquiline nose. But he did not meet her gaze for long. A nervous tic pulled his smile into a wincing grimace and his eyes blinked rapidly. He seemed to be calculating very rapidly. Who was he? Where did he come from and what did he want? In ordinary conditions, she might have asked such questions. But her life was on the line.

“I’m supposed to spin all this straw into gold by morning or I’m dead,” she said. “I have no clue what to do.”

“What will you give me if I spin it?” He smiled, as if this was a joke, as if he were far too kind to take advantage of her. But the smile became a wince. She immediately took off her necklace and offered it to him. No, no, he said softly, holding up pale hands with long, thin fingers. His way of speaking and his gestures were overly careful, as if he were walking on ice. She held out the necklace, insisting, and his pale hand darted out quickly and snatched it, a lizard capturing a fly.

He sat down at the huge spinning wheel, turning his back to her. Fishing a notebook and pen out of his worn jacket, he made feverish calculations. He rubbed his forehead, studied what he wrote, blinked rapidly. Whir, whir, whir, the wheel spun round. For a long time nothing happened, then the spindle glinted with threads of gold. Amazed, the miller’s daughter asked him what he was doing. He shrugged his sharp, thin shoulders and mumbled that it was science, not magic. What kind of science, she wanted to know. She wanted to talk with him, to know him, but a cold, detached look warned her away.

The strange little man spun all night until all the straw was gone. The faint smell of sun and earth that came in with the straw was also gone, and the cell grew damp and cold. The first rays of sunlight struck piles of golden string. The miller’s daughter leaned closer to see the last of his work. She rested her hand on his shoulder.

Startled, he looked up into her eyes and felt a surge of joy. He saw himself reflected there in sparkling points of light. After a lifetime in the shadows, invisible to everyone in the palace, tolerated only for his skill at calculation (and they asked such silly questions; they had no idea what he could do), he was seen. He existed. A beautiful woman thought that he was marvelous. Bowing deeply, happy, he slipped away.

The king was delighted with the gold, but this only fueled his greed. The miller’s daughter was led into a larger cell with an even bigger pile of straw. Again, she was commanded to spin all of it into gold by dawn or be killed. Again, she despaired and wept, and again the door opened and the little man appeared.

“How did you know?”

He shrugged and smiled his wincing smile. “I know this king.”

She took the ring from her hand and offered it to him. “My mother’s ring,” she said. He waved it off, but again his hand darted out and took it from her. He tucked it into his pocket, turned his back on her and sat down the wheel. The deference and smiles were gone. He checked his calculations and bent to his task. Straw went in and gold spooled out. “How did you learn this magic?” His body cringed from the question. “There is no such thing as magic,” he said. “Magic is what people call science because they can’t do the math.”

For a flash, she saw his real deformity, what kept him from love. It wasn’t his tiny size but the way his mind, his math, held himself apart from life. She asked him what his science taught him about how to live. He looked up and studied her, eyes narrowed. “When you do the math and learn the vastness of the cosmos, you have no patience for anyone who insists they are special in any way.”

How self-enclosed he seemed to her, cringing away from her as he spoke. “Have you ever been afraid that you might die?” she asked. He smile froze on his face. His curse was to go living on and on without really living. “Suddenly you see that everything is special, every moment.”

By first light, the room was full of gold and the little man was gone. The greedy king was overjoyed. She was not surprised when he led her into a still larger cell full of even more straw. “I know,” she said. “I must spin all to gold or…”

“And you will be my bride,” the king said as if he were giving her the greatest gift of all.

“I have nothing left to give you,” she later said to the little man. By now, she saw how bitter and full of rage he was, how full of calculations and dreams and empty of life. She herself had neither magic nor math. She was nothing but herself, as plain as straw.

“Give me your first-born child if you become queen,” the little man said quickly. Was he serious? The miller’s daughter saw the hatred and grasping in his eyes. She felt a surge of anger. She had asked for none of this, not her father’s damning praise, not the king’s imprisonment, nor marriage to that tyrant who was willing to see her dead. She said yes to the horrible little man’s outrageous demand. None of this was her choice, none of it felt real.

The little man bent to his work. He looked very old to her, and yet as wizened and otherworldly as a newborn. He had lived a long time but only in his mind. She shivered to think of it. The hours passed in silence; the wheel turned; the smell of earth and sun ebbed away as straw became gleaming coils of gold. At last, the little man stood. He knew the miller’s daughter would marry the king. His face was pale. His smile was a wince. He despised her. She was just like all the others he had loved and helped. They always left in the end. “Don’t forget your promise,” he said and slipped away.

The king kept his vow. Their marriage was a fairytale in the grimmest sense, lavishly beautiful and dark. But then a child came and she discovered a love that was pure and unbounded. She took the baby in her arms and showed it life, trees, sky, dogs and cats. She took him out to the stables to see the horses. Holding her baby in her arms, breathing in the smell of sun-warmed hay, she felt a joy and ease she had never known. She felt as if she were a strand in the greater web of life.

Yet one day the little man reappeared. Desperate to save her son, the young queen offered him riches, anything else in the kingdom. He shook his head no. “Something alive is dearer to me than all the wealth in the world.” She knew he would say this. He of all people knew that life was more precious than gold. She wept. He felt a pang of compassion and gave her a distant chance.

“You have three days,” he said. “Find out my name and you can keep your child.” His compassion was veined with a rage to be known. He was the one who spun gold. He wanted the kingdom to know his name. All night, the queen lay awake thinking of names and of all she knew of the little man that might show her a way out. After hours of this, she went and gathered her child in her arms. The minute we try to save ourselves we are lost, she realized. Spinning thoughts, we forget the living experience of the present moment, forget the body and the heart that can help us remember our deepest humanity, that know the true value of being alive. She stood in the darkness of a summer night, holding her child, feeling the warmth and weight of him, smelling his sweet baby smell. The moment felt sacred, yet not at all separate from ordinary life. She was no one, just a pair of arms, a witnessing consciousness. She was nameless, any mother who had ever lived holding her child in the middle of the night. And yet as humble as this embrace was, she felt that by enacting it she was taking her place in a line of mothers stretching back to the first mother. She was a human being. She felt as if she were taking her place in a great mystery.

The next morning, she summoned a messenger she could trust. Tall and calm, he seemed a very different helper than the nervous little spinner. He was there to listen and observe. The messenger set out and searched the kingdom, asking people about curious creatures with curious names. He visited cafes and marketplaces; he listened to people talking in the streets. He listened to everyone without judgment. On the morning of the third day, the messenger returned.

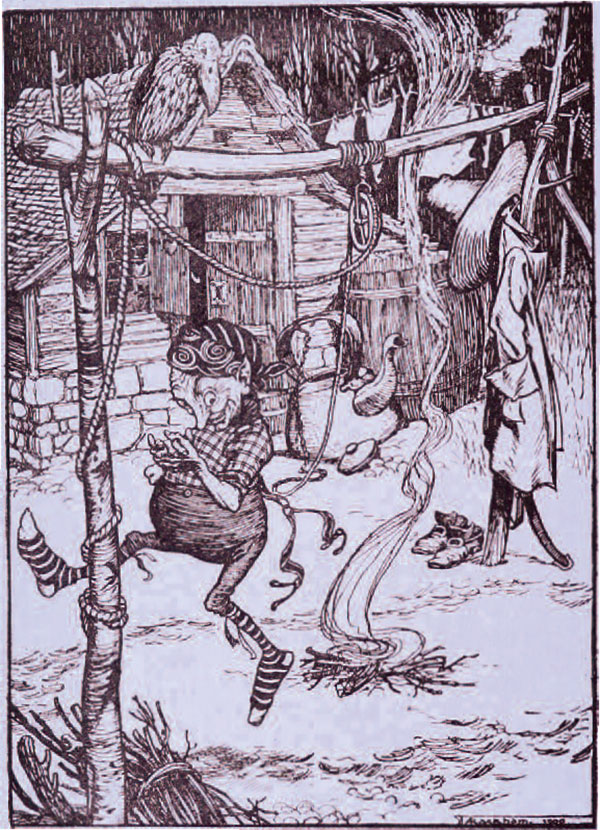

“Near the edge of a distant forest, I saw a little hut,” he told her. “Outside the door before a roaring cooking fire, there was a wiry little man dancing and singing with wild abandon. ‘Today I brew and tomorrow I bake,’ he sang. ‘Tomorrow the queen’s child I’ll take.’ The little man cackled and stirred the pot. ‘How sad that nobody will ever know that my name is Rumpelstiltskin.’”

Of course, thought the queen. The name literally means “little rattle stilt,” a poltergeist or spirit that rattles the ridgepole of a house. It stands for the rage to knock the dishes off the shelves, to shock and awe, to be somebody special. The queen remembered her father’s boast, her imprisonment, the desperate spinning, then her holding her baby in her arms. In this moment, she remembered who she really was.

She knew his name.

She saw how desperate he was to be known, to plant his flag, to make his mark. Yet being fully alive, she saw, took a kind of surrender. We must agree to take our place in life, to be what we actually are, body, heart, and mind. We must dare to be straw.

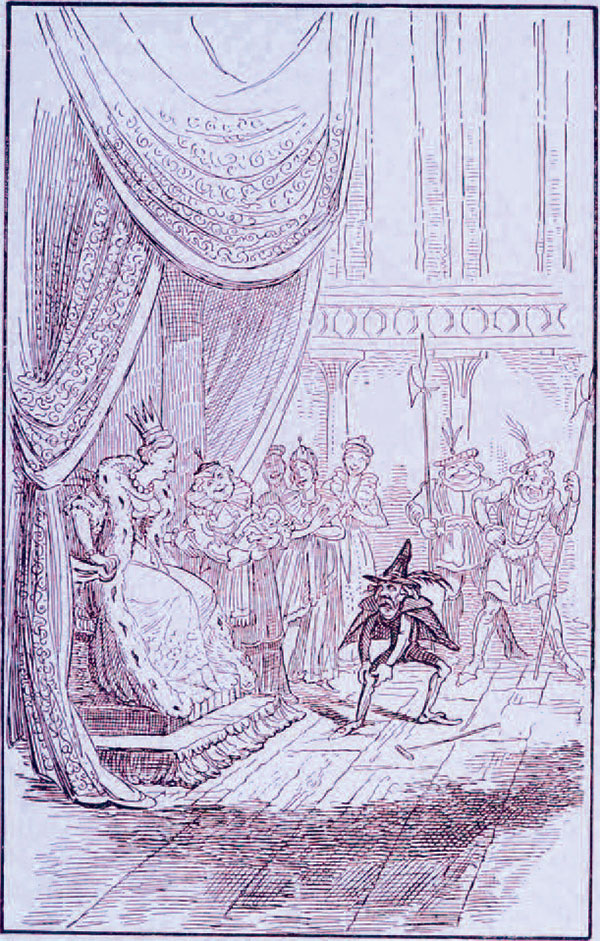

She would speak the truth. She would speak his name and let the whole kingdom know who spun the gold. She felt her feet on the earth and the warmth of the sun, felt her love for her son and freedom from all fear. He cocked his head expectantly, eyes blinking.

“Are you…Rumpelstiltskin?”

For a beat, the little man was silent. “A witch told you!” he screamed. He stamped his foot so hard that it sank into the earth. He pulled it with the full force of his rage, splitting himself in two. This didn’t feel strange but almost reassuring, a terrible confirmation. He had always felt divided, trapped in his head, cut off from life. Howling, he pulled himself together and limped off, vowing to find someone better than a miller’s daughter.

She watched, marveling that he had never asked her for her name, or the name of the son he wanted for his own. She was the miller’s daughter, and now a queen. She smiled. She knew that ultimately she was no one, anyone, and part of everything. ♦

From Parabola Volume 42, No. 3, “The Sacred,” Fall 2017. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.