The Legendary Monk Xiao Yao

Sometime around the year 1889, a baby boy was born to a poor family in a small, long-forgotten village in southern China. The facts surrounding his early years remain vague. Both his parents died while he was still a child, and the orphaned boy was entrusted to a duty-bound relative who couldn’t afford another mouth to feed. The boy’s future looked bleak. After some deliberation, the relative decided to present the boy to the abbot of Jiuyi Temple, a Buddhist monastery several days’ walk away. He packed a few belongings for the child and ventured warily with him into the forest. Despite gangs of bandits stalking the woodlands, the pair trekked to the base of Snow Peak Mountain safely and began their arduous ascent to the monastery.

The monastery was built high up near the summit, where it seemed to float among the clouds and snowy peaks. The serenity of the compound appealed to the individuals seeking refuge from the whirling chaos of life, and the spiritual aura of the temple it housed attracted souls looking for spiritual enlightenment and timeless wisdom. Although Jiuyi Temple was a small monastery that accommodated only a few dozen monks, it was venerated by the local villagers as a sanctuary that produced remarkable sages with extraordinary powers. Locals often hiked the treacherous five-hour trail that led to the monastery to receive a blessing or a healing.

The man and the boy now followed that trail, weaving through lush foliage and snaking up a series of vertiginous outcrops that overlooked the lowlands below. The view was both dizzying and dazzling. Finally, they arrived at the main gate. The monastery radiated an atmosphere of mystery and power. The dormitories and the dining hall formed the walled perimeter of the quadrangle. The pine trees growing in the inner courtyard softened the bricks and stones and exuded a pleasant fragrance that blended harmoniously with the sweet mountain air. The focal point of the monastery was the temple that stood in the middle of the courtyard—an elevated building made of sturdy timber with a curved roof covered by jade-green tiles.

Inside the temple was a twenty-foot-tall gold-lacquered Buddha seated cross-legged on a lotus flower, smiling peacefully past the spiraling wisps of incense that shrouded him and gazing dispassionately at the vaporous skies that flowed like a celestial river beyond the distant treetops.

The two weary travelers crossed the main gate reverently, and the man asked to speak with the abbot. He explained the orphan’s dire situation to the abbot, who agreed to take charge of the little boy. The man bid the child farewell and quickly returned to his village.

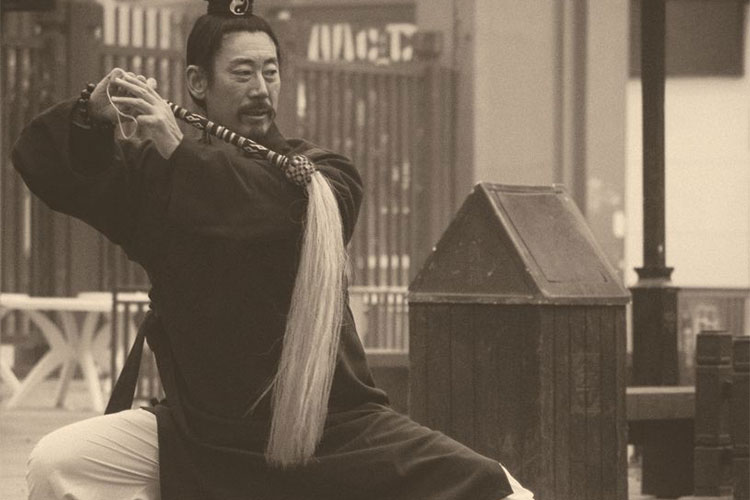

Over time, the boy adapted to his new home. The older monks became his parents and the younger monks his older brothers. He was a sprightly child with an easygoing disposition, and he was given the nickname Xiao Yao, which means “free flowing.” He learned the martial arts, healing arts, and meditation. He prayed, studied, and trained hard. When he was older, he visited other monasteries to learn special skills from other masters. For several years he lived in a cave, meditating for months without interruption. Xiao Yao mastered the most advanced practices and attained the highest levels of enlightenment.

Many years passed. Xiao Yao’s teachers died, as did the older monks who raised him. He climbed up the hierarchy and gradually became one of the senior monks at Jiuyi Temple. He was highly respected by his peers for his wisdom and was revered by the villages for his healing powers. The local mountaineers often repeated stories they heard about Xiao Yao, and his reputation became legendary.

One popular story was about an incident that took place in 1948. A cruel bandit and his gang hid out in the forest, attacking travelers and robbing farmers. On one occasion the bandit raped a young girl, and terror spread. The local authorities were too weak to subdue them, so a group of villagers sent a representative to Jiuyi Temple to plead for help. Xiao Yao was dispatched to handle the matter. No one knows for sure what happened, as Xiao Yao went into the forest alone, but the gang disbanded and some of its former members became his students….

As news of this incident and others spread throughout the county and beyond, Xiao Yao’s reputation became legendary. Streams of people ventured up Snowy Peak Mountain year round seeking his healings, blessings, and counsel.

On May 16, 1966, the Cultural Revolution was launched in China. Within a few years new policies called for the shutdown of religious institutions, and local authorities notified the monks at Jiuyi Temple that they needed to vacate the monastery so it could be converted into an administrative center. The temple was boarded up and the Golden Buddha was padlocked inside. The monks put on civilian clothes and returned to their former homes. Xiao Yao, however, had no family, so there was no village awaiting his return. Now nearly eighty years old, he had no place to go. He spent a stretch of time living in the mountains as a hermit and then decided to leave Snowy Peak Mountain. He wandered hundreds of miles east along the bank of the Xiang River until he reached Xiangtan.

Xiangtan was an industrial city with a large steel production plant that employed tens of thousands of workers. The factory had been built during the 1950s with the help of Soviet engineers. A luxury resort the locals called Yi Suo had been constructed to house the foreigners who managed the factory. After the Soviet engineers departed, Yi Suo hosted Chinese government officials. Flower gardens and sweetly scented fruit trees lined the walkways. There were a swimming pool and a restaurant that served gourmet meals. The compound was surrounded by an imposing tall brick wall that shielded it from curious onlookers.

Xiao Yao applied for a job at Yi Suo and was offered the least desirable position: boiler room attendant. A boiler room attendant is always on call. He lives in the boiler room and feeds the boilers three times a day, every day. His work is solitary, ongoing, and thankless, and the pay is very low. But despite these shortcomings, Xiao Yao accepted the job and moved in right away. He slept on a flimsy mattress in the corner opposite three fiery ovens. He cooked his own food and shoveled coal diligently an hour before each mealtime. The employees at Yi Suo were unaware of his background. They knew him simply as “Mr. Tan,” the affable, kindhearted boiler room attendant who mostly kept to himself.

My family lived across the street from Yi Suo on the first floor of a modest three-floor brick walk-up. My father was an onsite construction manager for the factory and my mother worked as a cook in the factory restaurant. I was the youngest of four children. In 1972, around the time of my eighth birthday, I began to suffer from acute chest pain. My mother took me to the hospital, where the doctor prescribed some medicine, but the pain grew worse. She brought me back to the doctor, who increased the dosage and suggested I stay home and rest for an indefinite amount of time. Although the notion of skipping school thrilled me, the reality of staying home all day alone was distressing. After the first few days my restlessness became unbearable, so I snuck out of the house while my mother was at work.

Our building was located near the edge of town, so I ventured into the countryside. It was early spring. I munched unripe wild berries growing in the bushes. They tasted sour, but I relished them. I was fascinated by bugs and watched worker ants labor for hours. After a few days of these solitary adventures, I grew bored and decided to sneak into Yi Suo to see the fruit trees and flowers. I scaled a back section of the wall and jumped. As I landed, a sharp pain shot through my heart. I ignored it. The compound was so beautiful compared to the drab streets of Xiangtan that it seemed otherworldly. I explored the grounds carefully, avoiding adults.

The following day I returned, venturing even farther in. One building in particular caught my interest. It was made of red brick with thick red elbow pipes jutting out from its sides like metal arms. It looked like a big red bug. The door was cracked open, so I poked my head inside. A man dressed in a navy blue uniform was standing in front of a boiler. I could see a roaring fire through its thick glass plate. The boiler room attendant looked at me and smiled.

“Do you want to watch the fire?” he asked.

I could have run away, but he had a friendly face and spoke in a soft, reassuring voice. He did not look like a typical boiler room attendant. His hands were clean and his clothes were not stained black.

“Do you like fire?” he inquired.

I nodded.

“Don’t be frightened. Come in and have a look.”

I hesitated.

“I promise not to tell anyone.”

I entered the boiler room cautiously.

“What is your name?”

“Jihui Peng,” I answered.

“I am Mr. Tan,” he said in a strong provincial accent, and then asked, “How old are you?”

“Eight.”

“It’s almost lunchtime. Why don’t you sit down and watch me feed the boilers?”

He slipped on a pair of thick canvas gloves, opened the heavy plate-glass door, and began to shovel coal into the burner. The fire surged. He continued for a while and then sat down beside me. We both watched silently as the boiler chewed its lunch.

“Why aren’t you in school?” he asked, finally breaking the silence.

“I’m sick, and the doctor told my mom I should stay home,” I told him.

“What’s wrong?”

“My heart hurts.”

Mr. Tan looked at me for a long while as I scrutinized him. Up close, he looked even friendlier. He had thick eyebrows and big, fleshy ears. His hair was cropped short and black. He looked my father’s age, around forty-five. After a while he stood up and I rose with him.

“Feel free to come back anytime you like,” he said.

As the days passed, I spent as much time with Mr. Tan as I could.

About a month after we first met, Mr. Tan asked a curious question as we watched the fire and ate our potatoes together. “Do you want to learn the martial arts, Jihui?” he asked.

“Oh yes! I dream about it,” I answered.

“I can teach you.”

I stopped chewing.

“You know martial arts?”

“I do. And I’ll teach you, but only if you agree to these two conditions. First, you must get here every morning by five o’clock and practice for two hours. Second, you have to promise to keep your training a secret. Do you agree?”

“Yes, I promise.”

“Good. We’ll begin tomorrow morning.”

I left the boiler room brimming with excitement. I ran back home imagining myself fighting and defeating everyone I passed. I was so thrilled that I failed to notice that my chest pain was completely gone.

That night I had trouble falling asleep; I wanted morning to come. Finally I dozed off, and when I awoke it was five minutes to five. I dressed quickly and quietly crept out of the house. I flew across the street, leaped over the fence, and made it right on time.

Mr. Tan was waiting for me and led me to a small wooded area behind the boiler room. “Your first lesson is Horse Stance,” he said, then demonstrated the posture. His feet were two shoulder widths apart, his knees were bent at a ninety-degree angle, and his spine was straight. He made it look easy.

“Now you do it,” he instructed.

I assumed the posture. Instantly my legs tensed, and after only a short while my thighs began to burn.

“One minute has passed,” he said. “Today you’ll hold the position for ten minutes.”

I began sweating. My legs started shaking.

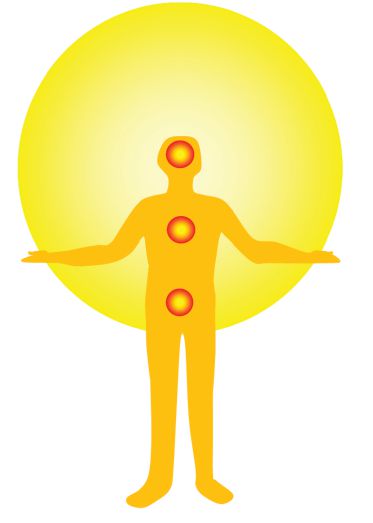

“Focus on your Lower Dantian,” he said, pointing to the area located below my navel. I did. The pain eased a bit.

“Five minutes.”

My legs were ablaze.

“Eight minutes.”

My backside sagged and he kicked it, saying, “Don’t cheat.”

My whole body was shaking.

“Nine minutes.”

My teeth started to clatter.

“Three . . . two . . . one. Stop!”

I collapsed to the ground. My lungs felt as though they were about to explode. It took me a while to recover.

“Are you all right?” he asked.

I nodded.

“Martial arts training is a long, hard journey. If you want, you can stop right now.”

“No,” I protested.

“Today we practiced Horse Stance for ten minutes. Tomorrow I will increase the time. Are you sure you want to continue?”

“Yes, Shifu Tan.” To emphasize my determination I called him by the traditional title used to address a master.

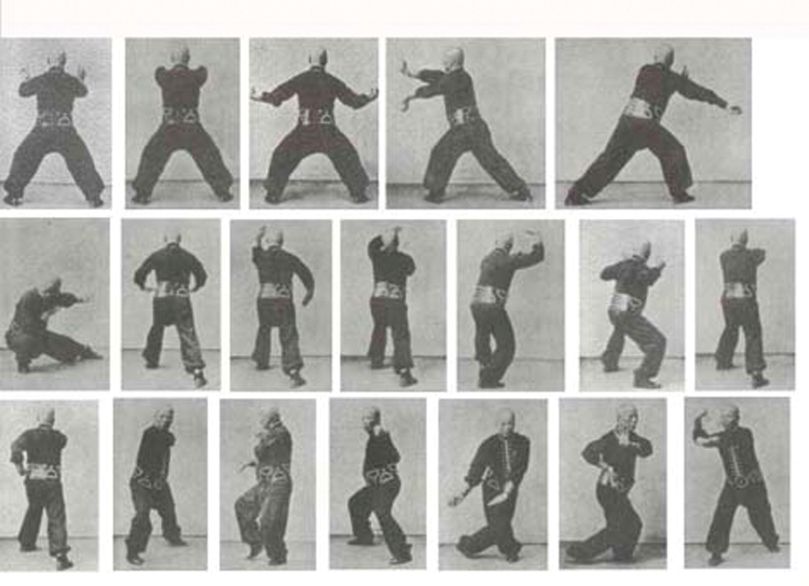

“Good.” he seemed pleased. “Horse Stance training is the foundation of the martial arts. Whether you punch or kick, you need a solid base. A strong root gives you power and mobility. And now I will teach you the first three moves of Tiger Fist Form, an exercise that will develop your grip strength.”

I spent the rest of the morning passionately practicing those three moves.

The following day I returned to the boiler room with mixed feelings, dreading Horse Stance and excited about Tiger Fist Form. Holding the position was unbearable, and as promised, Mr. Tan increased the duration by one minute. Over the next few mornings my enthusiasm waned steadily. I dreaded the short trip to the boiler room and I no longer ran there. I was losing heart, and in the back of my mind I began to wonder whether Mr. Tan was really a martial arts master or just a cruel prankster.

Then one morning Shifu Tan changed the regular routine and asked me to follow him inside the boiler room. There was an axe leaning against the wall, and he told me to pick it up. Then he took off his shirt.

“Swing the axe with all your strength and hit me right here,” he said, pointing to his chest.

At first I thought he was kidding, but he looked at me seriously. I didn’t know what to do.

“Don’t worry. You won’t hurt me,” he assured me.

I lifted the axe in the air and squeezed the handle.

“Hit me hard,” he instructed.

I waited for him to change his mind, but he didn’t. Finally, I swung down hard. The blade hit him squarely in the chest. I felt as though I had struck a hard object, not soft flesh. The axe was wedged into his breastbone. He stood calmly but I was terrified. I quickly pried the axe loose to minimize any damage. But there was no blood.

Only a white mark remained, disappearing after a few seconds, leaving no trace of the impact.

“Do it again,” he said.

I lifted the axe incredulously, and this time I swung harder. The results were the same.

“Go ahead, again, as hard as you can.”

Without fear, I swung the blade again with all my power.

“Do it one last time.”

I did. Afterward, he put his shirt back on.

“Come with me,” he said.

I followed him outside, and he led me to a sandalwood tree in the garden behind the boiler room. He pointed to the trunk. There were four blunt axe marks on the bark. Fresh sap was dripping down.

“Practice with sincere wholeheartedness, and miracles will happen,” he said.

After that day I practiced Horse Stance with renewed enthusiasm. Shifu Tan gradually increased the duration to twenty grueling minutes. He placed two bowls of water on my thighs, and he lit an incense stick under my bottom to keep my body from moving out of position. I learned to endure the agonizing pain.

About three weeks later I arrived as usual for my morning practice and assumed the Horse Stance position. After ten minutes I experienced a pleasant sensation building around the area on my midriff that Shifu Tan had asked me to focus on, the Lower Dantian. The feeling spread down my legs and negated the burning sensation. My body grew lighter and lighter. I felt as though I were riding effortlessly on an invisible horse. The tingling sensation in my Lower Dantian intensified, and I slipped into a trance.

When I emerged from it, the sun was shining high up in the sky, and Shifu Tan was standing in front of me.

“Jihui, you’ve been standing in Horse Stance for four hours,” he said, genuinely pleased.

From that day on I could stand in Horse Stance for long periods of time without tiring. The pleasant sensation now spread throughout my body each time. I enjoyed holding the posture for an hour or longer. The part of my daily routine I had hated most had become my favorite.

Around this time my mother grew suspicious.

“Where do you disappear to so early every morning?” she asked.

“I go jogging and exercise,” I answered, remembering my promise to Shifu Tan about keeping the training a secret.

“What about your—?”

“Mother, I feel fine now. My heart doesn’t hurt anymore.”

She didn’t quite believe me.

The following day I mentioned the conversation to Shifu Tan.

“Ask your parents to visit me tonight at the boiler room. And come with them.”

After dinner my parents curiously followed me to Yi Suo. We entered through the main gate. I led them to the boiler room and knocked on the door.

Shifu Tan opened it.

“Please come in,” he said warmly.

My parents entered. “Jihui, you wait outside,” he instructed.

My father and mother spent two hours with Shifu Tan. When the door opened again, they were all smiling.

“Jihui, keep training with Shifu Tan, and make sure you don’t slack off!” my father exhorted. Then they bowed reverently to him.

Two weeks later Shifu Tan formally initiated me as his disciple. I dedicated tea to Heaven and Earth, knelt down, and swore my loyalty to him as the fiery boilers watched. On that day my teacher became my master. ♦

Adapted from The Master Key: Qigong Secrets for Vitality, Love, and Wisdom by Robert Peng. Copyright ©2013 by Robert Peng. Published by Sounds True.

From Parabola Volume 39, No. 2, “Embodiment,” Summer 2014. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.