A new translation and commentary by Margo McLoughlin

Ambapali | Buddhist

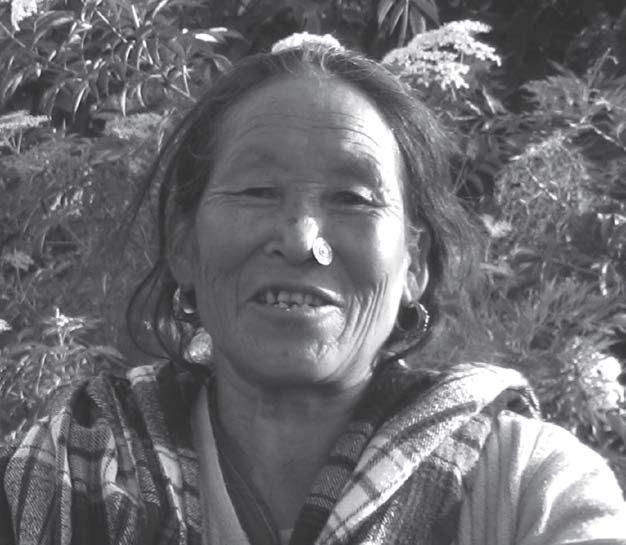

In Vesali, in ancient India, at the time of the Buddha, a baby girl was born spontaneously at the foot of a mango tree in the royal garden. She was given the name Ambapali. She grew up to be so beautiful that princes vied with each other for her hand. Instead of marrying, she became a courtesan. At the end of her life she joined the order of nuns and wrote a set of verses documenting with unflinching detail the changes she had observed in her own body. One can imagine that Ambapali, like many great beauties in literature and history, had seen her various physical attributes celebrated in verse or song. As a nun, practicing the Buddha’s teachings, she realized that suffering follows from identifying with any set of conditions, such as physical beauty, and she set herself to free her mind through the direct observation of impermanence.

One line repeats throughout these eighteen verses: What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt. Here the listener is reminded of the Buddha’s oft-repeated teachings on the unstable, changing nature of all phenomena. As Ambapali proceeds to describe the physical alterations in her body she is unsentimental and fearless. Instead of taking refuge in her beauty, which certainly brought her wealth and influence in her prime, she makes space for taking refuge in the Buddha’s teaching. Thus, her insight into impermanence leads to full and complete liberation of the mind.

The Verses of Ambapali

Black as night, like the down of the honey bee,

Curled and flowing was my raven hair—black silk.

Now, with age, it resembles strands of hemp.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Once fragrant as a basketful of blossoms

Belonging to the gods, my cherished tresses.

Now, with age, they smell like animal fur.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Like a well-planted grove in the forest, thick

And gleaming was my hair, adorned with combs and pins.

But now, with age, my locks are sparse and thin.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

My hair was a glorious shining mantle,

Braided and adorned with golden ornaments.

But now, with age, I am completely bald.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Like two crescents finely drawn by an artist

My brows were exquisite, alive with youth.

Now, with age, they only wrinkle and descend.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

And my eyes, like royal jewels, they shone

Sparkling and resplendent, long and wide and black.

Now, with age, they fade and dim; they shine no more.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

When I was young, my nose was delicate, yet firm—

A gentle peak, rising from the softness of my cheeks.

Now, with age, my nose is a shriveled shape.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

My earlobes were a thing of beauty, like bracelets

Fashioned and finished by a master craftsman.

But now, with age, they hang and droop.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

In the past, my teeth dazzled with their whiteness

Shining like the color of the plantain bud.

Now, with age, they are chipped and broken and black.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Once I warbled sweetly, like the cuckoo that lives

In the jungle-thicket in a grove of trees.

Now, with age, my voice is weak and faltering.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

I remember: my throat was like a conch-shell,

Well-polished by the sea, delicate and graceful.

Now, with age, my neck is bowed and bent.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Formerly, both my arms were round like crossbars,

Strong and beautiful. Now, with age, they are weak

As the limbs of the trumpet-flower tree.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Adorned with golden rings, smooth and soft, these hands

Of mine were fair to look upon when I was young.

Now, with age, they are like the root-vendor’s roots.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Once my breasts were round and full,

They rose up into the air, side by side.

Now, with age, they sag like empty waterbags.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Oh, the beauty of my body, in the past—

Like a sheet of gold, polished to perfection.

Now, with age, fine wrinkles cover it.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Like the elephant’s curving trunk, firm and smooth

Were my two thighs. That was in my youth, I know.

Now, with age, they resemble shafts of bamboo.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Smooth and soft, adorned with golden anklets

Once my calves were firm and full. Now, with age

They are like the twigs of the sesame plant.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Once my feet were elegant, like sandals filled

And stitched with cotton from the silk-cotton tree.

Now, with age, they are cracked and wrinkled.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt.

Such was this complex form, I called it mine.

Withered now and old, the abode of aches and pains,

It is the house of age. See the plaster fall.

What the Buddha has said is true—I have no doubt. ♦

(Theri is the Pali word for a female elder or senior nun. The Therigatha refers to the poems of enlightenment composed by the early Buddhist nuns.)