How do you heal from sorrow beyond compare?

In the beautiful woods of Newtown, Connecticut, a new elementary school is about to open. Pleasing to the eye and soul, this new school replaces the Sandy Hook Elementary School in which, on December 14, 2012, twenty young children and six adults were shot and killed by a lone gunman.

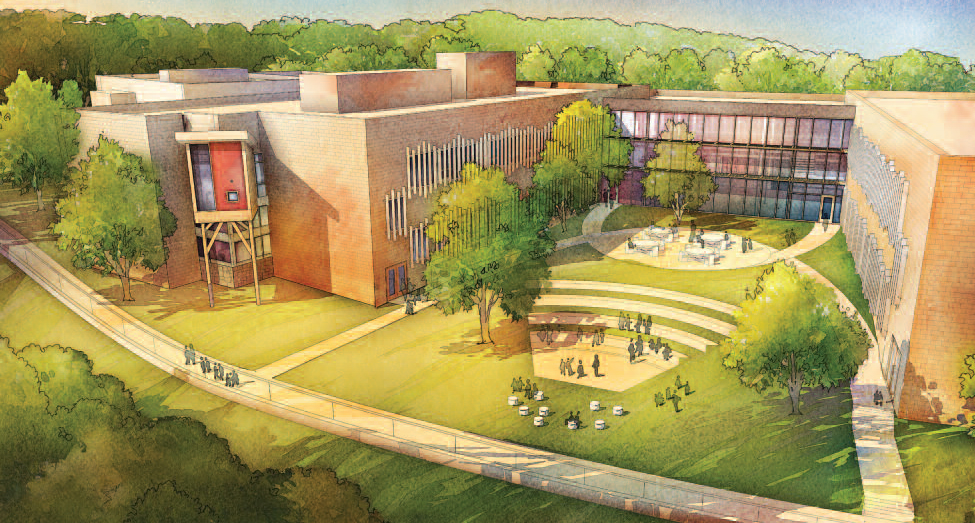

Not long after the shootings, the town decided to raze the old school and to build a new one on its site. The architecture firm chosen to design the Sandy Hook School was Svigals + Partners, based in New Haven.

In June 2016, Parabola sat down with Barry Svigals, founder of Svigals + Partners, to talk about the design and construction of the new school and the challenge of realizing its potential to help heal terrible wounds. We spoke in a cavernous room at the Yale Club in Manhattan, under the watchful portraits of several United States Presidents.

—Jeff Zaleski

Parabola: I thought we might start at the beginning of your relationship with Newtown, which presumably began the day you heard about the shootings. Do you remember that?

Barry Svigals: I remember it and in a certain way I put it aside in the sense that I didn’t want to get attracted to it. There’s a pernicious aspect to tragic events, which is that we’re drawn to them. So when I heard about it, and you know it was just everywhere for a while, it’s not that I didn’t get upset, but I didn’t lean into it. And that was particularly true when the RFP came out–the Request For Proposal for the new school. My first reaction was that it was so burdened that it would be an impossible job. It was only after a number of people had called to work with us on it and we talked in house, with my fellow architects, that it seemed obvious that we had to go after it.

P: You felt you had to pursue it. Why?

BS: It was a matter of service. We had specialized in elementary schools and it was what we had to give. It was in fact our greatest resource that we had to offer to what we saw was a…it’s such an overused word, but a traumatized situation. Going into it, though, we weren’t sure how to present it.

P: I understand that you said to the people of Newtown, in effect, “I can’t decide how this new school should look. You should decide.”

BS: Well, it was deeper than that. Nobody knew, including them, what was needed. And it wasn’t simply the school. The school was going to be a manifestation of whatever the process was. And the tendency for architects is to focus upon the result—to imagine what it’s going to look like. And how people will feel in it, all those things. We can forget to remain as long as possible with a question of what the need is. What are we serving? Often it’s much broader and something we can’t possibly know. The most important tool is to remember that we don’t know—an active not-knowing.

P: What’s the balance between not knowing and yet, from your experience as an architect, having a reservoir of knowledge and understanding that you could bring to this project?

BS: It’s quite a natural one. It is a wish to listen as deeply as possible. If there’s any single attribute of successful engagements around the making of something that’s to serve a need, it is that. And it’s a very particular kind of listening that allows for a transformation of a situation in ways that are inevitably surprising.

That listening also is something that changes the person who is speaking. It can be an encouragement. It can be that this openness can resonate in others, so that it is a shared openness. So in a way the person speaking is also listening to something that is larger than both of us who are speaking. That is, we’re in the embrace of this other that we don’t remember. That we’re not sensitive to and don’t realize that we’re a part of—a collective group. And this is what happened at Sandy Hook, where we had a lot of people whom we gathered to create an atmosphere of respect. Listening was essential in allowing what needed to happen, happen. That the transformation from the trauma and the grief and the loss into the creation of something that would serve children who had not yet been born, would happen—and to have the wish for our children to be fulfilled in some way. The school needed a process of that opening in order for people to participate.

P: Did you interact with parents whose children who had been killed?

BS: Yes.

P: How does your work on the school bring healing to people in their position? Maybe it doesn’t.

BS: Well one thing that was apparent is that everyone deals with grief in a different way. So the unfortunate…how do you even call it? The after-effect of their children being killed was that they were grouped together as “the parents of the victims.” They had nothing in common with each other, other than that, and it was not something they wanted to be connected with. This was a group they didn’t want to be a part of. And yes, there were opportunities for them to share an empathy that no one else could possibly share, but they were stigmatized. People didn’t know how to speak with them, how to relate to them, and so consequently they suffered many times over. It obscured the fact that each of them had a very particular situation and their own ways of trying to accomplish the impossible, which was to accommodate this event in their lives. An absolute impossibility. Because we were building a new school and in fact it only directly affected those who had children who were younger, who might go to this school, and so it didn’t have anything to do with them. And in another way it did, because their children lost their lives in a particular place and that had to be respected.

P: You’ve spoken of the importance of any architectural project recognizing the time and place in which it arises. In this particular situation, one wants renewal and a sense of hope in the building. And yet you don’t want to block out the past as if it didn’t happen. How did you approach this?

BS: You’re not successful if you try to block out anything, because that’s a futile endeavor. The approach that we took was one of inclusion, but perhaps a more enthusiastic inclusion of other aspects of the community that had a greater depth to them in a certain way, a historical depth. The rivers that run through the town. That is an important specific. The image of the town arising out of the rolling hills of Connecticut; and nature, the nature that’s particularly at that site.

We were just talking about the artwork that we put into the building, of ducks that used to be in the courtyard of the old school. We wished to have the ducks come back. And the characteristics of ducks, which flock: how extraordinarily communal they are and how sensitive they are to one another. They were representative of a current that we wished to be in and to be inspired by. So as you come into the school, two large panels depict these ducks flying out towards the south. Apparently we were so effective that last week a family of geese—a mama goose and five little babies—walked in the front door of the school. They had to shoo them out as well as clean up after them.

P: So what’s the function of nature in healing, and in architecture that heals?

BS: We’re a part of nature, but we’ve forgotten that we’re a part of nature. We have the opportunities to be inspired by nature in ways that animals perhaps are not inspired and yet we also can resolutely forget that we are a part of it. In the experience of the school we offer ways in which we can relate to nature, reminders of a profound connection that we share. When we say “with nature” it also connects us to ourselves and to each other as part of nature.

Now we also know that the way we live in modern-day life—all we have to do is look out the window here—we are almost resolutely in denial of the role that we play in nature. But we know, every one of us, that when we are in an environment where living things are growing and thriving, that it has an ameliorative effect on us. You can say it’s a healing effect. When we say that, we’re referring to a sickness that needs to be healed. The sickness we have as human beings is that we have lost this profound connection with ourselves and in nature. That seems extreme, but all we have to do is look outside or talk to one another about the stress that we have in life and we know that it is a sickness.

There is the concept of biophilia, with E.O. Wilson being one of the most ardent voices. He wrote a book on it with Stephen Kellert, who is an old friend of mine and whom we pulled into the project. Stephen was wonderful in reminding everyone of the opportunity of being re-enlivened by our connection to nature. Re-enlivened, literally brought back to life. Biophilia is really a love of life, a love of our biology, a love of nature. And that reminder is essential for us because we are in a great forgetting, and it’s a kind of inexplicable dynamic that we do forget. This is endemic to everyone. So we need to be reminded first of all to help each other remember that in this conversation we need to come back to ourselves in some sense and to re-connect with that movement that is there. Is always there when we return to it. That movement of relationship to the earth and to the sky, that vertical dimension.

P: Can you talk a little about architecture in general used as a means of healing?

BS: Architecture can do only so much. However, it can do a great deal in offering people first of all a connection to the outside. The views to the outside are extremely important and that’s why in these transparent buildings where all the offices can have a view, fewer people are sick. It’s been documented quite clearly that people are better off if they have a connection to nature, even representations of nature like the ducks. My friend Stephen would go through Grand Central and point out all the biophiliac aspects to the design of Grand Central—that they’re floral, things that relate to animals; those kinds of representations actually have an effect on our psyche. We recognize that we’re a part of a life force. And then it gives back to us. As we know, these relationships are symbiotic—at their best they’re reciprocal; reciprocal feeding is what’s happening all the time, and that reciprocal feeding, a cross-pollination, is essential in our well-being.

So how can you promote that in a building? In cities it’s very difficult but it’s possible. There are rooftop gardens, windows to the outside, things like that. In a setting like Sandy Hook, to come in that front door and immediately to see outside. As soon as you walk in you’re outside again and we have these metaphoric trees in the lobby and beautiful artwork by Tim Prentice, a mobile of leaves that are just rectangles in aluminum that reflect the light and reflect the colored glass. And then you have the trees right out there. We pushed the school right to the edge of the site to be in the trees, and the image that we had from the very beginning was, learning in the trees.

P: I want to ask you about security because I know that was a concern. I told someone about what you’d been doing at the school, about how there was an interior that related to nature and was healing, but also about how at the same time there’s a certain vigilance in the structure of the building itself. And she said, “It reminds me of mindfulness meditation,” in that you turn yourself inward and yet at the same time you’re aware of everything that goes on around you. How did you meet the challenge of integrating the elements of security into this other vision you had of healing through nature?

BS: The most important strategy was to keep our eyes on the essential task that we had in front of us, which was to create a wonderful and inspiring place for kids to learn. Within that, all kinds of issues can be resolved, from how to keep the rain out to how to keep someone who is an intruder out. We had very in-depth collaboration with our security consultants.

So we walked around the very first day that we were on site after we had gotten the job. The security consultant and the landscape architect, everyone was there, the interior designer, walking around the site talking about making a wonderful place for children to learn. At one meeting, when the security consultant, Phil Santore, was asked, “What’s the most important thing with respect to security?” he said, “The most important thing with respect to security is that the children have a wonderful, delightful place to learn.” So, for example, there is the bioswale [ground covered with vegetation]. Now, we want to have a bioswale, so the kids can see it every morning, and it fills up and they have nature in front and in back of the school. And there are theses little metaphoric bridges. They’re not really bridges, they’re right in the grain, and they slope down into the bioswale with railings, so you feel like it’s a bridge going over this bioswale in front of the school—and they represent the bridges that are in town that are going across the Pootatuck River. And the bioswale happens to be a deterrent as well.

P: It provides line of sight to detect any intruders.

BS: The meditation analogy is a true one in that we’re concerned with what’s happening in the school, and it’s been proven that the most effective security is being able to see in the distance. It’s not to create a fortress, which was the idea in the 1970s, to create a fortress—which

we know….

P: I know you encourage children’s imaginations in your school projects. You have a program called Kids Build, which was employed at Sandy Hook. Can you talk about that?

BS: We think it’s important for the children to benefit from the very unique circumstance of the school being built and the feeling of participation in it. We bring them in during the design process and have them visit the office. We come to the school and make presentations. And we bring them into workshops. We had a half-dozen workshops during the course of the last three years. They all have to do with understanding the school and how it’s built and what’s important in it, and to feel in some way connected to it even though we’re dealing with second- and third- and fourth-graders.

P: So, very young children.

BS: We wanted them to draw and to make things that had to do with nature. And we had a table of twigs, leaves, pine cones, all sorts of things you would find in a forest. And in fact, some of those items came from behind the school. The children were working in threes, and they would pick out an object that they wanted to draw. One of them would hold the object with these little tweezer-like devices and another would hold a light, and the third would draw the shadow of the object. And then they’d switch. The concentration and the attention they gave to one another was so touching. They wanted to hold the leaf steady for the other one to draw.

P: Have elements of that experiment been incorporated into the building?

BS: We took these drawings, and in the front facade we took this canopy of trees that’s suggested by the undulating facade and aspects of the building, these long windows that are metaphoric tree trunks, and underneath a number of them, there’s a panel that is being carved right now from these drawings, which has been inspired by the hearts that are carved on trees. That impetus to carve a heart in the tree. And so here are these children’s artwork carved on the tree that comes from their attention, their love of doing something that’s fun to do. And so it’s not about one kid making some art and getting their name on it. It’s about everyone participating and about how they needed to work together in order for the artwork to appear as a carving of their hearts on the school. That is just now being colored and is one of the last things to go into the front of the school.

It’s resonant with the need for every community to recognize that they need to renew their community periodically. The building is a result of this process, and it was one of listening, in a group when people began to speak about what they loved in their community. This was an important piece—that the questions we asked them didn’t have to do with the school at first. Because the process couldn’t start with that. But it could start with what they loved about their community, what they loved about their homes, what they loved about living in Newtown. And people brought in pictures and spoke about these pictures, showing them to everyone else. And when you hear someone speak with a real love for a place or an aspect of their community, people feel that love. People feel it. And that feeling, and that kind of communication, binds people together. It reminds them that we are more similar than we are different. And that remembering is an essential part of creating any school that’s connected to the community.

There is a kind of remembering that is about the past and there’s a kind of remembering that is about the present. It’s about bringing yourselves back again as a community. Re-membering your community. That dynamic of bringing a community back together is similar to the one that we as individuals also reflect, which is a remembering of ourselves, bringing ourselves back together because events, traumatic events, fracture us. The trauma of life, your getting here, my getting here, in the city traffic or by public transportation. We have inured ourselves to it to a certain extent, but not entirely. We’re traumatized by it. And consequently we need to do all kinds of therapy. We need many therapeutic interventions to get ourselves back to a baseline where we’re more fully human. It’s so elemental, to be so fully human. To fulfill what it might be to be a human in life, to be in life, and to contribute to life.

P: What did this particular experience teach you about that? I would imagine that there were elements of trauma for you in working on this project. That it was emotionally very painful at times. And yet I’m sure that it must have helped heal something in you, in some way. You weren’t apart from it, you were a part of this process. How was it for you personally?

BS: I would like to believe I was no different from anyone else in this. Again, it’s collective, and the collectivity began within our own office, which is highly collaborative, and very communal. So no one ever felt alone in this process. The challenge was deeply shared, and that changes everything. We know that when people feel isolated, it only intensifies and deepens their loneliness.

P: The shooter being a case in point.

BS: And others, more recently. So, when we look to what can address these situations, there’s nothing prescriptive that we can do except look to each other.

P: The school is scheduled to open when?

BS: The 29th of August. The first day of official school.

P: So on August 29th some little kids are going to walk into that school for the first time. What would you like them to experience? What do you think they will experience?

BS: I want them to smile. And I want them to feel the embrace of the building.

The town’s First Selectman Pat Llodra spoke at one of our events. She said to the sea of people who had been working on this site, “Thank you all for being here, thank you for doing what you’re doing. My wish is that the love that you have for what you do will be in this building, so that when the children come in, they’ll feel that love.” And my wish is that when they walk into this building, they’ll feel the love that so many people have put into this building, and I think they will.

Just when you’re asking me this, this is the first time I’m allowing myself to reflect on that. Until this moment, I was still worrying about the pencil sharpeners getting in there. ♦

This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.