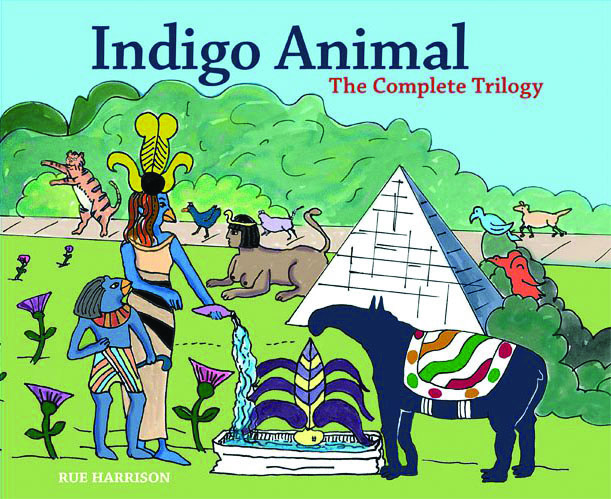

Indigo Animal: The Complete Trilogy

Indigo Animal: The Complete Trilogy

by Rue Harrison. Porch Lion Press (www.porchlionpress.com), 2016. PP. 320. $29.95

Reviewed by Bob Scher

Indigo Animal is original, delightful, and profound. The artist, Rue Harrison, has given us wonderful characters in illustrated books in which she has raised the bar on a certain kind of content. These are all woven together in a startling exhibition of inventiveness and craft.

Indigo Animal is a tale about finding one’s direction, both inner and outer—we might say “the unconscious becoming more conscious.” But Indigo Animal is not an allegory. One of its remarkable properties is that these aims are explicit in the book. Yet there is no pretentiousness, superficiality, or onerous preaching. The beginning:

Every morning, Indigo Animal wonders, “What’s my purpose in life?”

On long, solitary walks, Indigo Animal ponders this question and discovers there are no easy answers.

And from there the book takes off.

Indigo Animal is circumspect, thoughtful, and shy. His large dark indigo body, contrasted with that of other beings, seems to be full of mysteries of which Indigo is not yet aware. Indigo Animal also has a strong connection to classical lawn statuary, and setting the tale in such a seemingly quirky domain is one of the striking aspects of the book. Everything important one needs to know can be supported by any reasonable outer pursuit, if one is willing to face what is unknown. (Some may even find themselves becoming captivated by lawn statuary.)

One of Indigo’s traits is that in spite of his inner reserve, “[He] increasingly feels the impulse to explore streets that lie beyond the known territory.”

This new stage in his life’s journey begins when squirrels steal his TV. He faces the VOID—but then discovers that he is actually glad that the TV is gone. Later:

The theme tune from Jeopardy, that’s been playing in Indigo’s head, stops!

Indigo Animal is energized by heretofore unperceived vibrations.

One of the themes in the book is that when one’s truer feelings are strong enough, they may attract what is needed. But there is no artifice; events happen naturally. Indigo has studied classical lawn statuary in his neighborhood for a long time and has read much. But he feels the lack of a deeper knowledge. He discovers on a match-book cover the existence of the Lawn Statuary Research Institute, LSRI, and enrolls.

Indigo Animals are creatures of fascinating complexity. Perhaps that is one way to explain why Indigo Animal, after so looking forward to going to LSRI, wakes up on the first day of class saturated with a feeling of unspeakable dread, which quickly translates itself into a series of excuses explaining why it is no longer necessary to actually go there.

“It’s too much to ask of a shy, solitary animal such as myself.”

“Who else can properly keep an eye on these precious lawn statuaries and stave off vandalism?”

“Besides, my research is too important

to interrupt.”…but the long-established morning routine will not be denied. And so it happens that, during stretching, a question begins to free itself from the depths of Indigo’s unconscious mind.

It rises closer to the surface during coffee…

Then in a remarkable turn, the author undermines our expected inner argument—that Indigo would succumb to and decide after all to enroll. Instead she gives us an amazing episode in which the conclusion requires no further explanation.

…And [the question] finally breaks through, “If I DID go to LSRI today, which blanket would I wear?”

(Indigo always wears a blanket.) And what a marvelous sequence this is. We also experience another side

of Indigo.

“This gauzy blanket is too formal for school.”

“In this blanket I have gone where no other indigo Animal has gone before.”

—and with good reason!”

(This blanket is attached to an enormous parachute.) Indigo examines many more blankets, each more bizarre than the previous, until he finally recognizes his “power blanket.” Nothing more needs to be added.

At LSRI we meet many intriguing beings:

Yeti and Wombat are quiet, unassuming animals who turn out to be ingeniously helpful. Dame Eleanor Marmot was Fountain Restorer to the Queen, but is now relegated to a neglected classroom at LSRI. She was an eminent scholar, sings ancient ballads, and one of her favorite philosophers is Marcus Aurelius, whose few words surface in old books that help Indigo at critical moments.

And how often does a carnivorous Komodo Dragon appear heroically in a story about self-realization?

Aside from the harmonious pages, the drawings are so precise that just by looking we have impressions of a character’s inner nature. Harrison is a master of postures. Characters have characteristic postures that are windows into their interiors. And there is movement in these pages. The reader may sometimes feel like she is going to the theater. Movement also serves to emphasize the many moments when Indigo is still.

An important element of Indigo’s being is his connection with his body. When tired, he rests; in difficult moments, he remembers to breathe. And when he walks, we can almost feel his weight.

Indigo possesses an admirable quality of restraint coming from his natural shyness. But when called to support or defend what he knows to be of value, he has to overcome this shyness. This does not happen cheaply in Harrison’s book. She conveys his inner conflicts realistically. We feel the difficulties when he has to go against himself. And when he does, he discovers new possibilities in himself and in his actions.

The story works on many levels because life, when lived less cluttered by preconditions, reveals its depths. As the book progresses, a related theme is the need for a certain level of sensitivity. Harrison softly indicates that without this a genuine search for one’s self-worth cannot continue. And out of this search arises a deeper connection with others, especially with beings with whom both we and Indigo do not have a natural affinity. This is the ground from which a more conscious love can spring.

Indigo Animal is a beautifully bound hardback, rich in color, and even the paper feels good. ♦

Bob Scher is the author of Fear of Cooking (1984), Lightning, The Nature of Leadership (2003), and As If The Sky Were Open, Selected Poems (2009). This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.