My father had many good qualities; unfortunately, equanimity was not one of them. Known for a ferociously bad temper, he once threatened a one-armed theater manager with the demolition of his entire theater if he did not refund our ticket money because he deemed the film inappropriate for his ten-year-old daughter. Needless to say, it was easier staying out of the house than in the house and so, nature deprivation was something I did not suffer from as a child. Yet nature deprivation is a very real problem for students and young people today and it is especially concerning as the planet suffers a continual environmental onslaught and decline. To save the planet, children must learn to love and value nature. Perhaps a calling card from Laozi is required.

The classical philosophies of China (Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism) developed during the Zhou Dynasty – specifically during the “Age of Warring States” period of the Zhou Dynasty. The Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 221 B.C.E.) is remembered in World History for two primary reasons. The Zhou rulers were the first Chinese rulers to establish a belief in the Mandate of Heaven. The Mandate of Heaven was the Chinese belief that the gods granted the emperor the right to rule or mandate as long as the ruler ruled competently and well. A bad emperor, however, could lose the Mandate of Heaven. If floods or famines or war ravaged the land, then the gods signified their displeasure with the emperor and rebellion was justified. The concept of the Mandate of Heaven led to a dynastic cycle – or new dynasties overthrowing old dynasties.

The Zhou Dynasty is also remembered because it was the time period of the great philosophers of China. During the tumultuous period of the “Age of Warring States,” the Zhou rulers were not able to subdue the lords of the land and fighting ensued. China collapsed into a kind of “Game of Thrones” with competing lords attempting to overthrow the Zhou in hopes of establishing a new dynasty. It was as a result of the chaos caused by this warfare that the great philosophers of China attempted to create philosophical systems that would restore peace and harmony to China. Confucius taught that order was the key to restoring peace with superiors ruling benevolently accompanied by inferiors in obeisance, Han Feizi – the famous legalist scholar – disagreed. Han Feizi maintained that people were fundamentally selfish and only rewards and harsh punishments could ensure societal order. And then, of course, there was Laozi.

Laozi had a completely different take on the chaos and disorder that China was experiencing and a completely different remedy for China’s ailments. Laozi did not believe that book learning would solve China’s problems – Confucius, of course, did and he emphasized that the highest state a man could achieve was that of scholar-gentry. Laozi, however, believed that a government constantly interfering in the lives of its people could never restore order. He believed that a government that governed least was the government that governed best and that people left to discover their own natural selves and living in close proximity to nature would inevitably be the happiest and most peaceful people on the planet. Laozi was antirational because of his rejection of book learning in solving humanity’s ailments and also a nature lover because in nature, he saw a kind of perfection that was not accomplished by man’s meddling. Laozi was the original organic hippie farmer. He would have been perfect in the Sixties:

“I cannot make a tree grow or flourish” [said the gardener]…“All I do is avoid hindering a tree’s growth – I have no power to make it grow.”

“Would it be possible to apply this philosophy of yours to government?” asked the questioner.

“My only art is the growing of trees,” said [the gardener]. “Government is not my business.” ―Liu Zongyuan, Chinese scholar-official, circa 800 C.E.

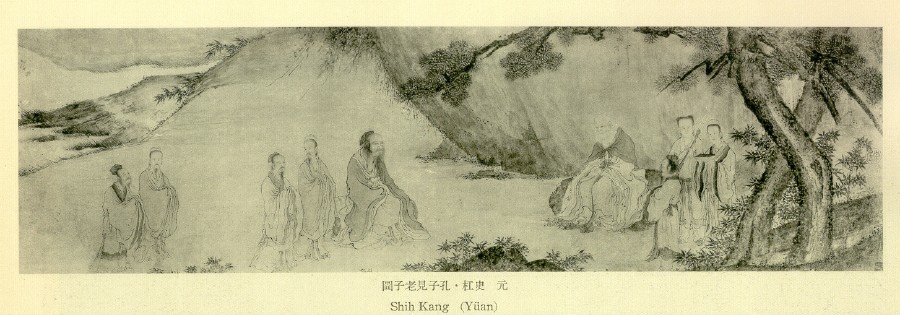

Of course, the Chinese ultimately embraced aspects of all three philosophies as did the emperors and years later, after the collapse of the Han Dynasty – a dynasty that had adopted Confucianism as the official dynastic philosophy – Buddhism gained in popularity too. The Chinese soul is an eclectic soul but it is in Daoism – the philosophy of Laozi – that the Chinese soul is connected to nature. It is in Daoism, that landscape painting and gardening capture the Chinese imagination. Rather than an enormous Mona Lisa with tiny trees in the background, man is small and the mountain is majestic. In Laozi’s philosophy, nature takes center stage and man is but one of many minor characters on the stage.

So, how do these reflections on the Zhou Dynasty connect to the classroom and why should the classroom teacher connect her students to nature – especially if the curriculum is not specifically related to nature? Before I even attempt an answer, I am brought back to childhood. In the town where I lived, there was an abandoned factory. It was a rather small factory and it had made some kind of condiment – kind of like a sweet and sour sauce that could be added to poultry or vegetables to make the cook appear more sophisticated than she was. The factory was beside a stream and in the summertime, the stream was warm enough to wade in. As part of the neighborhood’s marauding band of children on summer vacation, I regularly went down to the stream and waded in the water with the other kids. The boys would sharpen sticks into spears and the girls would direct the boys to these large fish that we referred to as sucker fish. As I recently looked up whether such a name was actually given to a fish, I discovered that indeed there is a sucker fish but I am absolutely certain that this was not our fish. We had simply given an incorrect name to a fish and for some reason, it stuck. I also realize that gender was still very restrictive in the seventies because the girls never sharpened the spears or attempted to kill the fish. The girls pointed to the location of the fish and the boys tried to spear the fish. Summer after summer, we engaged in this activity and summer after summer, we never managed to spear a fish. I think it had less to do with skill and more to do with desire. The boys didn’t really want to kill anything; they simply wanted to appear like hunters. We spent hours in that stream – usually after we had spent the mornings swimming in the town pool.

At the town pool, there were many adults and so, it felt a bit restrictive. But by the abandoned factory, there were no adults and so we learned how to cooperate with one another, how to fight with one another, and how to make peace with one another. We also learned how to endure unpleasant conditions – as it was usually really hot by the stream and the water was not very refreshing. More importantly, we learned about nature. How the rain increased the water in the stream and how litter and trash really mucked up the stream and how certain insects lived in the stream. We were not like scientists because we did not care much about accuracy but we were connected to the stream because we went to it day after day. Looking back, we liked the freedom of being away from adults and in nature – outdoors – we were free.

Thinking of my own children, I know that I would probably have been more intrusive in their play. They are older today but when they were young, I would have worried about my children being alone by an abandoned factory and I would have wanted to know who was in the group and whether an adult was nearby. As much as I might be tempted to blame nature deprivation on video games, cell phones, and too many screens, I know that screens are only one part of the equation. Truth be told, adults today are a bit too intrusive in children’s play and so, a rather dangerous mixture of too much electronic distraction and too much adult meddling leads to too many children who don’t play in streams and this may be most problematic of all. It is good to play in streams, especially when a child is young – well, at least, streams that are shallow, where drowning cannot occur. Even there, I betray myself – not totally connected to Laozi – I have a fear of nature too.

Yet in nature, children learn about nature and about the need to preserve streams and fields, flowers and trees. But children learn even more than that. They learn how to entertain themselves and how to endure discomfort and how to find beauty in unexpected places. Like climbing a mountain and being exhausted, there is that magical moment when your foot arrives on a peak and you can see for miles. It puts your being in perspective and shows you how awesome this planet is. When children are connected to nature and brought outside, the classroom becomes more expansive. It is a reminder that learning can occur anywhere – not just at desks and behind walls. It is a reminder that learning is everywhere but of course, you must look. In nature, you cannot only look at your feet. You must also listen and be attuned to what is around you. You see more deeply and you listen more readily. The lessons learned in nature are expansive and teach the whole child.

Playing outdoors and in nature also teaches the child the power of nature. To be in a field when the sky suddenly darkens and the lightning storm begins is to learn that nature is like a two-headed being, at times beautiful and pleasant while at other times dangerous and frightening. It is to recognize that beauty and fear often walk together and to learn how to survive even when conditions change. To this day, I know how to build a lean-to, start a fire, and distinguish edible plants from poisonous ones. While I most definitely would die on some wilderness survivor show, I could survive a few days in the woods waiting for the tow-truck. Yet there is something even more important about playing outside and bringing the classroom outside. It is to learn that the world is big and to have a respect for it. Like that public service announcement I used to watch as a child – the one where the Native American Indian sheds a tear over the garbage littered across these majestic lands – I know that the earth needs our loving attention and our loving hands and I stand in awe of its awesomeness.

I also know what playing in nature can do and what it cannot do. My days by the river did not make me less germ phobic. I still am uncomfortable with outdoor cloths on the bed. And I am most certainly not less allergic after all those days spent in fields and haylofts and by streams. My asthma is easily triggered by pollen and forget about ragweed, it can kill me faster than an AK-47. But to this day, if the sun is shining, I long to go outside. No screen can hold my interest if I have leisure time. If the sun is shining, even if only for an hour, my walking shoes go on and outside I walk. Playing in nature has allowed me to know that I am part of nature, part of the web of life.

Of course, the best way to instill a love of the outdoors in children is to set a good example. When the sun is shining, the television or computer screen or cell phone should be set aside and the children should be brought outside. Too often I see an adult with a child at a park and the adult is checking his phone, telling the child to play. If the adult does not enjoy the outdoors, it is unlikely that the child will. But if the adult turns the phone off and says, “My goodness, look at that beautiful sky. That cloud looks like a witch on a broom. What do you see? A cat chasing a feather – yes, I see that too. Let’s go follow that cloud and see what else we will find” – then the child will see what a wonderful world it can be.

The birds have vanished down the sky.

Now the last cloud drains away.We sit together, the mountain and me,

until only the mountain remains.―Li Po, “Zazen on Ching-t’ing Mountain,” translated by Sam Hamill from Crossing the Yellow River: Three Hundred Poems from the Chinese