When I was three or four years old, I started to grow afraid that I was evil. That year I had the worst nightmare of my life thus far: intense, consuming, and hyper real in the way that only very young children’s nightmares can be. In it, I walked from my bedroom down the creaking stairs of our two-hundred-year-old New Hampshire farmhouse, drawn inexorably toward the warped glass panes that framed our front door. Outside was black dark, a hot and windy late summer night. The ghostly face of a woman floated beyond one pane, buoyed up on the wind. She was looking for me.

She smiled.

She snatched me and my baby doll through the windowpanes and took us far away, to her storybook witch’s cottage in the heart of a storybook wood. There she dissected and rebuilt my doll, methodically peeling open her plastic torso under sourceless, Disney-villain-green glowing light. I could only watch, helpless . . . until the witch turned her green light and her hands toward me.

When she finished remaking me, I was no longer helpless. I was like her. We worked together for years (my dreams still sometimes span so much time that I’m surprised not to have aged on waking), my reanimated baby doll bringing us strange potions from realms abroad and watching us mix them with radiant green eyes.

Perhaps a century passed. Then, one night, I looked out of the cottage window and saw two figures emerge from the trees and climb over the hill toward us. As they grew closer and closer, I saw that they were very old men, bearded, weathered, and gaunt. When they were only feet from my window I recognized them: my father and his best friend, torn and bent by their lifetime of desperate searching, never giving up hope that they would find me at last. I saw a fathomless sadness in my father’s eyes. And here was where the nightmare reached its peak: I looked in my father’s face, and I laughed.

Four-year-old me woke up screaming. I screamed and screamed for what felt, for a small child, like hours, until at last my mother came into my room and hugged me and asked what was wrong. I told her about the kidnapping witch, but I knew I couldn’t speak of the end of the dream, the part that had really frightened me. The shame of it already went too deep.

Whenever my mother came in to comfort me at night, after all those times I woke up screaming (which started happening more often that year), she would tell me to pray. I recited “Now I Lay Me Down To Sleep” and “Thy Ocean Is So Big” in a quavering voice, repeated the prayers like a Protestant rosary when my mother left the room. They helped.

But now—now I have realized that nightmare in a very literal way. In my spiritual life I call myself a witch, and if my estranged father showed up at my far-away cottage window, laughter is a gentler response than he or I could hope for.

When I was three or four, as close as I can figure, is when his abuses started; those nightmares are two of the only clear memories of that year, which has mostly changed to a sticky, toxic murk in the back and the bottom of my mind.

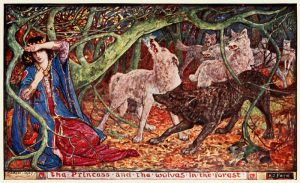

The Gothic imagery in my childhood dreams—witchcraft, dark forests, old houses—has helped me to sort through that murk, though. The symbolism of the Gothic is like that of the fairy tale: it gives us a code for the unspeakable.

I certainly was not raised a witch. My parents took my younger sister and me to a sedate Episcopalian church about a ten minute drive from that old farm house. I had my First Communion and Confirmation there. I liked church, the meditative quality of the service, the chance to sing without being singled out, the opportunity to dress up; I liked the taste of Communion wafers and wine, and the awe and drama of Bible stories. I loved our gentle and erudite minister, Mr. Ervin. And I believed in God.

When I was thirteen, I even became what’s called a born-again Christian. I said a fervent and sincere prayer, acknowledging that I was a sinner (that much had always been obvious, the shame only building after those early nightmares and the nameless memories that inspired them) and accepting the lord Jesus into my heart as my one and only savior. My relationship with Jesus felt very personal. I would often talk to Him in my head as I walked from my boarding school dormitory to morning classes, telling Him my daily worries and thanking Him whenever I saw a particularly beautiful sunset or tree.

But then I got kicked out of boarding school and sent back to the parental home that still held for me that nameless fear. The therapist I’d worked with at school had looked at me piercingly and told me to be careful back there, to try to find school activities and summer jobs that kept me out of the house as much as possible. I couldn’t ask her why, but I didn’t need to; I knew she was right.

I’d never felt more like a bad person, like exactly the kind of sinner that needed a Christian God’s love and redemption, than the year I left boarding school; but that year was also when my faith began to fail me.

At first I thought it must be my fault, that I hadn’t yet been really “born again” after all. So I repeated my saving prayer, the one that was supposed to transform my heart, several times over in the coming months. Every time I searched my soul for some seed of hope, some hint of redemption, and I was convinced that the sameness I felt was all my fault, not God’s. That I simply hadn’t followed the rules closely enough.

But slowly my pact with God dissolved, and I became untethered.

The path to my current understanding of my faith is much less clear. It is a tidal cycle, an edgeless movement in and out of ideas, traditions, understandings. Sometimes I call myself a pagan, sometimes agnostic, usually a witch. My husband and I were handfasted by a Celtic druid; I loved the ceremony. I say a prayer and light a candle for the triple goddess at each turning point of the year.

But my journey toward a self-styled paganism has been so gradual and fluid that at times it doesn’t seem like a journey at all, and it is still not easily bounded or defined. I feel increasingly drawn toward the kind of intersectional, open-ended spirituality that my mother would call noncommittal, wishy-washy, or even cowardly, as she described our Unitarian neighbors.

A faith that is fluid, boundless, changing, cyclical, open: this is a faith that one might call feminine.

Is it a coincidence, in our patriarchal society, that those very qualities are disdained by the hegemonic Western religions? Millennia of carefully preserved dictates, complex hierarchies, rigid taboos, venerating the Heavenly Father.

I believe in the importance of the divine masculine, too; and of course I know that not all iterations of Abrahamic faiths are so unbending. My childhood minister, Mr. Ervin, often said how glad he was that our church was named St. Thomas, for the doubter, and that Episcopalianism left room for freedom and thinking.

I think he was right; but I cannot pray to a father God any more. I do not want my God to be the things a father is to me. Maybe that’s not fair, and I have so many respected and beloved friends who know and love their father God. I hope that if I have children one day, I might be able to see the divinity in fatherhood again.

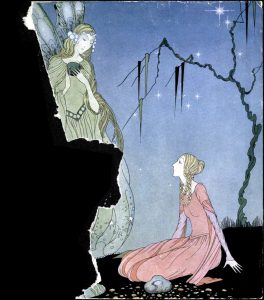

But my god now is not the God of masculine strictures, of fear and obedience, of capital letters. My goddess and my practice is quiet, inconstant, and mostly solitary. My faith and rituals and prayers aren’t for forgiveness, but for peace and hope. Where once I asked God to wash away my sins, to take away my evil, I ask my goddess now to help me find my own goodness and strength, to help me believe that I deserve life and blessings. And like the best kind of mother, sister, female friend, she helps me to see that I was always good and strong.

Finding my feminine faith has helped me to see the divine feminine in myself. I don’t mind when my kind of faith is trivialized or derided; many feminine things are. Those of us who embrace the feminine know its strength.

And my nightmares about my father are fading away, growing less and less frequent. I am not so haunted by my own evil anymore. Where once I prayed for forgiveness from a father God who held up huge palms and said “Thou shalt not,” now I find peace with a sister god who takes my open hands in hers and says, “You will.”♦