The sacred pipe of the Native Americans is a potent symbol of relationship. Through it the human breath sends to all the six directions the purifying smoke that connects the person to the divine and is the link between all forms of life: mitakuye oyasin, we are all relatives.

In the Foreword to The Sacred Pipe*, Black Elk is quoted as saying:

“Most people call it a ‘peace pipe,’ yet now there is no peace on earth or even between neighbors, and I have been told that it has been a long time since there has been peace in the world. There is much talk of peace among the Christians, yet this is just talk. Perhaps it may be, and this is my prayer that, through our sacred pipe, and through this book in which I shall explain what our pipe really is, peace may come to those peoples who can understand, an understanding which must be of the heart and not of the head alone. Then they will realize that we Indians know the One true God, and that we pray to Him continually. ”

On a recent visit to Joseph Epes Brown, we were shown a beautiful pipe and a braid of sweet grass, and he told us the following:

This is the pipe that was given to me by an old Assiniboin when I was traveling west to find old man Black Elk. I found out where he was, in Nebraska, and walked into his tent with this pipe, and I prepared it and lit it and puffed on it and passed it to him. And he puffed on it and passed it back. I was getting a little bit uneasy, and he looked at me and said, “I’ve been expecting you. Why did it take you so long to get here?”

The sweet grass is mostly to add some fragrance, like incense. Back in Maine when I was a boy, I made friends with some of the Abenaki people there. They used to hunt on our land, and they would give me these braids of sweet grass.

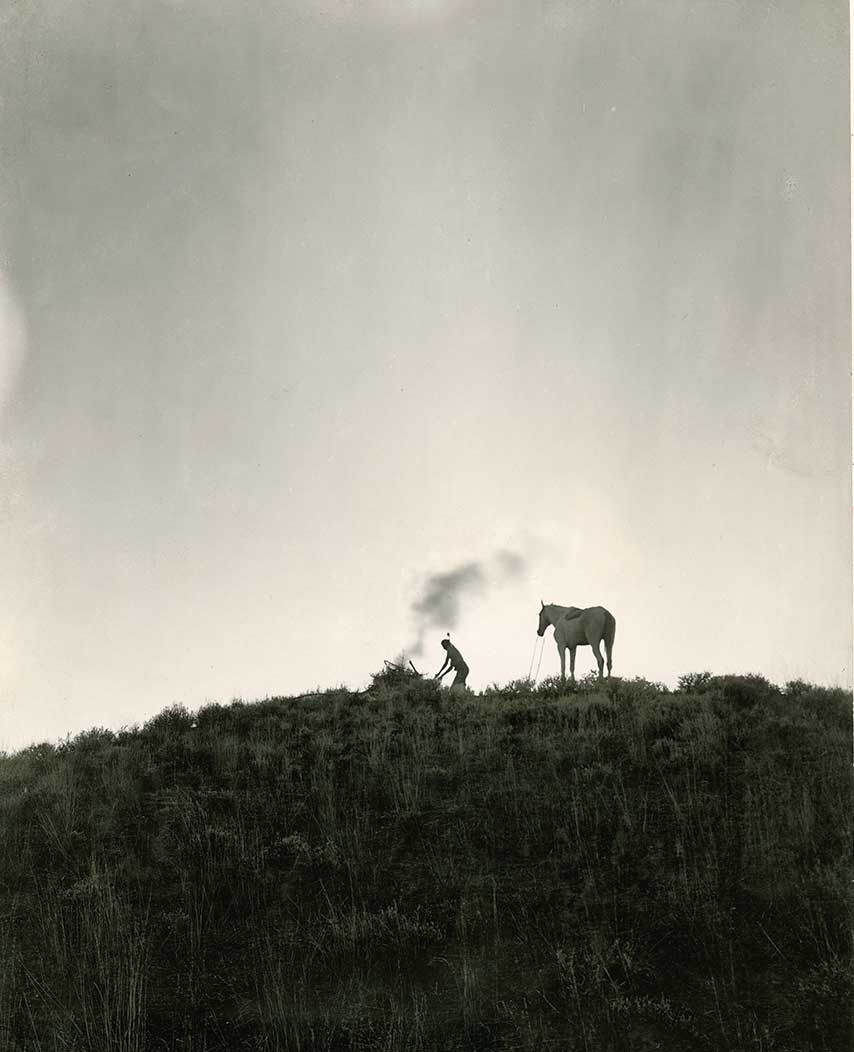

Once the pipe is lit, it is very important to keep it going. They pass it around the sacred circle where the Sun Dance takes place, and they use it to smoke people with, too—they smoke the dancers, as part of the ceremony. There’s a lot of smoke, believe me.

I remember how much Black Elk used to smoke. He smoked violently. He would actually disappear in the smoke: smoke would seem to be coming out of his ears and eyes.

The pipe is always associated with the center. It is pointed to all four directions in ceremonies like the Sun Dance, then pointed above and below as well. It ties them together— the horizontal and the vertical. That’s very important. The symbolism is very rich. For the Indians, the smoking of the pipe is the same as taking the Eucharist to a Christian.

The bowl of the pipe is essentially the place of the heart, and the stem is the breath passage. There’s also the foot, on which the pipe rests.

They associate the pipe with the human person: it’s anthropomorphic symbolism. Like a pipe, a person has a mouth and windpipe, he has a heart, and he has a foot. And his heart is where the fire is. In the pipe it is the point of interception, where the tobacco burns. In the ceremony, they designate each pinch of tobacco: this one for the winged of the air, for example, this one for the horned beasts, this one for the fishes. They do the same with all the beings of creation. And then the smoke contains all that which has been made sacred by the fire.

The pipe also represents the relationship between the people who are participating. The ceremony is a communal thing; it is one pipe that is passed to everyone. It speaks of who we are, in a sacred sense—that we are all relatives. It’s the idea of the joining of all peoples—which is certainly a very real kind of reconciliation, on a very high level.♦

—Joseph Epes Brown on the Native American symbol of relationship, PARABOLA, Winter 1989, “Triad.” This issue is available here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.

* The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk’s Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux, recorded and edited by Joseph Epes Brown. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953