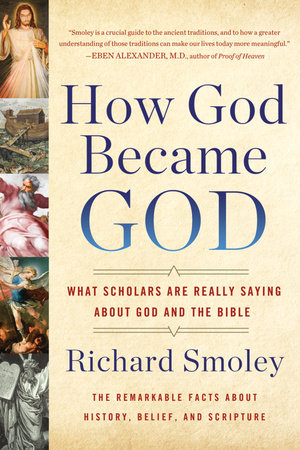

HOW GOD BECAME GOD: What Scholars are Really Saying About God And the Bible

HOW GOD BECAME GOD: What Scholars are Really Saying About God And the Bible

Richard Smoley. Tarcherperigree/Penguin.

2016. PP.320. $19 Paper

Reviewed by John Shirley

Well, then, here we are–and how do we make sense of our thrownness?

What is “thrownness”? Richard Smoley says it is the usual English translation of Heidegger’s Geworfenheit:

It means this: We have been thrown into this world without knowing why or how. As people sometimes say, “I didn’t ask to be born.” And you didn’t (at least as far as you can remember). But you are here, and you have to deal with it.

That passage is a representative sample of much of Smoley’s writing in How God Became God. It’s somewhere between the tone of a friendly public speaker and a deeply educated friend at a cafe table; it’s a congenial tête-à-tête with a man of knowledge who doesn’t speak down–he speaks directly to us, eye to eye, not afraid to gently contradict but always seeking a resonant universality. Along with his high-points hermeneutics of biblical scholarship, tracing a kind of arc through Old and New Testaments, , thrownness is a kind of universality-fulcrum for this work; it’s a touchstone most people can identify with on some level: the sense of being overwhelmed by the question of existence, the why of it, the mystery of the underlying meaning.

This may be a breakthrough work for Richard Smoley, a book many readers will likely find especially engaging and powerful for its readability and startling reveals. The author of such works as Inner Christianity: A Guide to the Esoteric Tradition, Conscious Love: Insights from Mystical Christianity, and The Dice Game of Shiva: How Consciousness Creates the Universe, Smoley is already noted for his ability to convey the cosmic and the complex, the arcane and its arcana, with straightforward clarity. In those books and others he explains what should be almost impossible to explain–yet he never dilutes the material to the point of over-simplifying blurriness. Flashes of insight and a feel for the human condition bring his exposition alive.

If anything, How God Became God, though taking on the daunting subject of the evolution of Western religion, is his most approachable book yet. It gives us a Richard Smoley taking another step closer to real intimacy with the reader. As if in a conversation, he anticipates the questions bound to pop into a reader’s mind:

Conventional Christianity teaches something that is explicitly denied in its own sacred scriptures.

How could this have happened?

Smoley does answer that question. When there’s a question he can’t fully satisfy, he tells us straight out that no one knows–and why that is.

While Smoley recognizes threads of historicity in portions of the Old Testament, he never hesitates to point up the prominence of legend in the Bible. Literal-mindedness doesn’t serve the seeker delving into the Pentateuch, certainly. But applying scholarly consensus and common sense, delving the known history of the Judaic peoples and their contiguous cultures, Smoley leads us through the wilderness of the Old Testament, and into the New; he interrogates the legend about Moses and our assumptions about Paul. He points out, with telling evidence, that most of the tale of Exodus could not have happened–though there may be some small kernel of history–and that archaeology has failed to find any proof of David and Solomon; that Jesus’ early followers did not believe he was divine; that the original biblical texts are lost, and what has come down to us is a bit of a shambles.

Smoley takes us back to what is known–sometimes what is inferred–about the roots of Judaism. He explains that Solomon’s Temple, if it existed, was far smaller than described in the Bible, as was the Davidian kingdom.

When Smoley brings the fuzzy origins of Yahweh, the Lord of Hosts, into better focus, we learn that originally Yahweh was probably not an overarching One God of all; he was not clearly a figure of monotheism. He seems to have started out as just another deity among many in the area, subordinate, in a set-up reminiscent of Gnosticism, to a higher God–El, or Elyon. Smoley offers examples, such as Deuteronomy 32:8-9, which, in the oldest available texts, suggests that Yahweh was given charge of a portion of the world by Elyon and “he fixed the boundaries…according to the number of the gods”: hence implying the existence of other gods, and apportioning to Yahweh an area for him to rule over as a local deity. Some theologians argue the text should read, instead, “the Most High,” appointing “the Sons of Israel” to certain nations. But Smoley’s interpretation leans toward a divine plurality, and a lower status initially for Yahweh, citing appearances by this being–in Genesis 18: 1-2, as one example–that make him appear to be more a mere angel than the great god of all. As Judaism evolves over time, Yahweh graduates to the Great Angel–a holy intermediary between humanity and the over-god. Still later, he’s made the High God. This step-by-step development makes more sense, given the polytheistic background of the region, than the sudden appearance of a lone lord of all creation.

Smoley thinks that around this time the tradition made a great mistake–an original sin, committed by religion itself. .

But when religion confuses its own inevitably limited picture of the transcendent Reality with Reality itself, it is making a mistake. It is a very dangerous one.

Why? Because the next step is to assume that your image of God is the only true one, and all others are therefore false. This was a mistake made by the faith of ancient Israel, says Smoley, and it was transmitted like a heritable disease to its offspring, Christianity and Islam.

Then…there’s Asherah. Who? How God Became God offers evidence, including inscriptions from the monarchical period, suggesting that Asherah was a goddess consort of Yahweh. In addition to other indications, Smoley references Margaret Baker’s argument that standard worship in the First Temple was devoted to a trinity of gods: El, Yahwh, and Asherah. (It seems almost a foreshadowing of Catholicism’s Holy Trinity.)

Smoley covers far more than this–and then plunges headlong into Christianity. Though Christian texts are not nearly so old as the Septuagint, they have their own issues with textual corruption. They also suffer from the probability of evangelical insertions–the Jesus Seminar and other scholarly sources assume that only a portion of statements attributed to Jesus were actually spoken by him.

Smoley is not the first to point out that biblical texts have been corrupted by dodgy translations, interpolations, and convenient revisionism, their literal believability marred by the failure of many prophesies. At least as far back as the early Christian sage Origen –see for example his third-century letter to Africanus–there was discussion of textual shenanigans, of missing passages and awkward variants among versions of sacred books. Albert Schweitzer’s critique of New Testament apocalyptic sayings has been around for a long time–Smoley discusses it–and there is a glib documentary claiming, quite unconvincingly, that Jesus never existed at all; Smoley effectively dismantles that allegation. More recently, Reza Aslan’s best-seller, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth claimed Jesus was in large part an illiterate political activist, a mere zealot revolutionary who was genuinely interested in overthrowing the Romans.

To some extent, the chapters of How God Became God dealing with Christianity could be considered a dual refutation; of literal-minded modern evangelical Christianity on the one hand, and of Reza Aslan’s popular Zealot on the other. He casts down on a number of Aslan’s basic assertions, and points out that nothing in the gospels hints that Jesus had a political agenda. Not only did he adjure people to “give to Caesar what is Caesar’s,” he repeatedly called his followers to turn to the spiritual, to turn their backs on the material reality of the time–with one exception: Jesus and his brother James the Just were quite insistent about caring for the poor.

Smoley states flatly, “The Gospels in the New Testament contain much material about Jesus that is not factually true.” But who, then, was Jesus? A former Essene, who made an enemy of the sect later? A mystic who is closer to the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas than the Gospel of John? The possibility apparently exists. Yet Smoley does not dismiss everything in the gospels; he even thinks it probable that Jesus believed he was indeed a descendent of David.

One of the more revealing chapters suggests that Paul–Saul of Tarsus–is, like Jesus, a victim of words being put in his mouth. Smoley offers good evidence that Paul believed not in a physical resurrection of Christians, but in the resurrection of a spiritual body. Paul may have been more an esoteric practitioner than what we currently think of as a conventional Christian. Smoley suggests, too, that Jesus’ Resurrection may have been more a spiritual manifestation than the physical one offered up by the gospels.

Smoley isn’t an apologist for Saul of Tarsus; he acknowledges Paul’s prejudices, his placing of men above women. But as Smoley says, “You can find Paul’s ideas inspiring and profound without believing…every last thing he said.”

The book explores metaphorical interpretations of Genesis–and Smoley engages in his own parables, which he returns to in his short, effective exegesis of practical mysticism. One of the unitive themes of How God Became God is Smoley’s metaphor of a “water table underlying everything we call reality,” a transcendent consciousness, a “living, vibrant, moving presence…”

The world of the five senses…is simply a crust that floats on this eternal presence.

Smoley identifies this presence with the Ground of Being, or Spirit. And, he tells us,

We can say that there are points in this crust of reality where the water of the Spirit breaks through…Those “wells,” shall we say, are moments of encounter with the Sacred.

Despite its many desert-like stretches of barbarism, its faulty transmission, its biases and flagrant myths, the Bible, Smoley demonstrates, seethes beneath the surface with sacred springs. ♦

John Shirley is the author of Gurdjieff: An Introduction to His Life and Ideas (Penguin/Tarcher), and novels such as Doyle After Death (HarperCollins/Witness) and The Other End.

From our current Summer Issue, Volume 41, No. 2: Innocence & Experience. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.