One day, as a small child, I was struck by the wonder of how amazing it is that we just show up in a particular body, with a head we can’t see, looking out into the world. I kept asking, “What is this all about?” I wondered if adults really knew something about how this all happened. To me, it seemed they were not concerned, as their replies were cursory: “God’s plan can’t be known. Don’t worry yourself over these things.” But I had to keep asking. I think all of us have the asking part of ourselves, even though it is masked by our daily difficulties and personal ambitions. Our spirit of inquiry is another name for the desire for truth. When we allow ourselves to open deeply to our spirit of inquiry, we find that the real motivating force in our lives is the infinite spirit we all are, beyond the limits of what we can imagine.

Through years of contemplative practice, our spirit of inquiry takes its twists and turns, but it always seems to come back to what the late great Zen master, Suzuki Roshi, once said: “The most important thing is to find out the most important thing.” For me, the most important thing is asking the question, “Who or what am I, really?” Is there an entity we can call me? What is this awareness that manifests the world, that manifests the idea of me? The ultimate question is to ask deeply, “What is it, really?” We step back from our intellect and our emotional attachments, and allow ourselves to come face to face with what, in Zen, is called our original face. Our original face is simply the totality of our being, right here and right now. It includes what we conceive of as outside of us as well as inside. It includes all of our sensory experience, including the thinking mind. Our original face is what is actually here. It is the living spirit we are, eluding all labels, including this one.

At the end of Huston Smith’s autobiography, Tales of Wonder, he describes an experience his friend Ann Jauregui had as a young girl in Michigan, a beautiful merging of the spirit of inquiry with spirit itself:

In summer she would lie on a wooden raft anchored in the bay, listening to the waters lapping, drowsy in the warm sunshine. The warm day, the clear northern light, and the water’s gentle motion together worked a semi-hypnotic effect. Then suddenly Ann would snap alert and feel intensely alive, or rather that everything was alive and that she was part of it. The rocks, the rowboats on the shore, the water itself—everything seemed pulsating with a kind of energy. She found she could put questions to the experience. “What is my role in all this?” she asked. “I want to know,” she whispered. “Show me.” The rocks, the trees, the water—all in silent chorus “answered”—not in words, of course—that her wanting to know, just that, was her part of the pulsating landscape. “Creation delights in the recognition of itself” is how she would later put it.

Even though almost all of us have had such transcendent or mystical experiences, most of us tend to forget them or not attach much importance to them. When I’ve discussed mine and other people’s similar experiences, I’ve found one common denominator. Our wanting to know is revealed as the intense aliveness of the experience itself. As our wanting to know intensifies, we become aware that the aliveness we bring to each moment is the true knowing.

This spirit of wanting to know is our deepest devotion to the mysterious presence of life itself. Underneath our drive to fulfill neurotic desire is the longing for wholeness, to become one with our true self.

As our wanting to know is revealed as the aliveness of spirit, devotion to our desire for truth is revealed as devotion to spirit itself. So inquiry and devotion arise together. Great Doubt, Great Faith. They further each other’s development. We cultivate devotion to spirit through inquiry. We cultivate inquiry into spirit through our devotion.

Thus our desire for truth moves beyond the confines of the conceptual realm. Thought has no power over the all-pervading presence that we are. Thinking can only manifest and dissolve as ever more thoughts arise. Thought cannot separate anything. And yet we continually believe that it can, when, for example, we cling to the thought that there is something wrong with our life. Real spiritual inquiry continually questions this assumption. No matter what we think is happening, what is happening is an expression of pure presence, and no division takes place. In the beginning stages of practice, we naturally embark on self-inquiry with our thinking mind. Questions help us let go of thought. Next we learn to ask the questions by merging with pure presence. We now ask questions from the very source of thought, and our desire for truth is revealed to be this pure presence.

As we become more aware, we realize how insubstantial thought is. We persevere in our spirit of inquiry into thought. To the extent that we can look at thought as an object of our awareness, we identify with awareness itself rather than with fleeting thought. We see how ephemeral thought is. There is space around our thinking. We are now free to decide: “Will I act upon my thought, or simply watch it dissipate?” This is how truth liberates thought from itself.

The Vedanta master Nisargadatta expressed the pure light of spirit with the following words:

There is in the body a current of energy, affection and intelligence, which guides, maintains and energizes the body. Discover that current, and hold onto it unswervingly. Be aware of the spark of life that weaves the tissues of your body and stay with it. It is the only reality that the body has. It is like looking at a burning incense stick; you see the stick and the smoke first; when you notice the fiery point, you realize it has the power to consume mountains of sticks and fill the universe with smoke. Timelessly the Self actualizes itself, without exhausting its infinite possibilities. In the incense stick simile, the stick is the body, and the smoke is the mind. As long as the mind is busy with its contortions, it does not perceive its source. The Guru comes and turns your attention to the spark within.

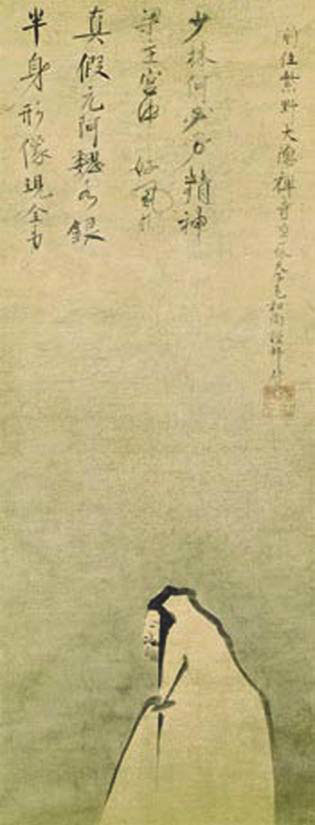

Keeping our attention on the aliveness within, the desire for truth continually confronts us with the mystery of existence itself. We’re confronted with the question: Is there really any outside or inside? The Zen poet, Ikkyū, wrote a poem, a wonderful portrayal of devotion to our spirit of inquiry in the face of the ultimate mystery:

Sick of what it is called

Sick of the names

I dedicate every pore

To what’s here

When we look for the substance of our being, we can say it is consciousness or awareness, but what is the real substance of that? Consciousness or awareness cannot be grasped by the thinking mind. If this is unfamiliar to you, try closing your eyes. Sit with the question of consciousness for a while. Now that you are temporarily removed from the concrete world of separate forms, what is actually here? When you open your eyes again, the world of forms reappears. What is present when our eyes are open and yet does not change when they are closed? Or what is here when we are asleep and dreaming, and is also present when we are in the waking state? When we allow ourselves to become fully absorbed in these questions, they can be a powerful tool. These questions help us to realize our actual being in the world, that this actual being is the source of the world itself. Yet the thinking mind is unable to understand why this is true. Is there actually any separation between what we are, and what the world is?

We divide our experience among the five senses and sometimes add thinking as the sixth sense. Although we can distinguish them one from another, talk about them, and understand what we say, how do talk and understanding help us pinpoint their actual substance? When we try to grasp the concrete substance of hearing, feeling, seeing, tasting, smelling, or thinking, what we sense is merely the raw experience. Substance has no name, just as reality itself or the presence that is reading these words, has no name.

Before we create any mental divisions, this no-name realization is one road to the mystery. The substance of our experience is saturated with the substance of this presence that is now looking out from our eyes. If we do not know what the substance is, we do not know what the experience is. Realizing this can free us to be more fully intimate with our experience, without the confinement of conceptual knowledge about it. It is the mind only that creates the idea of some division between inside and outside, substance and no substance. This mystery manifests in all the dimensions of being, but cannot be limited by or found in any of them.

This awareness is truth, but it is truth beyond all concepts of true or false. It is what we are, and we are the absence of any story. No matter what we imagine to be happening, what is happening is, in fact, just this mysterious being that gives birth to everything.

Divine spirit may be committed to our oneness with itself, but it has no commitment to our story turning out the way we want it to. So if we are serious about committing to the spiritual path, we need to let go of our attachment to our own stories. This includes the story of our path to awakening, or even the story of letting go of our story! These subtle tales can be tricky in their persistence. So we need be vigilant. We need to observe the ones that can actually masquerade as selfless behavior.

![Oxherding Picture #9 "Returning to the Source" by Tenshō Shūbun [died c. 1444]. Original traditionally attributed to Twelfth Century Chinese Zen Master Kakuans](https://parabola.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Oxherding-Picture-9-Returning-to-the-Source-by-Tenshō-Shūbun-died-c.-1444.-Original-traditionally-attributed-to-Twelfth-Century-Chinese-Zen-Master-Kakuans.jpg)

When we deeply ask, “What or who am I?” we allow ourselves to become what Zen master Hakuin called “The Great Doubt:” “At the bottom of great doubt lies great awakening. If you doubt fully, you will awaken fully.”

The Zen Masters teach us that the fully awakened mind is always already fully present in its entirety, with nothing lacking. When I first started practicing Zen, this statement became the object of my own great doubt. My questioning brought me face to face, again and again, with the reality that my thinking mind did not, could not, fully believe what Hakuin said. Gradually it became clear that there was no way to do away with the doubt. Great doubt is one expression of what we are. It became clear to me that to ask deeply the question of “Who am I?” was to allow myself to become the doubt itself.

After many years of practice, I had a sudden revelation. Subtly, I had thought all along I was doubting Buddha nature, doubting enlightenment itself. But when I finally left my awareness to itself, including all my ideas about it, I realized what is actually here and now cannot be doubted! All this time, I had been doubting the truth of my ideas about reality. There is no truth to be found in the concept of enlightenment, Buddha Nature or God. So it is imperative to doubt the truth of our concepts about God, and at the same time to be aware that we are doubting. Reality is not an it that can be doubted or affirmed. Reality cannot be grasped by making it into an object of thought. But we have to try. Indeed, our desire for truth is deepened by our trying. It is deepened by our wanting to know. This is our role: not to know what reality is. Here and now is the source. Open your arms. Drink in this moment. Here and now is one hundred percent identical with every possible manifestation in the whole universe. If you doubt this idea deeply, you will awaken deeply.

![No Spiritual Meaning, Calligraphy by Musō Soseki [1275-1351], Japanese Zen Master and Poet](https://parabola.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/No-Spirtual-Meaning.jpg)

Recently, I was walking by a stream in the country. The sparkling water, its peaceful sound, and the beautiful nearby field with cows grazing, inspired me to merge with it all. Just as in Ann Jauregui’s story, I wanted to know my role in this, and I wanted to feel needed and loved by the whole of reality. It was as if everything was calling out to me that my role was to want to know, and that wanting to know includes wanting to be needed and loved. If we’re willing to yield to the spirit of inquiry, our longing will lead us to see that we’ve always been needed and loved.

We fully acknowledge our need. Then we inquire, “What is this need, really?” If we’re willing to yield to it, where will it lead us? When we deeply realize the oneness of all creation, when the rose and the compost shine with the same luminous light of true nature, we may then realize, as the contemporary spiritual teacher Adyashanti has said, that we are what we want and we want what we are. Earth is an expression of our true mother, the bountiful mother of all creation. When we are willing to receive her fully, she will dissolve all of our desires and fears. Here’s a beautiful poem by Thich Nhat Hanh, expressing Mother Earth’s patient waiting for us:

The Earth Is Waiting For You

The Earth is always patient and

open-hearted.

She is waiting for you.

She has been waiting for you for the

last trillion lifetimes.

She can wait for any length of time.

She knows you will come back to her one day.

Fresh and green, she will welcome you

exactly like the first time, because love

never says “This is the last time,”

because Earth is a loving mother.

She will never stop waiting for you.*♦

*Thich Nhat Hanh, Reprinted with permission from The Long Road Turn To Joy: A Guide to Walking Meditation (Parallax Press, Berkeley, California, 1996), (www.parallax.org).

From Parabola, Volume 35, Number 3: “Desire,” Fall 2010. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing.