A Report on the 2015 Parliament of the World’s Religions

It was a pilgrimage of reparation, undertaken by a few people who shouldered the burden of an act that had shaken the entire world. As Be’sha Blondin, an elder of the Sahtu Got’ine Dene people of the Northwest Territories, described it at the 2015 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Salt Lake City, the people of this remote Arctic village had long believed that the early deaths of so many men in the tribe had been caused by the uranium they had hauled on their backs in the 1940s from the mine on their native land to barges that shipped it south. But they were horrified when they learned fifty years later that this ore had supplied much of the material for the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Determined to make amends to the Japanese people, a delegation of six Dene traveled to Hiroshima in 1998 on the fifty-third anniversary of the nuclear explosion.

This is an example of how one small group of people set about “Reclaiming the Heart of Humanity,” the theme of the 2015 Parliament, held at the Salt Lake City convention center October 15–19, 2015. It is a story about awakening to the ways in which the past casts a pall on the present, about assuming responsibility for suffering that one might not personally have been guilty of causing but in which one feels inescapably implicated, and it is about consciously, bravely, and ceremonially inviting a new relationship with another. It is one example of inspirited action among the many that were explored throughout these five days not only in panel discussions, workshops, and speeches but also, and perhaps most significantly, through countless informal and spontaneous encounters among participants. Attracting an estimated 9,500 people from more than seventy countries and representing fifty different faiths and ten times that many sub-faiths, the event provided a field on which activism could merge with mysticism, curiosity about beliefs other than one’s own could transcend dogma, and compassion could overcome stale preconceptions. It invited all of us participants to sample paths that are vital to others in order to discover solace, inspiration, and meaning for ourselves.

The first Parliament of the World’s Religions was held in Chicago in 1893. On that occasion Universalist Antoinette Brown Blackwell, widely recognized as the first American woman to be ordained as a minister and known for her impassioned style of preaching, thundered to fellow attendees: “Women are needed in the pulpit as imperatively and for the same reason that they are needed in the world—because they are women. Women have become—or when the ingrained habit of unconscious imitation has been superseded, they will become—indispensable to the religious evolution of the human race.” Although the Salt Lake City Parliament was the fifth to be held since then, it was the first in which Blackwell’s vision would be realized: this time women’s issues and women presenters were at the forefront. Bringing about this shift was the resolute work of the Women’s Task Force, led by Parliament trustee Phyllis Curott, which made it possible for the entire first day of the gathering to be devoted to an Inaugural Women’s Assembly. “Women and girls have been excluded from religious leadership, been subjected to sanctioned female genital mutilation, and victimized by sacred texts that have been misinterpreted to keep them from making decisions about their own bodies and from having a voice,” said Curott at the opening plenary. How women have both contributed to and been denied authority in the world’s faith traditions was a topic that unfolded through a range of notable speakers that day, including Hindu activist Vandana Shiva, who insisted we have a duty to disobey an unjust law, because we all have a higher obligation to the “law of Mother Earth”; author, naturalist, and self-proclaimed “radical environmentalist” Terry Tempest Williams, who risked standing on the ground of the Mormon faith she was born in to call for diversity in religion; religious scholar Charlene Spretnak; Jungian Jean Shinoda Bolen; and Maori elder Dr. Rangimarie Turuki Arikirangi Rose Pere, who invited all of us to stand and offer a greeting from her tradition by placing a hand on a neighbor’s shoulder and pressing our foreheads together.

After a full day of such empowering speeches, the official Parliament opened that evening with a procession into the auditorium led by Native Americans whose ancestral lands cover the territory that is now Utah. Their drumbeats and colorful banners brought the audience to their feet and even onto their chairs, clapping and ready to further celebrate the vitality and relevance of spirituality to all people. Instead, the house lights dimmed, the drumbeats faded to canned music, a lectern was carried onstage, and nine men in suits took their places in chairs before the audience. “Where are the women?” one female voice shouted out from the vast, darkened room. Although Parliament Chair Imam Abdul Malik Mujahid assured her—and all those inwardly asking the same question—that more than fifty percent of the presenters at this Parliament were women, it was impossible not to see the choice of those considered worthy of launching this important international gathering as indicative of the problem so many voices had expounded on during the previous hours.

Starting the following morning, each day at the Parliament began at 7:00 A.M. with a variety of worship sessions that participants could attend. These included Tai Chi, a multi-faith meditation on caring for creation, a Zoroastrian thanksgiving ceremony, Hebrew chanting of the Hadrat Kodesh for the healing of the planet, a Jain puja, and many more. Windowless convention center rooms furnished with nothing more distinctive than rows of folding chairs were transformed into places of worship. At a service of Gospel music from Salt Lake City’s Calvary Baptist Church, for example, Catholic nuns and a Buddhist monk in saffron robes, along with dozens of others in less religiously specific clothing, did their best to match the jubilant spirit of the mostly African-American choir in offering up songs of praise to the Christian Lord. The opportunity not just to witness the faith service of another but actually to participate along with other welcome strangers was a consistently heartwarming part of the Parliament agenda.

Throughout the day, with just enough time allotted for people to rush from one room of the enormous convention center to another, a plethora of ninety-minute breakout sessions was available; typically forty programs were on the roster in most time slots. The result was a somewhat overwhelming choice of speeches, panel discussions, workshops, films, musical performances, and ceremonies. Since many sessions featured two presenters speaking on sometimes marginally related topics, people tried to match their attendance to the one they wanted to hear, and since the sessions frequently ran late, causing others to start late, a hubbub of opening and closing doors and people in motion often made the meeting rooms feel like way stations. Nevertheless, there was more than enough to interest every seeker: discussions of potential partnerships between science and religion; workshops on the contemporary practice of paganism; explorations into how different faith traditions are meeting the challenges of global warming, poverty, and social injustice; and ongoing inquiries into the theme of women in religion, such as Jan Peppler’s session on biblical texts that seem to urge women to endure abuse. Comparing attitudes of submission that women have been forced to bear with Job’s ultimate surrender to God, Peppler explained, “Women have thought they needed to be selfless, faithful, loving. God, to Job, is like a batterer. Finally Job responds like an abused woman: You’re right, what do I know?” In a shared session I myself described the practice of making simple gifts of beauty to broken places as a path to spiritual ecology. Then Karenna Gore, Director of the Center for Earth Ethics at Union Theological Seminary, along with Navajo Lyla June Johnston and Mayan Geraldine Patrick Encina, created a women’s initiation ceremony for four participants.

The breakout sessions offered guidance both for developing inner qualities, as in a workshop led by a Jewish rabbi and a Buddhist minister on working with traditional wisdom sources to promote peace, and for bringing the work of religion out of the sanctuary and into the street, as in a session by leaders of different faiths on the steps they’re taking to improve sanitation and hygiene in their communities. There were even a few sessions designed to help religious groups use technology and digital tools to convey their messages, run petitions, and mobilize followers, skills ISIS has mastered to an alarmingly successful degree. That terrorist organization, which Muslim leaders all over the world have condemned as heretical, was the topic at several Parliament sessions. As one speaker expressed it at a panel called “Street Theology of Anger: A Critical Analysis of ISIS and The Lord’s Resistance Army,” Islamophobia has become the newest form of “sanctified hatred.” Tariq Ramadan, Professor of Contemporary Islamic Studies at Oxford University, urged everyone to wage a different kind of jihad, or holy war: “Jihad is a noble term,” he said. “We need a jihad against poverty, a jihad against violence to women, a jihad against racism.”

Upon registration at the Parliament every attendee received not only the hefty book containing information about all the programs and presenters but also a booklet featuring the organization’s Declaration toward a Global Ethic. First issued at the 1993 Parliament and articulating essential values shared by virtually all religions and spiritual traditions, the declaration opens with this bold statement: “The world is in agony.” Citing abuse of the Earth’s ecosystems, poverty, hunger, and economic disparity, violence and “in particular … aggression and hatred in the name of religion,” the Declaration models a determination not to turn away from the harsh realities confronting so many communities, and hence so many faith traditions, in the world today. This imperative for religion to focus not just on the ineffable and transcendent, but on bringing spiritual practices and outlooks to a world in crisis, was evident each evening when the thousands of attendees came together for plenary sessions devoted to different topics. “Where are your wounds?” demanded Allan Boesak, a South African cleric from the Dutch Reformed Church, at the plenary on War, Violence, and Hate Speech. “And if you have no wounds, then was there nothing worth fighting for?”

At the Climate Change plenary, indigenous speakers like Chief Arvol Lookinghorse, spiritual leader of the Sioux, reminded the audience that caring for creation has always been an intrinsic part of indigenous spiritual and cultural traditions, while members of other faiths implored congregations to put more emphasis on environmental sustainability as a religious concern. Brian D. McLaren, Christian activist and author of Naked Spirituality, urged us to rethink our relationship to our shared home: “Brothers and sisters, the Earth is crying to us. We need religion as never before to come together in saving love to avert climate disaster on this beautiful, precious, resilient planet.” Especially inspiring was the plenary devoted to Emerging Leaders, for it brought onstage young people of different cultures and faith traditions, all speaking with clarity and conviction about how they are working to right injustice to people and other living beings. Zach Hunter talked about Loose Change to Loosen Chains, a student-led organization he founded when he was in seventh grade to collect spare change for organizations actively working to end slavery around the world. Fourteen-year-old Ta’Kaiya Blaney of the Sliammon First Nation in Canada became an outspoken environmental activist at age ten when she learned that otters would be endangered by a massive pipeline proposed for transporting Alberta tar sands to British Columbia. She concluded her speech by describing society as “a back-and-forth event between vision and impossibility” and admitting that she is excited about the future.

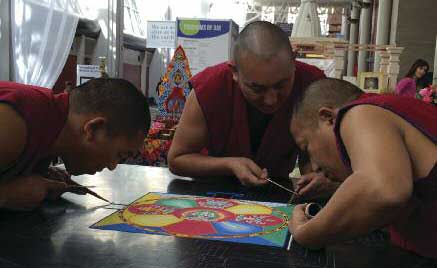

The pursuit of what it means to reclaim the heart of humanity continued beyond the meeting rooms, the tables set with microphones and glasses of water, the amplified, simulcast speeches before thousands. Parliament organizers took advantage of the layout of the convention center, which features a variety of open hub-like spaces, to bring people together with events and displays. In the main lobby Tibetan Buddhist monks bent for hours each day over the table on which they were creating an intricate sand mandala, while just a few feet away was a booth where participants could choose a colored ribbon on which to write a message for delegates at the upcoming climate change talks in Paris. On Sunday morning representatives of six different world religions joined them there to teach attendees simple prayers from their traditions, each with accompanying gestures. On another level of the convention center, the Life Story Library invited anyone who cared to do so to tell a story about a pivotal moment in his or her life. Each story was videotaped and will become part of the foundation’s vast collection. In a courtyard outside the building a sacred fire tended by Native Americans burned continually throughout the event, and firekeepers provided participants with pinches of tobacco with which to make prayers. Certainly the most popular offering during the Parliament was the daily langar, a delicious vegetarian lunch offered free to all by the Sikh community. Every day thousands of diners removed their shoes and donned simple white cotton head coverings before sitting on the floor and sharing a meal. In the end, the 2015 Parliament was an event that by its very nature brought about the theme it proposed.

What does it mean to reclaim the heart of humanity? It might happen, as in Be’Sha Blondin’s story, with a delegation from one nation making formal amends to people from another nation or it might happen spontaneously between two individuals on a city street. One evening, walking back to the convention center after dinner in a neighborhood restaurant, I passed a disheveled, unshaven man in a dirty, oversized coat sitting on the curb in front of a parking lot. On the sidewalk beside him squatted a woman in a clean, well-pressed skirt and jacket, her Parliament name tag dangling from a cord around her neck. She had placed one hand on the man’s arm and was looking with care and concern into his face as he stared blankly toward the street in front of them. What was transpiring between this man and woman, how either might be affected afterwards, could not, of course, be known. But what was evident was that one human had seen the despair of another and had called a halt to her own agenda in order to reach out. This is the way to reclaim the heart of humanity: to push beyond the limitations of tolerance and cultivate compassion, to say yes to the invitations the world is constantly offering to step off the familiar path and venture where we’re called, and to risk giving of ourselves even if we’re not sure what that might entail or what the outcome may be.

Although it took a hundred years for the second Parliament of the World’s Religions to follow the first, and successive gatherings have occurred only every five or six years, Parliament leaders have determined that the world needs to meet together more frequently to keep the conversations, lessons, and longing for connection going. The next gathering is scheduled for 2017. We all have plenty to do to get ready.♦

1 Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography.

2 Parliaments have been held in Chicago in 1993, Cape Town in 1999, Barcelona in 2004, and Melbourne in 2009. For a report on the Melbourne Parliament see Trebbe Johnson, “World Religions Get Down to Earth: A Report from the 2009 Parliament of the World’s Religions,” Parabola, Vol. 35, No. 2, Summer 2010, 90–105.