As the following passage begins, Jesus of Nazareth, here called Yeshua, is suffering on the cross, attended by several including his mother, Mary, here known as Maryam, and Elizabeth, cousin to Maryam and mother of John the Baptist. It is Elizabeth who narrates.

—The Editors

The cross, or whatever other heavy burden the hero carries, is himself, or rather the Self, his wholeness which is both God and animal … the totality of his Being, which is rooted in his animal nature and reaches out beyond the merely human towards the divine. His wholeness implies a tremendous tension of opposites paradoxically at one with themselves, as in the Cross, their most perfect symbol.

—C.G. Jung

“For it is right to mount upon the Cross of Christ, who is the Word stretched out … of whom the spirit saith: For what else is Christ but the Word, the sound of God? So that the Word is the upright beam whereon I am crucified. And the sound is that which crosseth it, the nature of man. And the nail which holdeth the crosstree unto the upright in the midst thereof is the metanoia, the turning around of men.” —Acts of Peter, Apocryphal New Testament

It was a long way from Joseph’s quiet house with its flower-filled courtyards to the hellish Golgotha, and I have always been ashamed of my relief that by the time we reached the ghastly place, Yeshua, His kittel still seamless but in tatters and bloody, had already been raised up, nailed to that cruelty, the cross, and that He was all the time coming and going in and out of consciousness.

Maryam let out one sound, an echo of the animal noises women make while giving birth, but without faltering in her steps she moved to the foot of the cross, ignoring the rather weak attempt of the Roman centurion guarding it to stop her. For it was clear it was she who was in command and that nothing—no-one—was going to stop her from being as close to her son as she could be.

I followed her with Maryam of Magdala, and we stationed ourselves one at each side with Martha and her sister close behind. The disciples and Eleazer were gathered at the other side of the cross.

I confess it took me some time to find the courage to look up, look at Him, but I heard Him murmur, “Beloved Mother….”

Why is Martha fidgeting? I thought. Surely she can see this is not a moment for activity, but I do her wrong: she was preparing in a little phial some myrrh which is close to the poppy in its ability to relieve pain and to distance the sufferer from it. She poured it onto a little sponge and bravely stepped forward and asked the centurion to put it on the end of his sword and offer it to Yeshua, which he did. But Yeshua feebly turned His head away. He would not take it. The centurion shrugged, but seemed disappointed. And Martha made a sound of angry distress.

We were far from alone up there on that hill. A huge crowd was still gathering as word must have got around that they were crucifying this “King.” Hideous the way they stared; the relish at another’s anguish, and yet I must be fair for there were others who soon turned away repulsed, disgusted and left; others who prayed; others who wept. But then someone called out: “Go on, King! Why don’t you call on Elijah to come and save you?” “Yes!” other voices joined in. “Where is your father now?”

It was then I became aware of Maryam’s intense state: We seemed to be contained within a circle she was making, within which her atmosphere was charging itself with love, and that Yeshua, and all of us—even that kindly centurion—all of us were contained in an ever-increasing vibration coming from her, entirely focused on her son.

Each time He came back into consciousness she held His eye with hers.

And then I saw that she was trying to draw off from her son the dark cloud of fear, the sharp shards of pain. She was sending towards Him her own light.

And then I saw that I was not alone in perceiving her intention: all the others were seeing it too.

Together we began to work with her towards this. The intention became visible in the form of light, a palpable substance, yet so fragile it could be broken by the touch of one fingertip—(I swear the centurion felt it too). Rays of light were emanating towards Him from the entire circle—the ones coming from His mother were the most visible, and never wavered in their strength. The others came and went as we all strove not be overwhelmed by grief and terror.

And then He spoke: Father, forgive them for they know not what they do … and fainted away again.

It was the longest of all mornings, the longest of all days.

Hour after hour we stood there, hour after hour we tried to watch faithfully, tried to sustain our efforts to be with Him. Hour after hour, he seemed on the point of leaving us—forever, as we thought then. Hour after hour He returned from wherever He had gone when another wave of agony swept over Him to hard to bear.

Once He lifted His head with very great difficulty and said, “Eleazer, from this day my mother is your mother,” and after a long while turned it towards Maryam and said, “Mother, from this day Eleazer is your son….”

Eleazer, weeping, said, “Rabbi … Rabbi….”

Dry-eyed, Maryam nodded slightly, completely focused on her intention, not prepared to allow it to weaken, as if she was carrying precious water in her hands and none must be spilled.

And then came a terrible moment.

Suddenly Yeshua opened His eyes wide, turned upwards to the skies, so that we could see the whites of them,

as if He was already more than halfway to death.

But no, He called out in the language of his childhood, and in a voice of such despair I pray daily for it to be erased from my memory….

“Eli, eli, lama sabachtani?” which means, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

My heart began to beat rapidly. And my own despair began to set in. So, He, even He cannot after all transcend physical suffering, death.

But before the thought had time to lodge fixedly Maryam’s voice rang out: “For he hath not despised nor abhorred the affliction of the afflicted; neither hath he hid his face from him; but when he cried unto him, he heard….”

And I recognized the words they had both been speaking: they came from one of King David’s psalms.

And I saw that Yeshua drew strength from them.

He seemed to surrender any remaining tension against all the pain of body and mind, and said simply in an almost child-like voice, “I am thirsty.”

Immediately the centurion fetched water from a pitcher and offered some to Yeshua on Martha’s sponge. And this time Yeshua sucked the sponge dry.

How much longer His agony continued after that I cannot tell, for on that day minutes became hours, hours became years.

But within those minutes which became hours; those hours which became days at last we heard Him sigh: “Now it is fulfilled….”

And I swear I saw His life force vanish upwards through the body and leave through the topmost part of His head….

Was it then that we were all held there outside time?

Was it then that I heard Him? Or did I dream this? Did we all dream the cross into a tree greening with leaves, sprouting with blossoms scenting the air?

Did we dream the voice? Did we dream Yeshua’s voice and what we heard Him say?

“To all of you who love me I say: I have leaped and you have leaped with me. I am on the cross, yet I am not on the cross, but on this immortal tree, which is life. See! It stands in the middle of heaven and earth … firm support of the universe, link between all things, a cosmic network, containing itself in all the medley of human nature. See! It is fixed by the invisible nails of the spirit … I touch heaven with the top of my head, I strengthen the earth with my feet and in the middle ground I embrace the whole atmosphere with my immeasurable hands….”

Dream, vision, as swiftly as it had come, as swiftly it vanished and we were absorbed once more into the reality in front of us.

At the awful sound of the men’s sobs as they struggled to remove the nails, Maryam fainted against me. The two of us began to fall slowly to the ground, and certainly would have fallen had it not been for the ready arms of the other women.

The centurion came rushing with his pitcher of water and helped us to seat her against a rock.

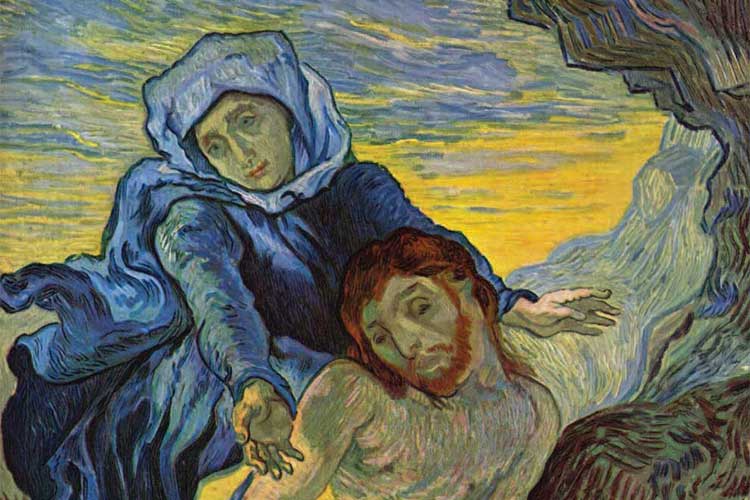

By the time the disciples had lifted Yeshua down from the cross, Maryam had come to herself and was trying to rise and go to Him. But she could not and sat back against the rock, holding her arms out to Him like a mother asking the midwife to lay her child in her eager arms.

So they brought Him to her, and laid Him across her knees. She cradled His head in her arms and began very carefully to lift the thorn crown off and to wipe the blood away with her cloak, washing the wounded forehead with her tears. For suddenly and at last Maryam was weeping.

“My babe, my child, my rabbi,” she said again and again. “My babe, my child, my rabbi….”

Then, looking up blindly, “Where to lay Him? Where to lay Him?”

“Do not fret yourself,” said Martha in her sensible way. “That good man, Joseph, has thought of everything. See! He comes now with Pilate’s permission to bury Him now, before Sabbath begins—and in the tomb he had prepared for himself…. Now, you come way home with us, dear mother, and leave the men to do what must be done.”

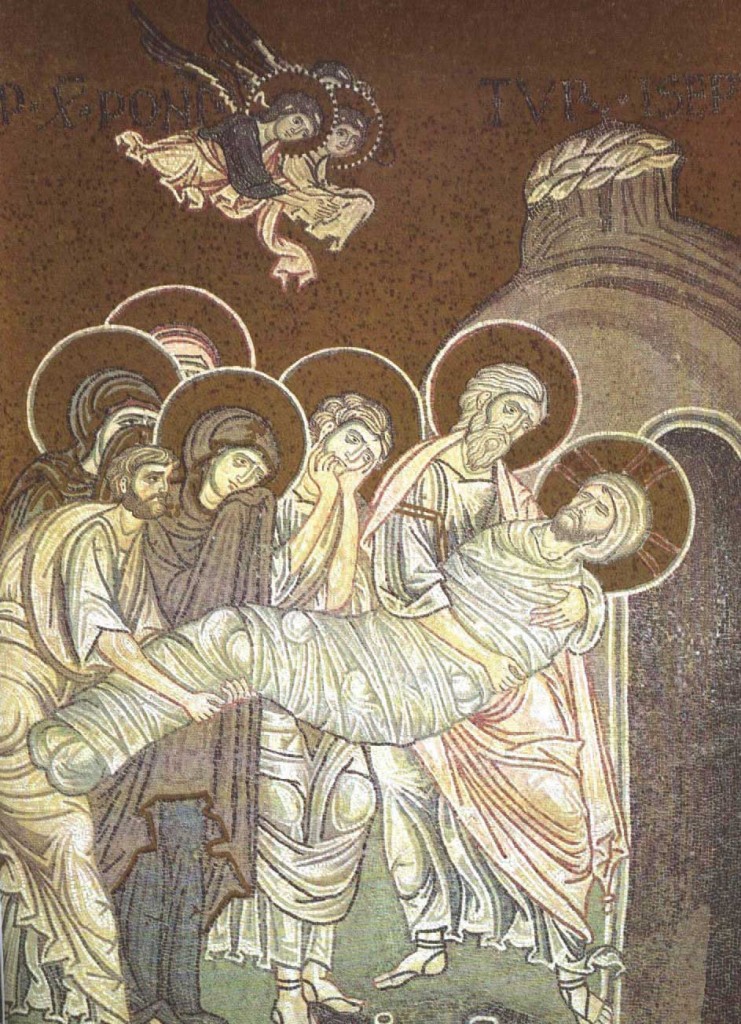

Obediently, Maryam allowed the men—Thomas, Simon, Eleazer and Jochanan—to lift Yeshua up and prepare to carry Him away.

Obediently she allowed us to help her to her feet.

Then we stood back and waited, trying so hard not to weep aloud as she kissed Yeshua’s brow, His hands, His feet. Although His eyes were already closed she made to close them with the soft palm of her hand.

“Thank you,” she whispered. “Thank you.” But only she knew who she was thanking: Joseph for giving his tomb? The men for carrying Him away to be bathed, anointed and robed in a shroud? Or was it Yeshua she was thanking? Or the Whole on High itself?

“Ave Maria, gratia plena …”

I led her home on the donkey Joseph had thought to find for her.

I led her home, and suddenly I was back on the road into Egypt all those years ago, riding beside and sometimes, when the path was narrow, behind her. Then we held our babes close to us, beloved burdens. Now here we were—two old, childless women, carrying emptiness, loss, heavy, heavy loss under our hearts.

I led her home, while Martha and the other women hurried on ahead to light the Sabbath candles.

I have never forgotten the bearing of Maryam as she stepped down from that donkey at the door of that house in Bethanehyeh, which had been Yeshua’s true home, heart and center of His teaching.

Somewhere during our long, slow journey she had shed all vestige of her human nature and crystallized into that of the mother of all. She even seemed to have grown in stature, resembling more the form of her mother, who had always seemed slightly larger than life—as a goddess might in barely veiled disguise. She seemed filled again with an immense gravity. Even her beauty had in some way taken on a new depth: the eyes larger than ever, full of a new kind of love which embraced us all as we gathered round her. Her sadness which showed in them now encompassed all suffering and immense compassion. The sweet curve of her lips remained, but there was a firmness there made up of courage and resolve. Her back was straight again, her shoulders no longer hunched up in that posture we all make when we cringe against pain.

No, she stood here as Our Lady, Our Lady of Mercy, of Forgiveness, of Hope, of Grace, the Shekinah herself of our time, as Sarah had been of hers and those other mothers, Rebekah, Rachel, Leah, preparing their hearths for the Sabbath….

“This Sabbath,” she said to us, “must be purer and more wholehearted than ever before.

“Let the candles glow as if we had indeed lit them from the Divine Sparks.

“And let the door be opened wider than ever!”

And so it was.

But that night, that first night, it was my turn to take her into my bed; my turn to hold her, to warm her, to love her through her weeping, silent or loud.

She was up before sunrise and discovered all the disciples asleep on the floor, having found their way to Bethanehyeh, drawn there some time during the night, as if they knew it was the only place to be. She called us all together to watch the first rays spread up the sky.

And after the morning blessings had been said, the prayers recited, and bread broken and shared between us, she spoke to us.

“Sabbath is the holy space between the old and the new,” she began. “Sabbath until now has been the holy space between the week which has passed and the new one to come. But this Sabbath day is also the holy space between the end of my son’s life and a new beginning, where we must try to put into practice what He taught us—and He taught us enough and more for several lifetimes! This Sabbath we must together strike the first note of this new beginning. We have all engraved in our hearts, impressed upon our minds and in our very marrowbone the four things He taught us: ecstasy, service, humility, intention. And now is the time to activate intention as never before. So now, when we pray, truly wishing to direct our intention, we imagine that we are light and that everything around us is light, light from every direction and from every side. If we turn to the right we find shining light, and if we turn to the left we will find light and above us the crown of light which crowns the desires of the thoughts. This light is unfathomable, and from it comes grace and benevolence….”

And so, due to her strength and presence we celebrated a vibrant Sabbath….♦

Reprinted by permission from Jenny Koralek’s Cosmic Mysteries: A Fable (Toward Publishing, 2015)