“There is a story that tells of Meister Eckhart’s meeting with a poor man: “You may be holy,” says Eckhart, “but what made you holy, brother?” And the answer comes: “My sitting still, my elevated thoughts, and my union with God.” It is useful for our present theme to note that the practice of sitting still is given pride of place.

In the Middle Ages people were well aware of the inexhaustible power that arises simply from sitting still. After that time, knowledge of the purifying power of stillness and its practice was, in the West, largely lost. The tradition of preparing man for the breakthrough of transcendence by means of inner quiet and motionless sitting has been preserved in the East to the present day. Even in cases where practice is apparently directed not to immobility but towards activity–as in archery, sword fighting, wrestling, painting, flower arrangement–it is always the inner attitude of quiet and not the successful performance of the ways which is regarded as of fundamental importance.

Once a technique has been mastered, any inadequate performance is mirrored in wrong attitudes. The traditional knowledge of the fact that it is possible for a man to be inwardly cleansed solely through the practice of right posture has kept alive the significance of correct sitting. The inner quiet which arises when the body is motionless and in its best possible form can become the source of transcendental experience. By emptying ourselves of all those matters that normally occupy us we become receptive to Greater Being.

It should be understood that the transformation which is brought about by means of meditation is not merely a change in man’s inner life, but a renewal of his whole person. It is a mistake to imagine that enlightenment is no more than an experience which suddenly brings fresh inward understanding, as a brilliant physicist may have a sudden inspiration which throws new light on his work and causes a re-ordering of his whole system of thought.

Such an experience leaves the person himself unchanged. True enlightenment has nothing to do with this kind of sudden insight. When it occurs, it has the effect of so fundamentally affecting and shaking the whole person that he himself, as well as his total physical existence in the world, is completely transformed.

To what extent the habit of sitting can impress and change us becomes clear only when we have taken pains to practice it. After a short time we find ourselves asking: how is it possible that such a simple exercise can have such far-reaching effects on the body and soul? Sitting still, we begin to realize, is not what we had imagined physical or spiritual practice to be. We are faced, therefore, with the question: “What is it we are really practicing if, although both are affected it is neither body nor spirit?” The answer to this is that the person who practices is himself being practiced. The one who is worked upon is the Person in his original totality, who is present beneath and beyond all possible differentiation into the many and various physical, spiritual, and mental aspects. In so far as we regard and value ourselves as incarnate persons, certain manifestations in our life move from their accustomed shadow into the light of understanding. Thus our moods and postures take on new meaning. So long as we think of body and soul as two separate entities, we regard moods simply as “feelings,” and look upon bodily attitudes and breathing as merely physical manifestations. When, however, the whole person is recognized as a “thou,” it is no longer possible to separate body and soul. Once it becomes a question of transformation, our basic moods, together with all the gestures and postures that express them, acquire new significance. They are the means through which we grow aware of, manifest ourselves, and become physically present in the world…

The so-called “peace” of the world-ego, illustrated by the bourgeois aim of a “quiet life,” comes about when all inner movement and growth have stopped. Of quite a different quality is the peace of inner being and the life which strives to manifest itself through it. This kind of peace can only prevail where nothing further interrupts the movement towards becoming. To achieve such an attitude to life is the aim of all practice and meditation; it can never represent a state of “having arrived” but is always a process of “being on the way.” Such practice, therefore, is by no means acceptable to all. There are many who throng to the so-called prophets who promise a cheap kind of peace to troubled mankind. But such “masters” simply betray man by hiding from him the real cause of his anxiety, which lies in the desire for transformation inherent in his innermost being.” ♦

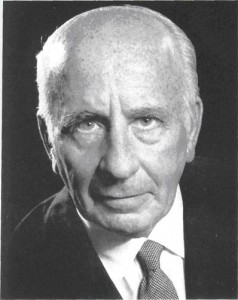

—From Karlfried Graf Dürckheim, Daily Life as Spiritual Exercise: The Way of Transformation, translated by Ruth Lewinnek and P.L. Travers (London: Allen & Unwin, 1971), pp.51-54, 58.

This excerpt appeared in our Fall 1996 issue, “Peace.” This issue is available here.